Twenty-four million years ago, in what is now Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, a volcanic crater lake quietly held the remains of plants and animals that fell into its waters. Over time, layer upon layer of sediment preserved them with extraordinary detail, creating a fossil treasure chest that scientists are only now beginning to unlock. Among the discoveries recently made at this site, known as the Enspel Fossil-Lagerstätte, are fossilized linden blossoms and fossilized bumble bees—still bearing traces of pollen that tell a story older than human civilization itself.

This remarkable finding, led by researchers from the Department of Botany and Biodiversity Research at the University of Vienna, does more than add to the catalog of ancient life. It connects the deep past to the present, showing that bumble bees were already devoted pollinators of linden trees millions of years ago, just as they remain today. In a time when pollinators face a global crisis, these fossils are not only scientific marvels but also poignant reminders of nature’s long and fragile history.

Fossils That Speak of Relationships

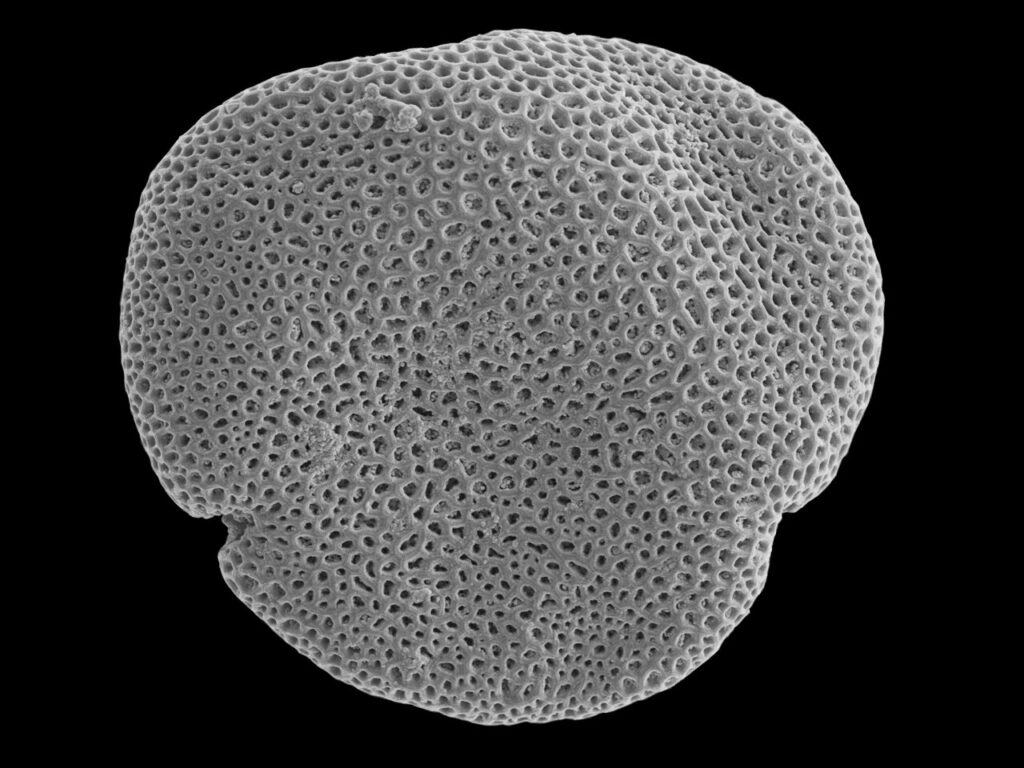

The true wonder of this discovery lies not simply in the preservation of plants and insects, but in the evidence of their interaction. The fossilized bumble bees were found with pollen grains still attached to their hairs, while fossilized blossoms revealed traces of the same pollen. These tiny grains—silent witnesses across geological time—demonstrate a partnership that has endured for millions of years: the mutual relationship between bees and linden trees.

The research team used innovative methods to reveal this hidden story. Under UV and blue light, the microscopic pollen grains glowed faintly, allowing scientists to extract them with a needle finer than a hair. After cleaning and analyzing them with advanced microscopes, the researchers could match the pollen to specific flowers, linking insect and plant directly for the first time in the fossil record.

Naming New Species from the Past

From this investigation emerged three entirely new species. The linden blossoms were named Tilia magnasepala, “the linden tree with large sepals,” their ancient beauty immortalized in stone. Two new bumble bee species were also identified: Bombus (Kronobombus) messegus and Bombus (Timebombus) paleocrater. Their names honor both their age and the unique volcanic landscape where they were found.

These bees rank among the oldest known members of their genus. Only one fossil species, found in Colorado, is older. To find them together with the flowers they pollinated is unprecedented. Never before has a fossil flower and its pollinating insect been described from the same sediments and linked so directly by the presence of pollen.

Why Linden Trees and Bees Matter

Today, linden trees—sometimes called lime or basswood—remain important nectar sources for bees across Europe and beyond. Their blossoms perfume the air in midsummer, offering a banquet of pollen and nectar. That bees were visiting linden trees twenty-four million years ago shows that this ecological partnership is ancient, stable, and remarkably enduring.

But it also raises urgent questions. If bees and linden trees have thrived together for millions of years, what does it mean that pollinators are now declining so rapidly in just a few human generations? Wild bees, bumble bees, and countless other insects are under threat from habitat loss, pesticides, climate change, and disease. The fossil record reveals resilience, but it also reminds us that ecosystems are vulnerable to disruption.

Lessons from the Deep Past

By studying ancient ecosystems, scientists can better understand how plants and animals responded to past climate changes, extinctions, and evolutionary pressures. The Enspel fossils provide a rare glimpse into pollinator behavior: the bumble bees of that time displayed “flower constancy,” meaning they focused on one type of flower per foraging flight. This same behavior is vital today, ensuring efficient pollination and reproductive success for many plants.

Such insights underscore the delicate interdependence of life. Pollinators are not interchangeable machines; they form finely tuned relationships with plants. Disrupting these relationships risks unraveling entire ecosystems. Fossils remind us that these connections are not new—they are ancient, deeply woven into the fabric of life on Earth.

A Story of Continuity and Fragility

There is something deeply moving about a fossilized bee carrying pollen to its watery grave. It never knew that its last flight would be preserved for eternity, that millions of years later humans would uncover its story. And yet, its quiet act of pollination has become a message across time: a reminder that the natural bonds we see today are not fleeting but are rooted in deep evolutionary history.

Still, history also carries warnings. Past ecosystems rose and fell with climate shifts, extinctions, and environmental upheavals. The continuity of linden and bee interactions across millions of years highlights both the resilience of life and the fragility of balance. What has survived eons could still be lost within a century if current threats to pollinators are not addressed.

Looking Forward by Looking Back

The discovery at Enspel is more than a scientific milestone. It is a story that connects past and present, science and society. By uncovering fossilized blossoms and bees, researchers have illuminated not only the ancient roots of pollination but also the importance of protecting it today.

The tiny fossil grains of pollen preserved in stone whisper to us across time: bees and trees have been partners far longer than humans have walked the Earth. To let that partnership falter now would not only diminish our world—it would break a chain of life millions of years in the making.

The lesson is clear. If we wish to safeguard the future of our ecosystems, we must honor and protect the ancient relationships that sustain them. The fossil bees of Enspel remind us that every flight of a bee, every blossom it visits, is part of a story that stretches across deep time—a story that now depends on us to continue.

More information: 24 million years of pollination interaction between European linden flowers and bumble bees., New Phytologist (2025). DOI: 10.1111/nph.70531. nph.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/nph.70531