Deep in the rugged landscapes of Boodjamulla National Park in northwestern Queensland, a fossil has been uncovered that whispers of an ancient world. The discovery is not of a towering dinosaur or a fearsome predator, but of a bird—large, grounded, and long vanished. This bird, named Menura tyawanoides, is now recognized as an ancestor of one of Australia’s most captivating creatures: the lyrebird.

The find, dating back an astonishing 17 to 18 million years, is far more than a fragment of bone. It is a story frozen in stone, a reminder of how deep the roots of Australia’s songbirds truly reach.

From Echoes of the Past to Modern Mimicry

Modern lyrebirds are celebrated for their astonishing talent: the ability to mimic almost any sound they hear. From chainsaws and car alarms to the songs of other birds, their repertoire is a living orchestra of the forest. But while their vocal brilliance is legendary, the fossil wrist bone of Menura tyawanoides reveals a different tale.

Unlike its modern descendants, this prehistoric bird was largely earthbound. Its wrist structure suggests it had only limited flying ability, relying instead on life within the dense understory of ancient tropical rainforests. Where today’s lyrebirds dance and display in the open, Menura tyawanoides would have lived hidden beneath the towering canopies of Miocene forests, its wings less useful than its legs for navigating the shadows of its world.

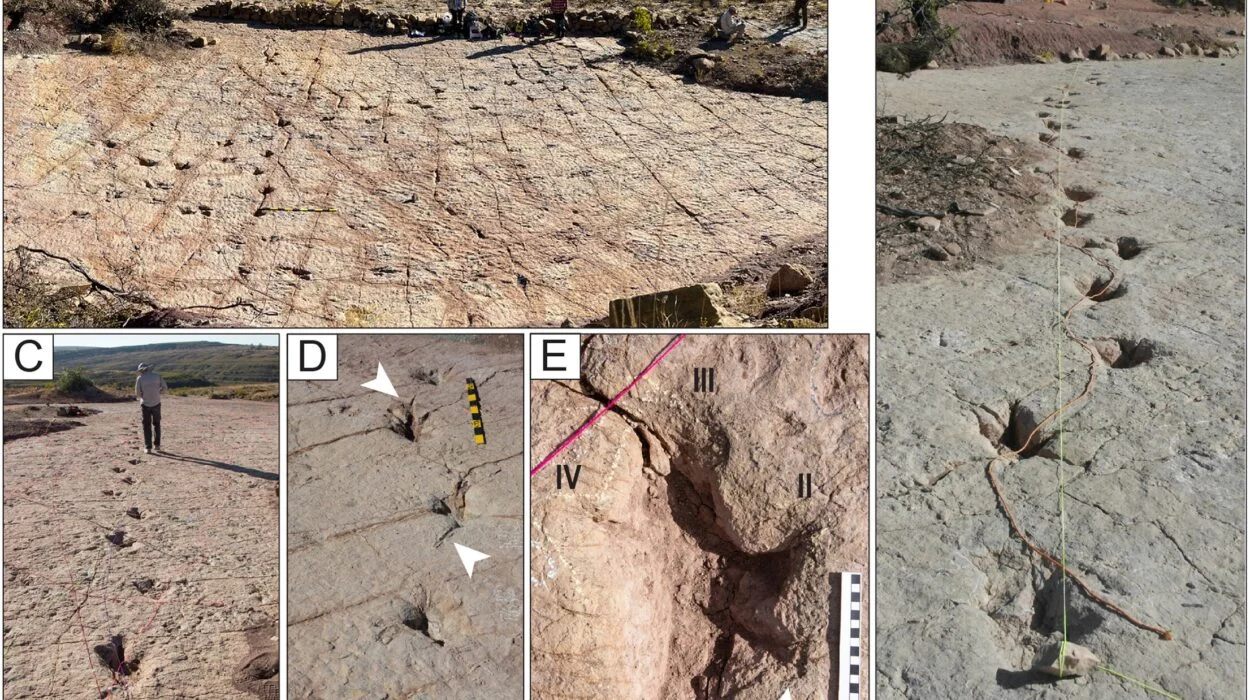

A Treasure from Riversleigh’s Fossil Wonderland

The discovery was made in Riversleigh, a fossil-rich site within Boodjamulla National Park that has been called one of the four most significant fossil localities on Earth. This remarkable region has yielded hundreds of extinct species, from strange marsupials to long-lost reptiles and birds. Each fossil reveals not just an individual creature but a fragment of ancient ecosystems that once thrived under very different climates.

Professor Mike Archer of the University of New South Wales highlights the broader importance of finds like Menura tyawanoides. Riversleigh, he explains, holds a record of survival and adaptation. Ancient species once faced powerful climate shifts, and while many perished, others endured and evolved. In today’s world, where ecosystems are again under pressure from climate change, these fossilized lessons become crucial guides for understanding resilience and extinction.

The Songlines of Evolution

What makes the story of Menura tyawanoides so extraordinary is its connection to the lyrebird, one of Australia’s most iconic songbirds. To imagine that the complex mimicry of the modern lyrebird may trace back to a grounded rainforest ancestor is to glimpse the continuity of life across vast stretches of time.

This lineage suggests that even as climates shifted and landscapes transformed, the genetic and behavioral threads of the lyrebird survived. Today’s birds, with their elaborate vocal displays, are not just entertainers of the forest—they are living heirs to a story millions of years in the making.

Lessons for Today and Tomorrow

The discovery of Menura tyawanoides is not simply about filling gaps in evolutionary history. It also carries a warning and a hope. Australia’s ecosystems have always been shaped by change, from the ancient rainforests of the Miocene to today’s drier landscapes. The fossil record shows that survival often depends on adaptability, resilience, and the preservation of critical habitats.

As modern lyrebirds face threats from deforestation, climate change, and habitat fragmentation, the story of their ancient ancestor reminds us that extinction is not inevitable. With knowledge, conservation, and care, species can endure, as their ancestors once did through turbulent ages.

A Window into Deep Time

Standing in Boodjamulla National Park today, surrounded by the ochre cliffs and emerald waters, it is difficult to imagine the lush tropical forests that once carpeted this land. Yet beneath the ground lie the fossils that bring those worlds back to life. The wrist bone of Menura tyawanoides is small, but its meaning is vast.

It tells us that Australia’s songbirds have ancient origins, that their stories are written in both stone and song, and that the echoes of the past continue to resonate in the voices of living creatures. The discovery is more than paleontology—it is a reminder of the unbroken thread that ties us to the deep time of Earth, and of the responsibility we share in ensuring that thread does not break.