For years, astronomers have been haunted by fleeting cosmic flashes that arrive without warning and vanish almost as quickly. These bursts blaze in blue and ultraviolet light, burn intensely for only a few days, and then fade into quiet afterglows of X-rays and radio waves. They are rare, with only a little more than a dozen discovered so far, and stubbornly resistant to easy explanation. Some researchers believed they were a strange kind of supernova. Others suspected a black hole feeding on gas drifting too close. Neither idea ever quite fit.

Then came the brightest one yet.

Discovered last year, this luminous fast blue optical transient, or LFBOT, was so powerful and so strange that it forced astronomers to confront an unsettling possibility. What if these flashes were not the result of stars exploding at all. What if they were something far more violent, and far more intimate.

When Old Answers Fall Apart

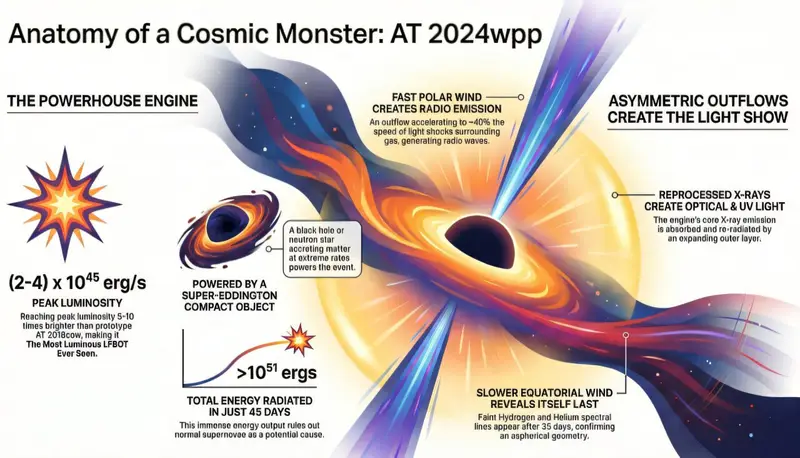

The turning point came with a simple but devastating calculation. By carefully measuring how much energy this latest burst released, researchers realized they were looking at something extraordinary. The energy pouring out was about 100 times greater than what a normal supernova could produce. To explain that much power with an exploding star would require converting roughly 10 percent of the sun’s entire rest-mass into energy in just a few weeks.

That realization broke the supernova model completely.

As Natalie LeBaron put it, “The sheer amount of radiated energy from these bursts is so large that you can’t power them with the collapse and explosion of a massive star—or any other type of normal stellar explosion.” The conclusion was unavoidable. “The main message from AT 2024wpp is that the model that we started off with is wrong. It’s definitely not caused by an exploding star.”

The mystery deepened, but clarity began to emerge.

A Star Torn Apart in Days

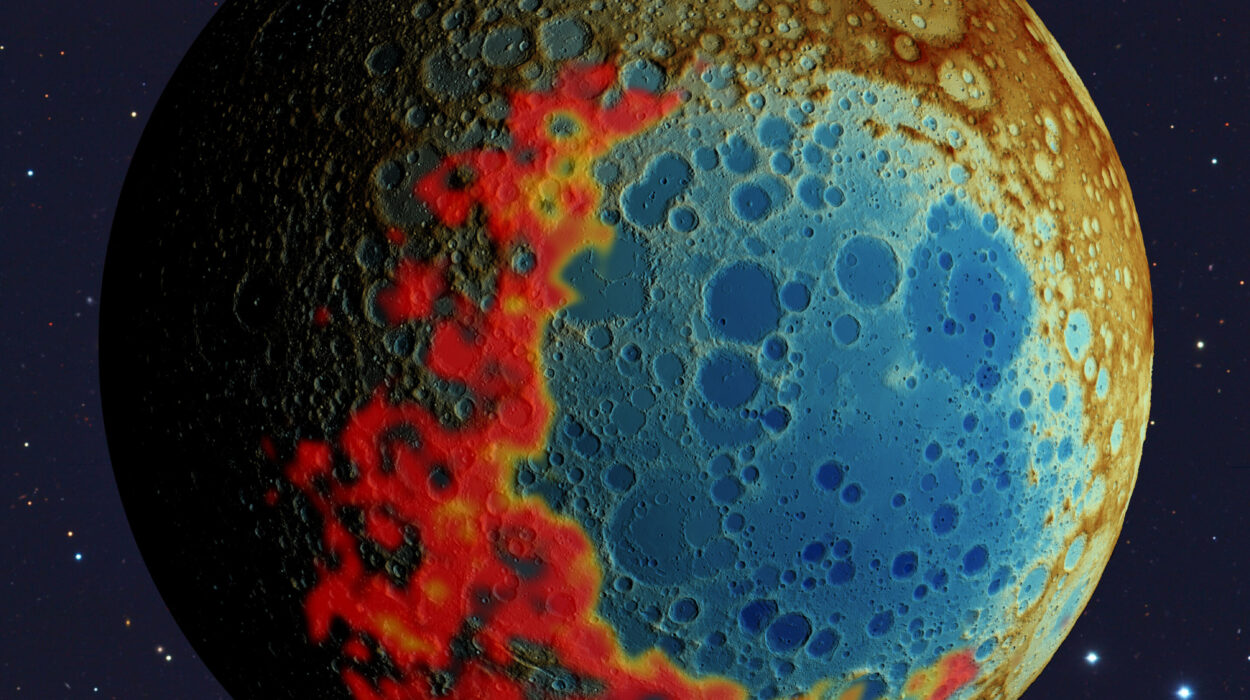

The team, led by researchers from the University of California, Berkeley, reached a striking conclusion. LFBOTs are caused by an extreme tidal disruption, a cosmic catastrophe in which a black hole up to 100 times the mass of our sun completely shreds its massive stellar companion within days.

This was not a brief encounter. The researchers believe the black hole and star had been locked together for a long time. Over that extended history, the black hole slowly siphoned material from its companion, wrapping itself in a thick halo of gas that lingered just beyond its reach.

Then came the final moment. When the companion star drifted too close, the black hole’s gravity tore it apart. Fresh stellar debris crashed into the existing halo, forming a rapidly spinning accretion disk. The collision was violent enough to unleash intense blue, ultraviolet, and X-ray light, producing the brief but brilliant flash seen from Earth.

What astronomers had been witnessing all along was not an explosion outward, but a destruction inward.

Jets, Light, and a Violent Aftermath

The destruction did not end with the star’s shredding. Much of the star’s gas spiraled toward the black hole’s poles and was blasted outward as powerful jets. These jets, the researchers calculated, traveled at about 40 percent of the speed of light. When they slammed into surrounding gas, they generated radio waves that lingered long after the initial optical flash faded.

This sequence of events explains the strange behavior that puzzled astronomers for years. The fast rise in brightness, the intense blue and ultraviolet light, the fading X-rays, and the late radio emissions all fit together as chapters in a single violent story.

Each wavelength carried a different piece of the narrative, revealing how matter behaved as it was torn apart, swallowed, and flung back into space.

A Black Hole in the Middle Ground

The black hole responsible for this destruction belongs to an especially intriguing class. Its mass places it in a range often referred to as intermediate-mass black holes. Astronomers know that black holes heavier than 100 suns exist because their mergers have been detected by gravitational wave experiments such as the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO. Yet these black holes have never been directly observed, and how they grow so large remains a mystery.

This is where LFBOTs become particularly valuable.

As Raffaella Margutti explained, “Theorists have come up with many ways to explain how we get these large black holes, to explain what LIGO sees.” She emphasized that “LFBOTs allow you to get at this question from a completely different angle. They also allow us to characterize the precise location where these things are inside their host galaxy, which adds more context in trying to understand how we end up with this setup—a very large black hole and a companion.”

These events offer a rare window into environments where massive black holes and massive stars evolve together, shaping each other’s fate.

The Curious Family of Fast Blue Flashes

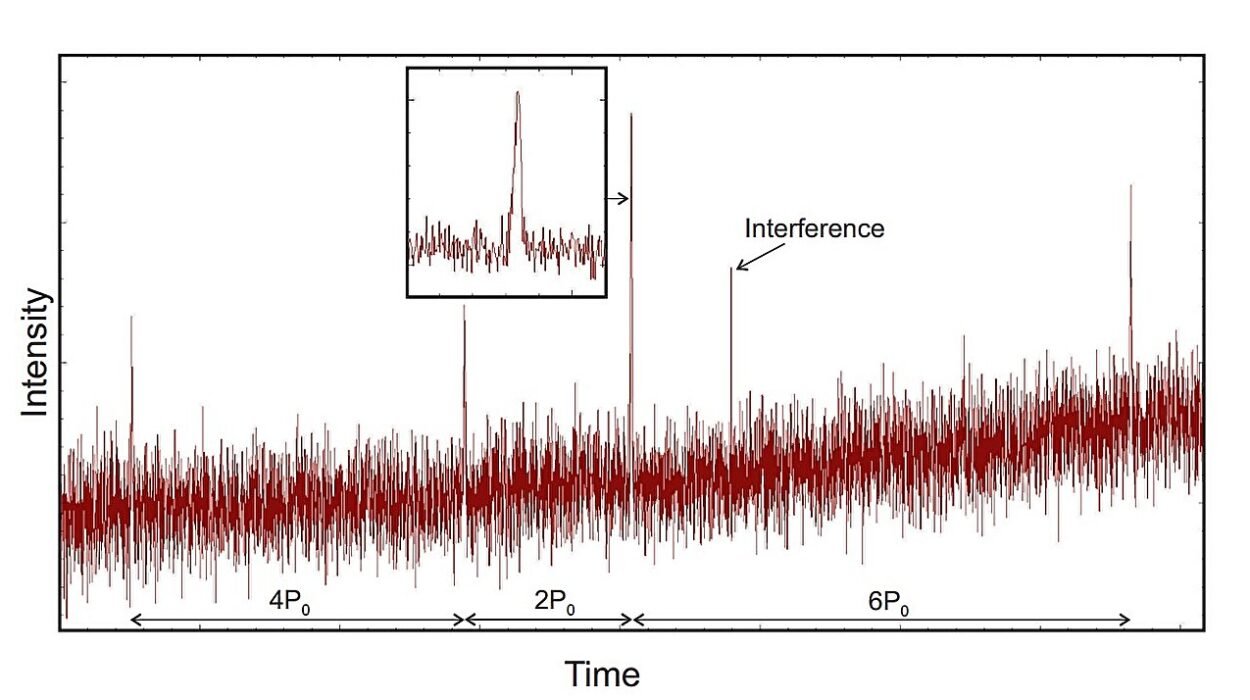

LFBOTs earned their name honestly. They are luminous enough to be seen across hundreds of millions to billions of light-years, fast enough to fade within days, and blue because they shine most strongly at high-energy wavelengths from optical blue through ultraviolet and X-rays.

The first example was spotted in 2014, but the first with enough data to analyze arrived in 2018. Officially called AT 2018cow, it quickly became known simply as the Cow. Astronomers, perhaps relieved to give these frightening phenomena playful nicknames, followed with the Koala, the Tasmanian Devil, and the Finch.

The newest member of this strange family is AT 2024wpp, informally dubbed the Woodpecker. It stands out as the brightest LFBOT ever observed, between five and ten times more luminous than the Cow, and located 1.1 billion light-years away.

Two studies analyzing this event have been accepted by The Astrophysical Journal Letters, one focusing on X-ray and radio emissions and the other on optical, ultraviolet, and near-infrared light. Together, they form the most complete picture of an LFBOT yet.

The Star That Met Its End

The star destroyed in this event was no lightweight. Researchers estimate it had more than ten times the mass of the sun. It may have been a Wolf-Rayet star, a type of hot, evolved star that has already burned through much of its hydrogen. This would neatly explain why the hydrogen emission from AT 2024wpp was weak.

Like most LFBOTs, this event occurred in a galaxy with active star formation, where large, young stars are common. In such crowded and energetic environments, close binary systems involving massive stars and black holes are more likely to form.

The setting matters because it shapes the story long before the final catastrophe. The environment determines how stars grow, how black holes feed, and how often these rare, luminous events occur.

Watching a Cosmic Crime Scene

To unravel this story, astronomers relied on an impressive array of observational tools. Three X-ray telescopes were used, NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, Swift-XRT, and the Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array. Radio emissions were captured by facilities such as the Atacama Large Millimeter submillimeter Array and CSIRO’s Australia Telescope Compact Array. Ultraviolet and optical data came from the Ultra-Violet Optical Telescope on NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory and from ground-based observatories including Keck, Lick, and Gemini.

Each telescope added a layer of detail, allowing researchers to reconstruct the sequence of events with remarkable precision. The result was not just a snapshot, but a time-lapse of destruction unfolding across the electromagnetic spectrum.

A Future Filled With Blue Light

Despite their importance, LFBOTs are currently rare finds. Astronomers detect only about one per year. That scarcity may soon change. Because these events emit large amounts of ultraviolet light, upcoming space-based ultraviolet telescopes could transform the field.

Two planned missions, ULTRASAT and UVEX, are expected to play a critical role. They will allow astronomers to discover LFBOTs earlier and study them before they reach peak brightness. This early view is essential for understanding how these systems form and how diverse their environments can be.

As Nayana A.J. explained, “Right now, we find only about one LFBOT per year. But once we have UV telescopes in place in space, then finding LFBOTs will become routine, like detecting gamma ray bursts today.”

Routine detection does not mean routine significance. Each new event will carry fresh clues about black holes, stars, and the violent processes that connect them.

Why This Discovery Matters

This breakthrough resolves a decade-long puzzle and reshapes how astronomers interpret some of the brightest, fastest flashes in the universe. By showing that LFBOTs are neither supernovae nor simple black hole feeding events, the research reveals an entirely different kind of stellar catastrophe, one where a massive star is torn apart by a black hole companion in a matter of days.

Beyond solving a mystery, this work opens a powerful new way to study intermediate-mass black holes, objects that have long existed at the edge of observation and theory. LFBOTs offer a rare opportunity to watch these black holes in action, embedded in real galaxies, interacting with real stars.

In the end, these brief blue flashes remind us that the universe still has the power to surprise. Even after decades of observation, nature can present phenomena so extreme that they force scientists to discard old ideas and build new ones. LFBOTs are not just cosmic fireworks. They are messages from the most violent corners of the universe, telling a story of destruction, evolution, and discovery that we are only beginning to understand.

More information: A. J. Nayana et al, The Most Luminous Known Fast Blue Optical Transient AT 2024wpp: Unprecedented Evolution and Properties in the X-rays and Radio, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2509.00952

Natalie LeBaron et al, The Most Luminous Known Fast Blue Optical Transient AT 2024wpp: Unprecedented Evolution and Properties in the Ultraviolet to the Near-Infrared, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2509.00951