For centuries, scientists have puzzled over the question of when humans first made their way to the vast, mysterious landmass of Sahul, which now includes Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania. It’s a question that brings together archaeology, genetics, and a sense of wonder about humanity’s early migrations. Now, thanks to a groundbreaking study, the debate is taking a new turn, suggesting that our ancient ancestors arrived in Sahul around 60,000 years ago.

Theories about when humans first entered this land have long diverged, with two dominant schools of thought emerging over time. The “short chronology” theory argues that humans entered Sahul as recently as 47,000 to 51,000 years ago, supported by a variety of genetic studies. On the other hand, the “long chronology” theory proposes an earlier arrival, around 60,000 years ago or more. This new research, published in Science Advances, provides compelling evidence in favor of the long chronology theory, shifting the balance of the debate.

Unlocking the Mystery of Ancient Migrations

Understanding the timeline of human migration into Sahul has always been challenging, especially since physical evidence from the region is scarce. Archaeological sites are few and far between, and those that do exist often provide limited insight into the dates of early human settlements. In light of this, researchers have turned to genetic data, which offers a different and powerful lens through which to explore ancient human movement.

The study focused on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), the genetic material passed down through mothers, as well as Y-chromosome data, which traces paternal lineage. These genetic markers have long been used to map human migration patterns. By analyzing the genetic diversity of 2,456 mitochondrial genomes from Indigenous populations across Australia, New Guinea, and Oceania, the researchers aimed to pinpoint the likely time of divergence between ancient human groups in Southeast Asia and their descendants in Sahul.

The methodology used was based on a technique known as the “molecular clock,” which measures the rate of genetic mutations over time. By counting the number of mutations in specific genetic markers, scientists can estimate when two populations diverged from a common ancestor. This method is especially useful in the absence of clear archaeological evidence and has helped to offer a clearer picture of early human migration.

The Power of Molecular Clocks

The researchers discovered that, by using molecular clock techniques, the data supported a timeline consistent with the long chronology theory. While other studies using different methods had suggested a more recent migration, the team argues that these estimates were based on assumptions that may have minimized the true age of the migration. The study’s authors contend that, when alternative assumptions and methods are applied, the genetic evidence places the arrival of humans in Sahul around 60,000 years ago, far earlier than the short chronology would suggest.

“We believe that other assumptions and methodologies, even when applied to the Fu method, push the estimates into the long chronology range,” the authors explain, referring to a specific calculation method for estimating genetic divergence. The team’s findings align with earlier archaeological evidence, which has pointed to human settlements in Sahul that date back to around 53,000 to 60,000 years ago. In fact, two key archaeological sites, Nauwalabila I in the Northern Territory and Madjedbebe in northern Australia, show evidence of human occupation that aligns with the long chronology theory.

Two Paths Into Sahul

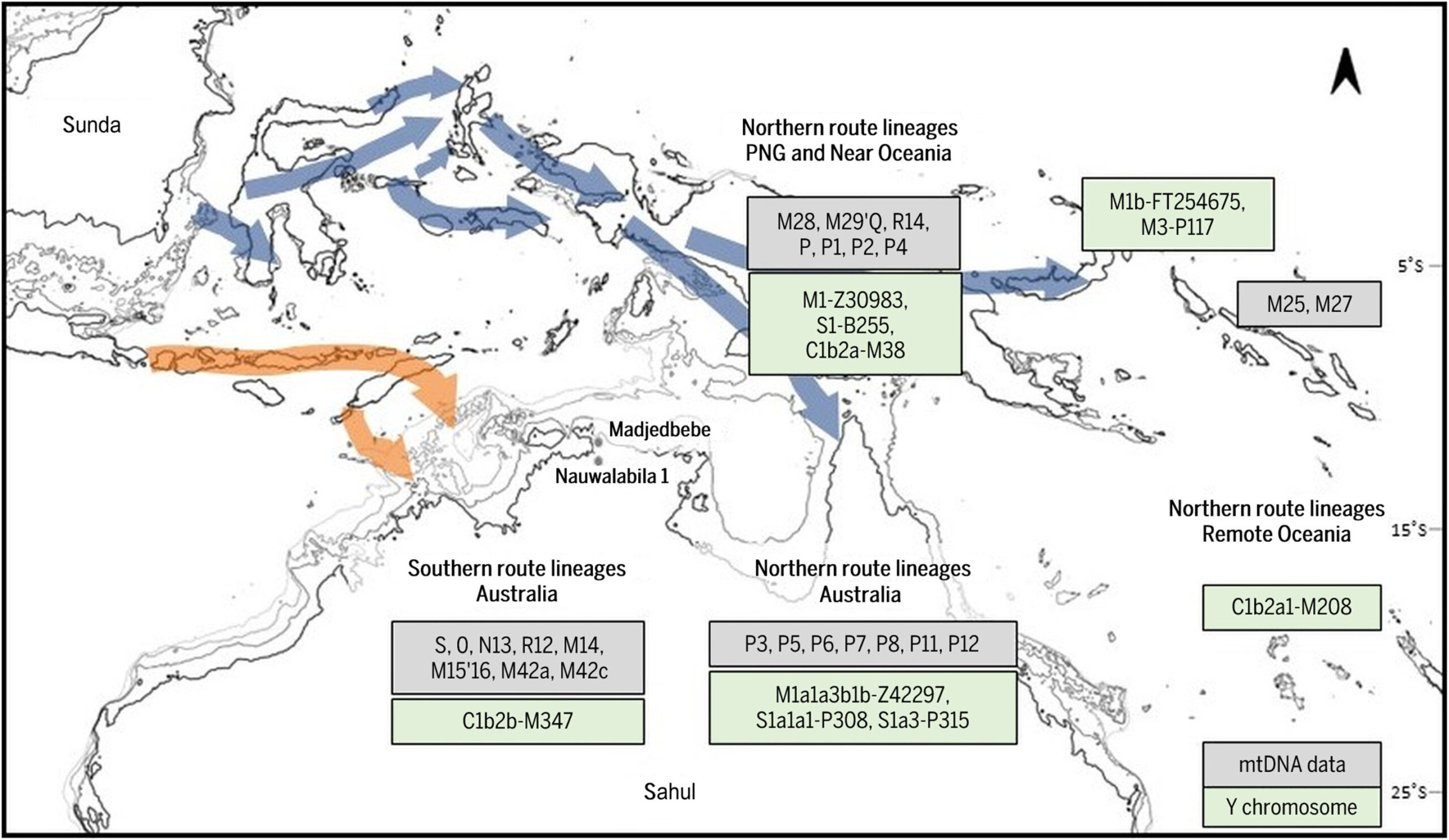

One of the most intriguing aspects of the study was the discovery of two distinct genetic groups, both originating from Southeast Asia. These groups, the study suggests, likely took separate routes into Sahul. One group moved northward into New Guinea, while the other took a southern route into what is now Australia. Both groups, the authors propose, shared a common ancestry that traces back to the ancient landmass of Sundaland, which is now submerged beneath the seas of Southeast Asia.

This split at the very moment humans first set foot in Sahul suggests that early human migration was more complex than previously thought. Rather than a single migration wave, these two distinct populations seem to have arrived via different paths—one through the north and the other through the south. “The mitogenome evidence shifts the balance toward the likelihood of at least two distinct dispersal routes into Sahul,” the authors write, “both northern and southern, with a common ancestry in Sundaland.”

While it’s impossible to pinpoint the exact landing sites of these ancient migrants, the researchers suggest that the Bird’s Head peninsula in West New Guinea and the northwest Sahul shelf were likely points of entry into the region. These areas would have been exposed as islands during the last glacial maximum, allowing early humans to reach them.

The Surprising Evidence of Seafaring

Perhaps the most surprising revelation from this study is the evidence suggesting that these early humans were capable of seafaring. To reach their new homes, they would have had to cross stretches of water up to 100 kilometers wide—an impressive feat for a time when modern boats and navigation tools were still millennia away. This discovery paints a picture of early humans as not just wanderers on land but also skilled navigators, capable of charting their course across open water.

The study’s findings, therefore, suggest that human migration into Sahul was not only earlier than previously thought but also more sophisticated. These ancient peoples were not simply walking across land bridges—they were crossing bodies of water, using boats or rafts to reach new lands. This discovery challenges earlier notions of early human migration, which often assumed that prehistoric people were land-bound and incapable of crossing wide expanses of water.

Why This Research Matters

The significance of this research cannot be overstated. It not only sheds light on the timing and routes of one of the most important human migrations in prehistory, but it also challenges our understanding of early human capabilities. The ability to navigate the seas more than 60,000 years ago suggests a level of sophistication and ingenuity that we often associate with much later human civilizations.

This study also offers crucial insights into the heritage and origins of the Indigenous peoples of Australia and New Guinea. By tracing their genetic lineage back to these ancient migrations, the research adds depth to our understanding of their connection to the land and the enduring cultural legacy that has shaped these regions for tens of thousands of years.

As we continue to explore the depths of human history, studies like this help to fill in the gaps, offering new perspectives on how our ancestors adapted to and thrived in a world that was both challenging and full of opportunity. The journey of humanity into Sahul is not just a story of survival—it is a story of discovery, resilience, and the spirit of exploration that continues to define us today.

More information: Francesca Gandini et al, Genomic evidence supports the “long chronology” for the peopling of Sahul, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ady9493