In the blistering heat of the Ethiopian desert, on the morning of November 24, 1974, a team of paleoanthropologists stumbled upon a fragment of bone sticking out of the ochre soil. It was not the first fossil they had found in this parched corner of the world, but it would prove to be the most famous. That bone—light, ancient, unmistakably hominin—was part of a skeleton that would soon be named Lucy.

As the researchers, led by Donald Johanson, sat around their campfire that evening, they played a Beatles cassette tape—specifically the song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” And so, a 3.2-million-year-old hominin came to be known not by a scientific code, but by a name that felt almost tender, almost familiar.

But Lucy was no ordinary fossil. She would rewrite chapters of the human story, challenge our understanding of what it means to walk upright, and open a window into a time when the Earth was wild, warm, and teeming with evolutionary possibility.

The Discovery That Danced with the Past

Lucy’s discovery site, the Hadar region in Ethiopia’s Afar Triangle, lies in what was once a lush floodplain. Millions of years ago, rivers meandered through grasslands, nourishing life in forms now long vanished. The sediment layers, like geological diary pages, preserve a tale of shifting climates, vanished volcanoes, and branching evolutionary trees.

As Johanson surveyed the area, he found a fragment of an elbow joint, remarkably small and ancient in appearance. Over the next few days, the team uncovered hundreds of pieces—skull fragments, ribs, a pelvis, a femur, and more. Astonishingly, nearly 40 percent of a single hominin skeleton emerged from the earth, a completeness unheard of in the field of paleoanthropology.

The skeleton belonged to a female, about 3 feet 6 inches tall and weighing around 60 pounds. Her small stature belied the enormous importance of what she represented. For the first time, scientists had in their hands a nearly complete look at a bipedal ancestor, frozen in time just as our lineage began to diverge from the great apes.

Standing Tall in a World of Giants

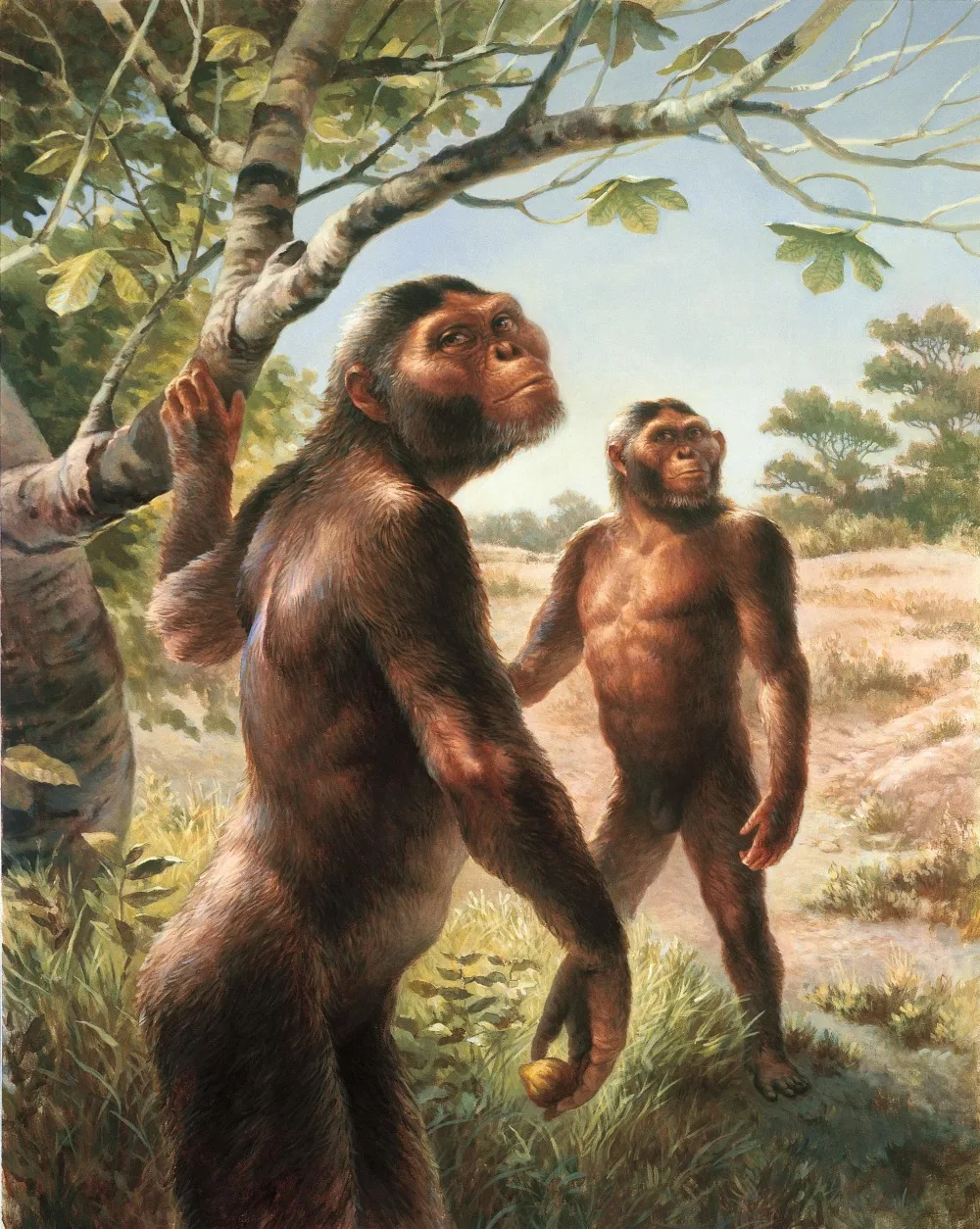

Australopithecus afarensis, Lucy’s species, lived between 3.9 and 2.9 million years ago, straddling the line between ape and human. Her brain was small—about 375 to 500 cubic centimeters, roughly the size of a chimpanzee’s—but her anatomy told a far more complex story.

Her pelvis was broad and bowl-shaped, like that of a modern human, and her thigh bone angled inward, aligning her knees under her center of gravity. These traits signaled an upright posture—a revolutionary adaptation. Lucy walked on two legs, not just occasionally, but habitually.

Yet her arms were long and curved, her shoulder sockets high—suggesting she still spent much of her time in trees. Lucy was a creature of two worlds: earthbound but not entirely grounded, adapted for walking yet still at home among the branches.

In this duality, Lucy bore witness to a critical stage of human evolution. She was not a perfect prototype but a mosaic of past and future—a snapshot of evolution in motion.

A Face Without a Voice

We may never know the exact contours of Lucy’s face, the color of her skin, or the sound of her voice. She left behind no tools, no fire pits, no burials or art. Her kind lived in a time before symbols, before language as we know it. And yet her bones speak eloquently of survival.

Lucy’s jaw jutted forward. Her canines were smaller than those of a chimpanzee, but still more pronounced than ours. Her hands had dexterity, but not precision. She may have plucked fruit, scavenged meat, or even cracked nuts with stones, though no tools were found directly associated with her remains.

She was likely part of a social group, navigating the dangers of predators, droughts, and rival species. Her environment was unforgiving—home to saber-toothed cats, massive crocodiles, and hyenas with bone-crushing jaws. Life for Lucy was a daily negotiation between nourishment and risk.

We don’t know how she died, though her skeleton shows signs of possible trauma. Some scientists speculate she may have fallen from a tree, others suggest disease or predation. But death, for Lucy, was not an end—it was a revelation. In her stillness, she became a voice for the countless early hominins whose stories would otherwise be lost.

More Than a Missing Link

For decades, the term “missing link” has haunted evolutionary science, suggesting there is a neat, linear ladder from ape to human. But Lucy upended that simplistic notion. She showed that evolution is not a straight line but a sprawling, tangled bush of experimentation.

Australopithecus afarensis was not necessarily a direct ancestor of Homo sapiens, but part of a larger genus that gave rise to later species, including Homo habilis and eventually Homo erectus. Lucy’s species walked the earth for nearly a million years, adapting to changes in climate and landscape, long before our genus took its first breath.

What made Lucy so significant was not that she was the first to walk upright—but that her remains offered the clearest evidence yet of bipedalism in a hominin that still bore many apelike traits. She stood at the crossroads of evolutionary pressure and adaptation, balancing on two feet while the rest of her body reached for the trees.

Her discovery answered old questions—and raised new ones. Why did bipedalism evolve when the brain had not yet enlarged? What environmental pressures made walking more advantageous than climbing? What did the landscape look like that shaped such a creature?

Ethiopia’s Gift to Humanity

Lucy’s name became shorthand for deep ancestry, a talisman of human origin stories. After her excavation, the fossils were taken to the National Museum in Addis Ababa, where she became both a scientific treasure and a national icon.

Ethiopians take pride in being the cradle of humanity—a title earned through countless discoveries in the Afar and Omo valleys. Lucy symbolized not just a species, but a heritage shared by all people, regardless of race or nationality. In her ancient silence, she spoke of unity.

Her international fame led to heated debates about where fossils should be stored and who “owns” ancient human remains. Some argued for her remains to be repatriated when traveling for exhibits, fearing damage or loss. Others saw her as a messenger—a fragile ambassador of deep time meant to be shared with the world.

In 2007, Lucy went on tour in the United States, prompting both excitement and controversy. While millions flocked to see her, some researchers criticized the risk involved in moving such priceless relics. Through it all, Lucy remained dignified in her silence, her bones echoing across millennia.

Dancing with the DNA of Ancestors

For decades, we relied on morphology—bones and teeth—to reconstruct the lives of our ancestors. But the rise of ancient DNA analysis has added new dimensions to the story. While DNA degrades quickly in hot climates and has never been recovered from Lucy herself, later hominin fossils have yielded genetic secrets that reshape our understanding of the human family tree.

Today, we know that Homo sapiens interbred with Neanderthals and Denisovans. We know that migration patterns were far more complex than previously thought. While Lucy lived too long ago to leave genetic traces we can recover, she remains a reference point—a baseline in our evolutionary clock.

As we unravel the double helix of our past, Lucy’s story becomes more poignant. She is the reminder that long before our species emerged, there were others—upright, social, intelligent in their own way—navigating the same world we now claim as ours.

The Spirit of a Species

There is something uncanny about Lucy. To see her reconstructed in museums, with eyes that peer back at us through silicone and resin, is to confront ourselves. Not just our biology, but our vulnerability.

She had no language, but she lived in community. She had no fire, but she survived. She made no tools, but she walked—on feet shaped by evolution to support a destiny she could never imagine. In every footprint she left behind, in every glance at the sky through ancient branches, she was preparing the way for us.

She is not merely a specimen. She is a symbol. A reminder that our humanity did not begin with writing or cities or even fire—but with the courage to stand, to balance, to reach.

In the Footsteps of Lucy

In 1978, just a few years after Lucy’s discovery, another landmark event occurred: the unearthing of fossilized footprints at Laetoli in Tanzania. These prints, preserved in volcanic ash, were made by a hominin walking upright over 3.6 million years ago—possibly a relative of Lucy’s species.

To see those prints, side by side, is to feel a chill of connection. They are small, close together, pressed into ancient earth by beings who lived, breathed, feared, and hoped. Just like us.

The Laetoli footprints confirm what Lucy suggested: that long before we were “human” in the modern sense, we walked. We claimed the land, step by deliberate step. We stood, even when our brains were small and our tools few.

That act—of rising upright—is not merely anatomical. It is metaphorical. It is the first chapter in the long journey of becoming.

A Legacy Carved in Stone

Lucy’s legacy is not frozen in fossilized bone, nor confined to museum glass. It lives in the questions she provokes, the debates she inspires, and the wonder she awakens. She is at the heart of our fascination with beginnings—who we were, and who we might yet become.

She also reminds us of the fragility of discovery. Her skeleton might easily have eroded into dust, lost to wind and time. But instead, she endured. Through chance, geology, and human curiosity, she rose from the earth once more.

And what she tells us is both humbling and empowering: that we come from survivors. From beings who adapted not because they were the strongest or smartest, but because they changed. Because they stood and walked forward.

The Whisper of Ancients

To think of Lucy is to think of the vastness of time, and yet also its intimacy. She lived over three million years ago, yet we know her name. We know how she moved. We can imagine her gazing across the grasslands, wary of rustling brush, seeking safety in her group.

Her species is long gone. But the echoes remain—in our gait, in our bones, in our dreams of flight and discovery. Every step we take is one she made possible.

As science continues to dig into the earth, decoding the past with ever finer tools, we must never lose sight of what makes Lucy matter: not just the science, but the soul. The recognition that in those ancient bones lies the first note of a symphony we are still composing.

Lucy was not the end. She was the beginning. And in her bones, the Earth remembers.