For decades, the story of human evolution was told as though Neanderthals and Homo sapiens were separate chapters in the same book—different species that crossed paths late in prehistory, long before the Neanderthals disappeared. But a new international study led by researchers at Tel Aviv University and the French National Center for Scientific Research has revealed something far more profound.

In a cave on Mount Carmel, in northern Israel, a small fossil of a child has given us the earliest physical evidence that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens were not just neighbors, but companions, partners, and even family. The child, only about five years old when they died, lived roughly 140,000 years ago—long before the recognized period of gene exchange between the two groups. This ancient skeleton shows a mosaic of features belonging to both human types, making it the first-known evidence of interbreeding in the world.

The discovery, published in the journal L’Anthropologie, challenges the way we understand human evolution and the deep roots of our shared ancestry.

The Child of Skhul Cave

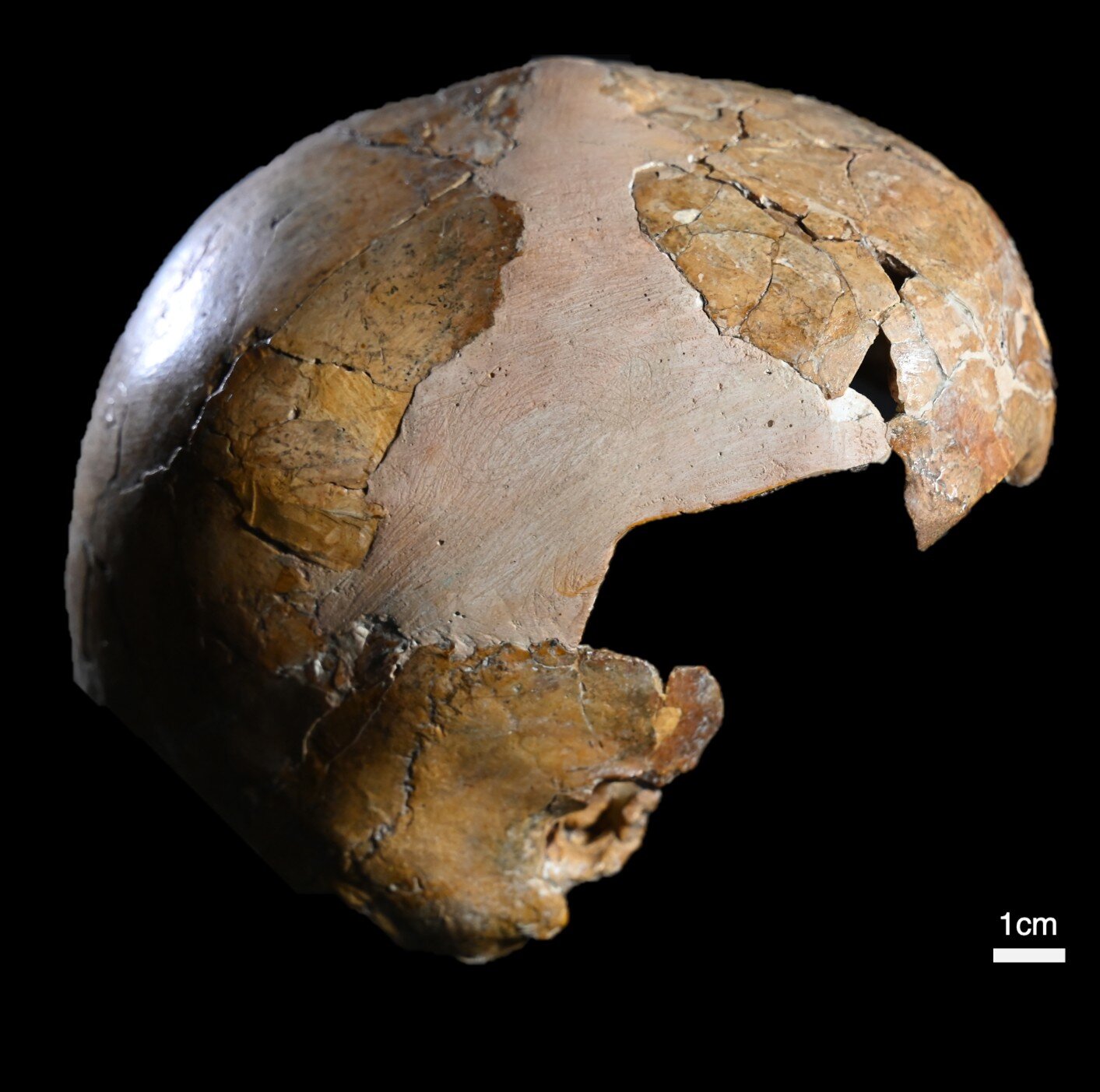

The fossil in question was unearthed nearly 90 years ago in the Skhul Cave on Mount Carmel, one of a series of caves rich in human history. For decades, scientists classified it as early Homo sapiens, part of a population that had left Africa and settled in the Levant. But new technologies have allowed researchers to revisit this child’s remains with fresh eyes and sharper tools.

Using micro-CT scanning at the Shmunis Family Anthropology Institute at Tel Aviv University, the team created a highly detailed three-dimensional model of the skull and jaw. This allowed them to study not only the visible bones but also hidden structures such as the inner ear and the network of blood vessels around the brain. What they found was astonishing.

The shape of the skull and its curvature resembled Homo sapiens, but the inner ear, the lower jaw, and the blood vessel system were distinctively Neanderthal. This unique combination could not be explained by simple variation—it pointed instead to direct biological and social relations between the two groups.

Neanderthals in the Land of Israel

For years, anthropologists believed that Neanderthals evolved in Europe and only arrived in the Levant region around 70,000 years ago. But recent discoveries have changed that narrative. In 2021, the same research team revealed fossils from the Nesher Ramla site in central Israel, showing that early Neanderthal populations had lived in the region as early as 400,000 years ago.

These local Neanderthals—dubbed Nesher Ramla Homo—shared the land with early groups of Homo sapiens who had begun migrating out of Africa roughly 200,000 years ago. The Levant, a geographical crossroads between Africa, Europe, and Asia, became a meeting ground where these populations encountered one another, exchanged ideas, and, as the new evidence shows, interbred.

The Skhul child embodies this encounter, serving as living proof that human history is not one of isolation, but of contact and blending.

A Bridge Across Populations

The implications of this discovery stretch far beyond one fossil. For decades, genetic studies have shown that modern humans carry traces of Neanderthal DNA—anywhere between 2% and 6% of our genome. These exchanges, however, were thought to have happened much later, between 60,000 and 40,000 years ago, after Homo sapiens had expanded across Eurasia.

But the Skhul child pushes this timeline back by nearly 100,000 years. This is not just evidence of distant genetic mixing—it is a snapshot of social relations tens of thousands of years earlier than expected.

“The fossil we studied is the earliest known physical evidence of mating between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens,” explains Prof. Israel Hershkovitz, who co-led the research. He emphasizes that while a skeleton of a mixed-ancestry child was found in Portugal in 1998, that so-called “Lapedo Valley Child” lived just 28,000 years ago. By comparison, the Skhul child predates it by more than 100,000 years, dramatically rewriting the story of when and where these human worlds first came together.

The Blending of Cultures and Bloodlines

It is tempting to see this encounter only through the lens of genetics, but human fossils also carry traces of culture. The Skhul Cave and nearby Qafzeh Cave are sites where early humans buried their dead, sometimes with flowers, antlers, or other symbolic objects. This hints at shared practices and cultural exchange.

The discovery suggests that the two groups were not merely coexisting side by side—they were interacting socially and biologically over generations. In time, the local Neanderthal populations in the Levant were absorbed into the Homo sapiens population, disappearing not because they were replaced, but because they became part of us. The legacy of those early encounters still lives within us today, etched into our very DNA.

Science Meets Storytelling

The research team reached their conclusions only after a painstaking analysis. The micro-CT scans produced high-resolution images that allowed them to reconstruct the child’s skull in digital form. They then compared its features to those of known Neanderthal, early Homo sapiens, and other hominid populations. The inner ear, in particular, revealed a distinctly Neanderthal pattern, while the overall skull vault curved like that of modern humans.

Such anatomical hybrids are rare, but when they appear, they serve as powerful evidence of interbreeding. What makes the Skhul child so remarkable is not just the blend of features, but its antiquity—it represents the earliest physical evidence we have of human groups bridging divides that were once thought unbridgeable.

A New Vision of Human Evolution

The story of human origins is often presented as a linear march forward: Homo erectus to Neanderthals to Homo sapiens. But discoveries like the Skhul child reveal a much more intricate web, where different human populations met, mingled, and merged.

Our species did not emerge in isolation. Instead, we are the product of countless encounters across time and geography. Some groups vanished, others blended in, but all contributed threads to the tapestry of humanity.

As Prof. Hershkovitz puts it, these findings show that the Levant was not just a passageway for migration, but a “melting pot of human populations” where Neanderthals and Homo sapiens shaped each other’s futures.

A Child Who Changed the Past

The five-year-old child from Skhul Cave could not have known that their short life would one day alter our understanding of what it means to be human. Yet their bones, preserved in stone for more than a hundred millennia, speak volumes. They tell us that humanity’s story is one of connection, not division; of shared lives and shared blood.

Even 40,000 years after Neanderthals vanished as a distinct population, their presence remains with us—not just in DNA percentages, but in the story of how we became who we are. The Skhul child stands as a symbol of this truth: that we are not the heirs of one lineage, but of many.

More information: Bastien Bouvier et al, A new analysis of the neurocranium and mandible of the Skhūl I child: Taxonomic conclusions and cultural implications, L’Anthropologie (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.anthro.2025.103385