Mars has a way of humbling Earthly assumptions. What thrives in our familiar soil may struggle, or even fail, in the planet’s rusty dust. One of the most troubling challenges hiding in Martian ground is perchlorate, a toxic, chlorine-containing chemical detected by multiple space missions. For life as we know it, perchlorate is hostile. Yet for a team of researchers in India, this same chemical has revealed an unexpected twist in the story of building on another world.

At the Indian Institute of Science, scientists have been asking a deceptively simple question: if humans ever try to build habitats on Mars using local soil, how will Earth bacteria behave in such an alien environment? As Aloke Kumar, Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering at IISc, puts it, Mars is not just far away, it is fundamentally unfamiliar. Understanding how terrestrial organisms respond there is, in his words, a “very, very important scientific question.”

The answer, it turns out, is more surprising than anyone expected.

Bricks Grown, Not Fired

The story begins with an unusual idea: instead of hauling heavy construction materials from Earth, why not grow bricks directly from Martian soil? In earlier studies, Kumar’s group explored this concept using the soil bacterium Sporosarcina pasteurii. When fed a mixture containing urea and calcium, the bacterium produces calcium carbonate crystals. These crystals act like microscopic glue, binding loose soil particles together in a process known as biocementation.

Add a natural adhesive called guar gum, derived from guar beans, and the result is a solid, brick-like material formed without firing kilns or pouring traditional cement. The approach holds promise not just for Mars or the Moon, but also as a more sustainable alternative to carbon-intensive cement on Earth.

But Mars is not a sterile laboratory setup. Its soil chemistry includes hazards that could derail the entire process.

A Tougher Microbe from Home Soil

For the new study, published in PLOS One, the researchers decided to raise the stakes. Instead of relying on a previously used bacterial strain, they turned to a more robust, native version they had isolated from the soils of Bengaluru. First, they confirmed that this local strain could form the same mineral precipitates needed to bind soil.

Then came the real test. Could this bacterium survive perchlorate, which can exist at levels of up to 1% in Martian soils?

To find out, the IISc team teamed up with Punyasloke Bhadury from the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research in Kolkata. What they observed was not a simple tale of survival or failure, but something far more complex.

Stress, Shape-Shifting, and Survival

When exposed to perchlorate, the bacterial cells showed clear signs of stress. Their growth slowed. Their shape changed, becoming more circular. Instead of spreading out freely, they began to clump together, forming structures that resembled multicellular communities.

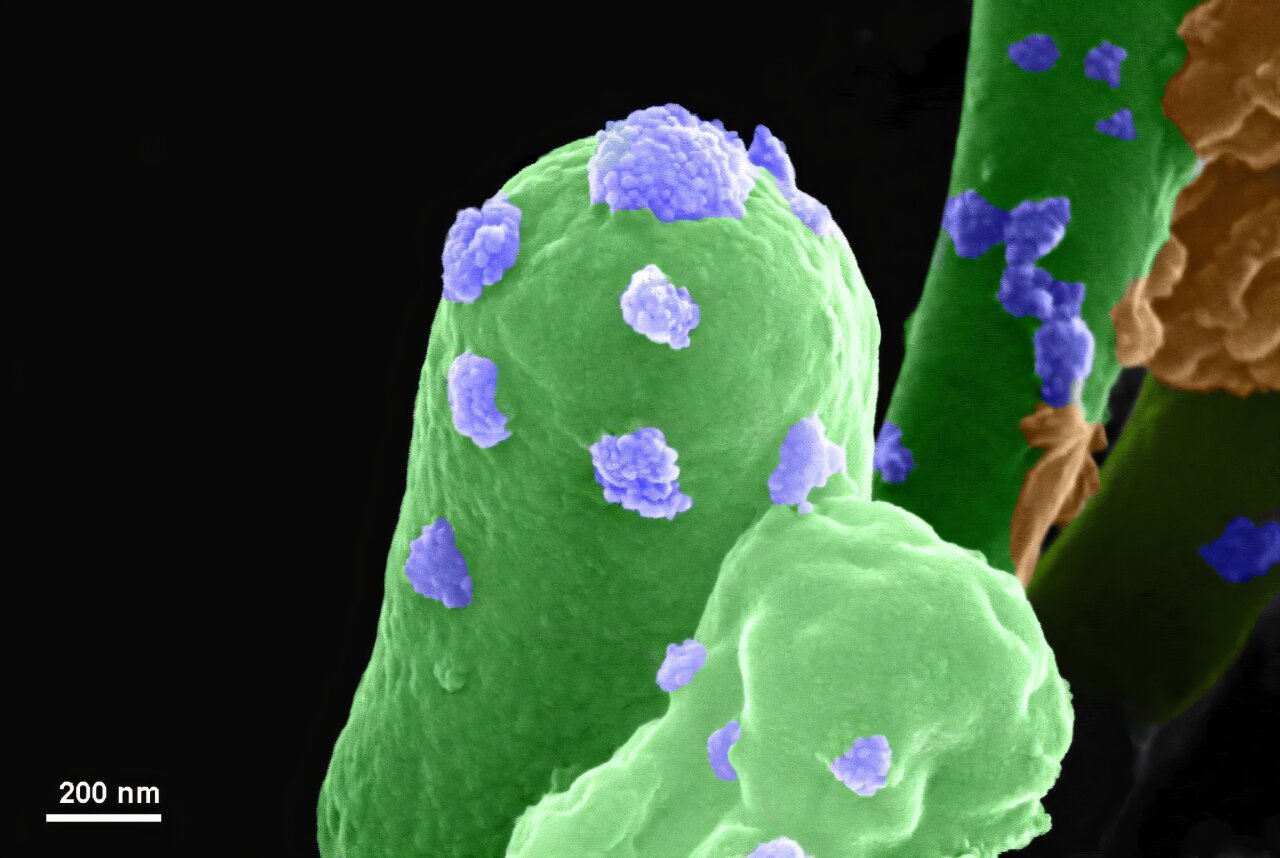

At the same time, the bacteria started releasing larger amounts of proteins and molecules into their surroundings. These substances formed what scientists call an extracellular matrix, or ECM. Under electron microscopes, the ECM revealed itself as a delicate web, creating tiny microbridges between bacterial cells and the mineral precipitates forming around them.

The presence of perchlorate also coincided with the formation of more calcium chloride-like precipitates, suggesting that the stress response was reshaping the bacteria’s chemistry as well as its behavior.

On its own, perchlorate was clearly harmful. The bacteria were struggling. But the story did not end there.

A Dangerous Chemical Turns Helpful

To see how perchlorate would affect actual brick formation, the researchers carefully added it to synthetic Martian soil in the lab. Such simulants normally exclude perchlorate because of its flammability, but controlled conditions allowed the team to test its influence safely.

What they found defied expectations. When perchlorate was present alongside guar gum and the catalyst nickel chloride, the bacteria became better at binding soil particles together. The resulting bricks were stronger than those made without perchlorate.

Studied in isolation, perchlorate was a stressor. In the complex environment of biocemented bricks, with the right supporting ingredients, it became an unexpected ally.

“When the effect of perchlorate on just the bacteria is studied in isolation, it is a stressful factor,” explains Swati Dubey, the study’s first author. “But in the bricks, with the right ingredients in the mixture, perchlorate is helping.”

Microbridges and a New Hypothesis

Why would a toxic chemical improve brick strength? The team believes the answer may lie in the ECM microbridges. These tiny connections could be funneling nutrients more efficiently to stressed bacterial cells, helping them continue producing the mineral glue needed for biocementation even under harsh conditions.

It is still a hypothesis, but one the researchers are eager to test. Future experiments aim to push the system even closer to Martian reality by examining how the bacteria perform in a high CO₂ atmosphere, another defining feature of Mars that can be simulated in the lab.

Each step adds nuance to the picture. Mars may be hostile, but life’s responses to hostility can sometimes produce unexpected advantages.

Building the Future, One Microbe at a Time

The implications of this work extend far beyond laboratory bricks. The researchers envision biocementation as a way to reduce reliance on traditional cement, both on Earth and on other worlds. Cement production is energy-intensive and carbon-heavy. A biological alternative, grown rather than manufactured, offers a more sustainable path.

For space exploration, the promise is even more concrete. Shubhanshu Shukla, an ISRO astronaut and co-author of the study, points out that uneven terrain has already caused problems for lunar landers. Technologies that allow astronauts to stabilize soil could help build roads, launch pads, and rover landing sites, making missions safer and more reliable.

The guiding philosophy is in situ resource utilization. Instead of transporting massive amounts of material from Earth, future explorers could use what is already there. Martian soil, combined with resilient bacteria and a few carefully chosen additives, might one day support human structures.

Why This Research Matters

This study reveals something profound about the intersection of biology and alien environments. A chemical once seen purely as an obstacle becomes, under the right conditions, a contributor to strength. By showing how perchlorate can both stress bacteria and enhance biocementation, the research adds depth to our understanding of how life adapts and reshapes its surroundings.

For Mars, it suggests that the planet’s own chemistry might not just resist human presence, but could be harnessed to support it. For Earth, it offers a glimpse of construction methods that work with biology instead of against it.

In the quiet interactions between stressed microbes and toxic salts, a new approach to building is taking shape. If humans ever settle on Mars, their first bricks may owe their strength not to fire or steel, but to bacteria learning how to survive on an alien world.

Study Details

Swati Dubey et al, Effect of perchlorate on biocementation capable bacteria and Martian bricks, PLOS One (2026). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0340252