For more than a century, feathers have whispered a tantalizing promise to scientists. Wherever feathers appeared in dinosaur fossils, flight seemed close at hand. Feathers meant wings, wings meant air, and air meant the first great leap from ground to sky. But a new study has gently, decisively unsettled that story, revealing a far more intricate evolutionary tale hidden in color, growth, and loss.

Researchers examining rare feathered dinosaur fossils from eastern China have uncovered evidence that some dinosaurs once associated with early flight had already lost the ability to fly. These creatures lived around 160 million years ago, and their remains have carried a message across deep time that no bones alone could tell.

This discovery does not shout. It murmurs. And yet its implications echo across the entire history of flight.

When Feathers First Changed the Dinosaur Story

Dinosaurs did not always wear feathers. According to the research, the dinosaur lineage split from other reptiles about 240 million years ago. Not long after, many dinosaurs began developing feathers, an extraordinary biological innovation. These structures were lightweight yet strong, made of protein, and capable of both preserving body temperature and enabling flight.

Feathers transformed dinosaurs long before birds existed. They were not simply decorative coverings but dynamic tools that reshaped survival strategies. Some lineages experimented with gliding, some with insulation, and others with movement through air. Evolution was not following a single script. It was testing many possibilities at once.

Around 175 million years ago, one particularly important lineage emerged. Known as Pennaraptora, these feathered dinosaurs would eventually give rise to modern birds and would become the only dinosaur group to survive the mass extinction that ended the Mesozoic era 66 million years ago.

For a long time, scientists assumed that feathers in this group were closely tied to flight. But assumptions, as science often reminds us, are fragile things.

Anchiornis and the Gift of Unusual Preservation

The new study focused on nine fossils belonging to a Pennaraptoran dinosaur taxon called Anchiornis. These fossils come from eastern China, a region known for extraordinary preservation conditions that captured not only bones but feathers in stunning detail.

What made these particular fossils exceptional was color. The feathers were preserved with visible pigmentation, specifically white wing feathers marked by a black spot at the tip. This kind of preservation is extraordinarily rare in paleontology, and it allowed the researchers to do something almost unheard of. They could examine not just shape, but function.

The fossils were chosen precisely because they retained this feather coloration. Along the edge of the wing feathers ran a continuous line of black spots, forming a visual guide to how the feathers were arranged and how they grew. Within this pattern lay the key to understanding whether Anchiornis could fly.

Following the Quiet Clues of Feather Growth

This is where the story turns from stone to biology, and where feather researcher Dr. Yosef Kiat steps forward. An ornithologist specializing in feather research, Dr. Kiat brought modern biological knowledge into dialogue with ancient remains.

He explains, “Feathers grow for two to three weeks. Reaching their final size, they detach from the blood vessels that fed them during growth and become dead material. Worn over time, they are shed and replaced by new feathers—in a process called molting, which tells an important story.”

Molting is not random in creatures that rely on flight. In birds that must stay airborne, molting follows a careful, symmetrical pattern. Feathers are replaced gradually, maintaining balance between the wings so flight remains possible throughout the process.

In animals that do not fly, molting is different. It is irregular, uneven, and unconcerned with aerodynamic symmetry. This difference leaves behind a signature, one that can persist even after millions of years if conditions are right.

The Anchiornis fossils offered exactly those conditions.

Reading a Pattern Written in Black and White

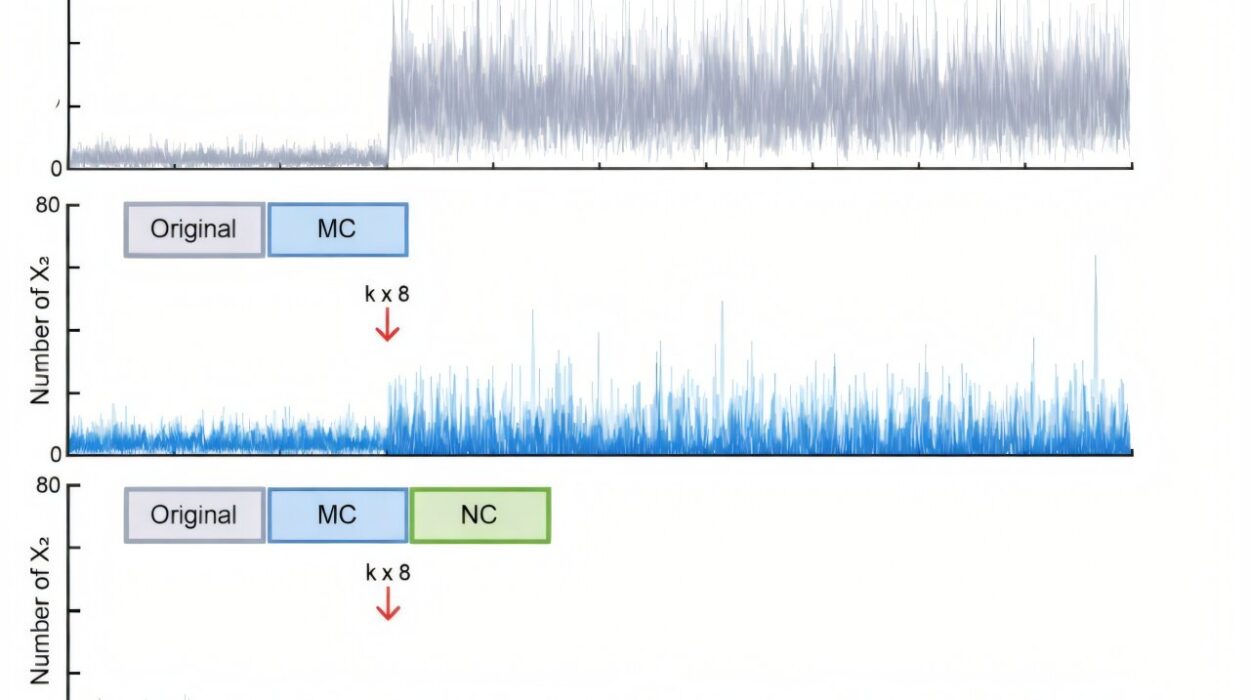

The preserved feather coloration allowed the researchers to identify wing structure in remarkable detail. The black spots at the tips of the feathers formed a clean, continuous line along the wing edge. But among these feathers, the researchers noticed something subtle and telling.

Some feathers were new. They had not yet completed their growth. Their black spots deviated from the neat black line, revealing where fresh feathers were emerging.

By examining these growing feathers across the nine fossils, the team could reconstruct the molting pattern. What they found was unexpected.

The molting was not orderly. It did not preserve symmetry. It did not follow the disciplined rhythm required for sustained flight.

Based on this evidence, Dr. Kiat reached a striking conclusion. “Based on my familiarity with modern birds, I identified a molting pattern indicating that these dinosaurs were probably flightless. This is a rare and especially exciting finding: the preserved coloration of the feathers gave us a unique opportunity to identify a functional trait of these ancient creatures—not only the body structure preserved in fossils of skeletons and bones.”

For the first time, feather growth itself had spoken across 160 million years.

Losing Flight After Finding It

The broader implications of this finding extend far beyond Anchiornis. The research team emphasizes that this discovery reshapes how we understand the evolution of flight itself.

“This finding has broad significance, as it suggests that the development of flight throughout the evolution of dinosaurs and birds was far more complex than previously believed. In fact, certain species may have developed basic flight abilities—and then lost them later in their evolution.”

Flight, it seems, was not a straight path from ground to sky. It was a winding road, with advances, retreats, and detours shaped by changing environments and survival pressures.

Dr. Kiat draws a parallel to living animals, noting that when conditions change, flight can become unnecessary or even disadvantageous. In such cases, wings remain, feathers remain, but flight fades away. The study suggests that similar evolutionary reversals happened deep in the dinosaur past.

Anchiornis now joins a growing group of dinosaurs that wore feathers without using them to fly.

A Small Detail That Changes a Big Picture

At first glance, molting may seem like a minor biological detail. It is easy to overlook, especially when compared to dramatic skeletons or massive wingspans. But in this study, molting becomes a powerful narrator.

“Feather molting seems like a small technical detail—but when examined in fossils, it can change everything we thought about the origins of flight. Anchiornis now joins the list of dinosaurs that were covered in feathers but not capable of flight, highlighting how complex and diverse wing evolution truly was,” Dr. Kiat concludes.

This complexity is the heart of the discovery. Evolution did not simply invent flight once and refine it. It experimented, abandoned, retried, and reshaped it across millions of years.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research matters because it reminds us that evolution is not a ladder but a landscape. Features we associate with progress can be lost as well as gained. Feathers do not guarantee flight, and wings do not tell the full story.

By revealing that some feathered dinosaurs lost the ability to fly, the study adds depth and realism to our understanding of how birds came to be. It shows that modern flight emerged from a tangled history of trial and change, not from a single, inevitable direction.

Perhaps most importantly, this discovery demonstrates the power of looking closely. Not just at bones, but at color. Not just at shape, but at growth. In the quiet details of molting feathers, scientists found evidence that rewrites a chapter of life’s history.

In doing so, these fossils remind us that the past still has secrets to share, and that even the smallest marks can carry the weight of lost skies.

More information: Yosef Kiat et al, Wing morphology of Anchiornis huxleyi and the evolution of molt strategies in paravian dinosaurs, Communications Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s42003-025-09019-2