For decades, astronomers have been assembling a family album of planetary systems. They have crisp baby pictures showing planets being born inside bright, gas-rich disks. They also have old portraits of settled systems, calm and orderly, long after the chaos has faded. But the middle chapters were missing. The awkward, turbulent years when planets were no longer infants but not yet adults had remained frustratingly out of reach.

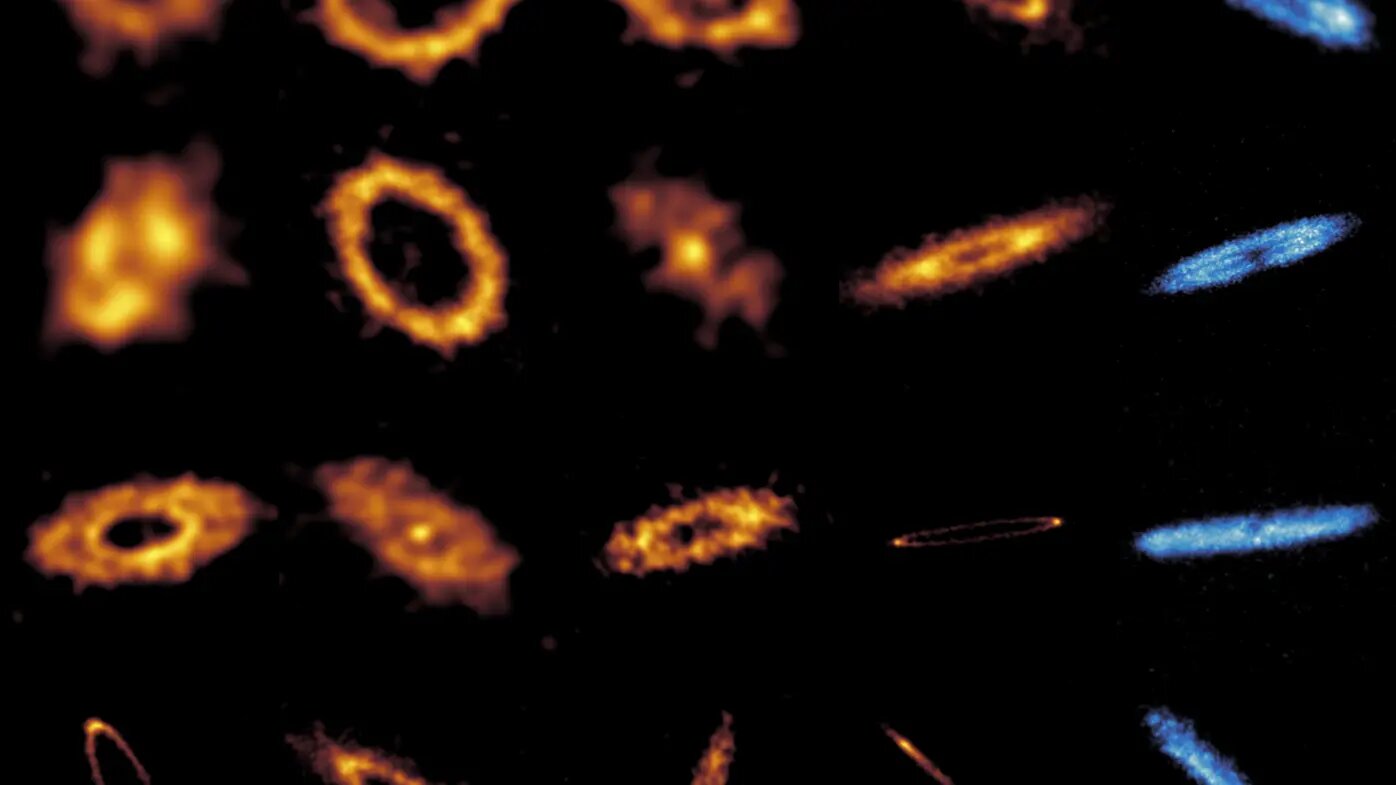

Now, for the first time, that gap has begun to close. A sweeping new survey called the ALMA survey to Resolve exoKuiper belt Substructures, or ARKS, has captured the sharpest images ever of 24 debris disks—dusty belts left behind after planets finish forming. These observations, made using the powerful Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and published in Astronomy & Astrophysics, offer a rare glimpse into what planetary systems look like during their cosmic teenage years.

The Awkward Adolescence of Planetary Systems

Debris disks occupy a strange and revealing moment in a star system’s life. They are no longer cradles of newborn planets, glowing with thick clouds of gas. Yet they are not quiet, settled places either. Instead, they are shaped by relentless collisions, gravitational nudges, and leftover debris from worlds that have already taken shape.

Astronomers describe this phase as collision-dominated, a time when planets are still rearranging themselves and smaller bodies smash together, grinding into dust. Thomas Henning of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, one of the project’s leaders, explains that debris disks represent this violent stage in planet formation. They are records written in dust, tracing the forces that shaped entire planetary families.

Until now, these disks were extraordinarily hard to study. They are faint, sometimes hundreds or even thousands of times dimmer than the disks seen around younger stars. For years, they slipped through astronomical surveys, too subtle to photograph clearly. The teenage years, it seemed, were destined to stay hidden.

How ALMA Learned to See the Unseen

The breakthrough came from ALMA, a vast network of radio telescopes spread across the Chilean desert. Unlike traditional telescopes, ALMA does not take pictures in the familiar sense. Instead, it collects faint radio signals emitted by tiny dust grains and molecules orbiting distant stars. Each telescope contributes a piece of the signal, and only after careful processing are these signals woven together into a detailed image.

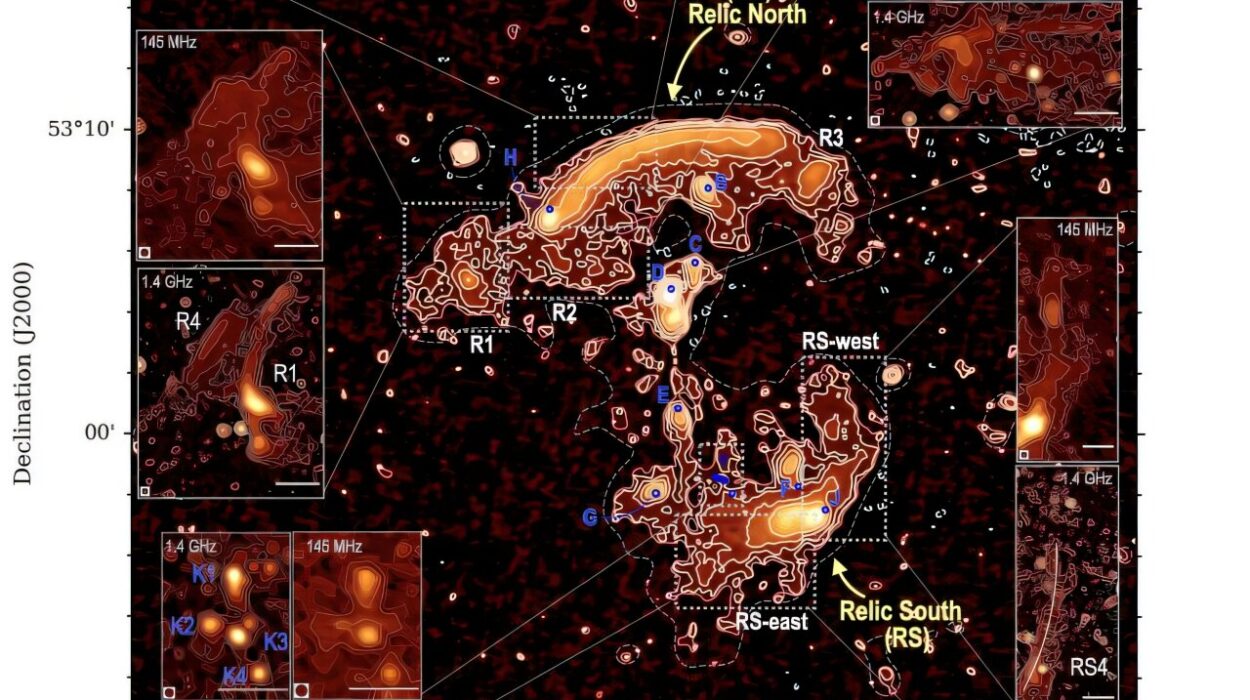

With this technique, the ARKS team achieved something unprecedented. They revealed debris disks in striking clarity, exposing structures that had never been seen before. Where astronomers once expected simple rings, they now see complexity everywhere.

Some disks show multiple rings, others stretch into wide, smooth halos, and many display sharp edges, arcs, or uneven clumps of material. Sebastián Marino, program lead for ARKS, describes the scene as one of remarkable diversity, with each disk telling its own story of motion, impact, and gravitational influence.

A Cosmic Mirror of Our Own Past

These distant disks are not just curiosities. They are time machines. Our own solar system passed through a similar phase billions of years ago, preserved today in the Kuiper Belt, a ring of icy debris beyond Neptune. That region still holds the scars of ancient collisions and planetary migrations.

By studying debris disks around other stars, astronomers can peer into a stage our solar system once endured. The ARKS survey opens a window into an era when planets jostled for position, sometimes swapping orbits, while massive impacts reshaped worlds. It was a time when chaos ruled, and stability was still being negotiated.

Meredith Hughes, an Associate Professor at Wesleyan University and a co-leader of the study, compares the new observations to filling in the missing pages of a family album. The baby photos were always there, and the mature portraits were familiar. What was missing were the images of growth, struggle, and change.

Signs of Violence Written in Dust

One of the most striking results of ARKS is how many disks show clear signs of disturbance. About one-third of the observed systems contain obvious substructures, such as distinct gaps or multiple rings. These features suggest the influence of planets, either as lingering fingerprints from earlier formation stages or as long-term sculptors reshaping their surroundings.

In some disks, dust appears vertically “puffed up,” hinting at regions of calm coexisting with zones of chaos. This pattern echoes what astronomers see in our own Kuiper Belt, where relatively undisturbed objects share space with bodies scattered by Neptune’s ancient migration.

Even more surprising is the discovery that several debris disks retain gas far longer than expected. This lingering gas may influence the chemistry of growing planets or gently push dust into expansive halos, altering the system’s evolution in subtle but profound ways.

Lopsided Belts and Invisible Influences

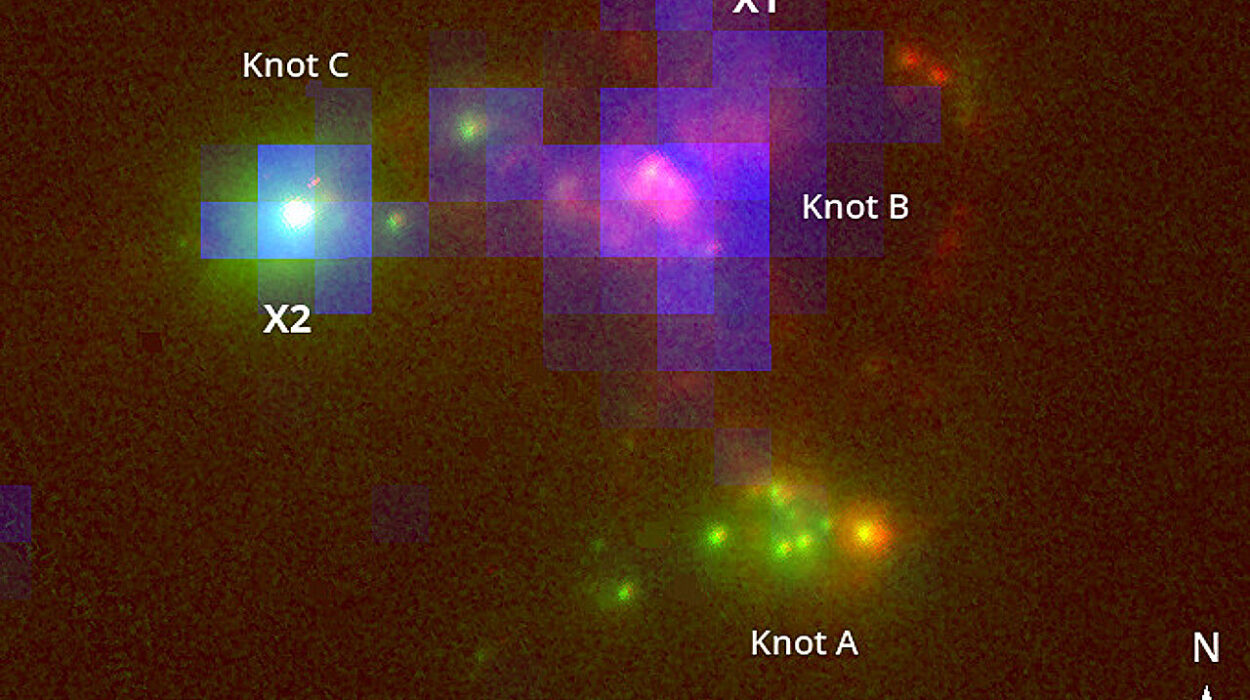

Many of the disks imaged by ARKS are not symmetrical. Instead, they are lopsided, with bright arcs, eccentric shapes, or dense clumps of material gathered on one side. These asymmetries hint at unseen forces at work.

The most likely culprits are planets that have already formed but remain invisible to current instruments. Their gravitational pull can herd dust, carve gaps, or create arcs as they orbit their stars. Some of these features may also be scars left behind by planetary migration or by interactions between dust and the surviving gas.

What makes these observations especially powerful is that they do not stand alone. Alongside ALMA’s images, astronomers are also using direct imaging and radial velocity studies to search for young planets in these same systems. Together, these approaches allow scientists to connect disk structures with the planets shaping them.

A Youth Marked by Chaos and Creation

The emerging picture is one of transition and turmoil. According to Luca Matrà, another co-leader of the survey, debris disks capture a moment when planetary orbits are being scrambled and enormous impacts can still occur. Events on this scale may resemble the collision that formed Earth’s moon, a reminder that even life-shaping moments can arise from cosmic violence.

By examining dozens of disks around stars of different ages and types, the ARKS team can begin to ask deeper questions. Are these chaotic features inherited from the earliest days of planet formation, or are they carved later by fully formed planets? Do all planetary systems endure such upheaval, or was our solar system unusually dramatic?

The answers lie in the patterns now emerging from the data.

Opening the Door for Future Discoveries

One of the most important aspects of the ARKS survey is that all of its observations and processed data are being released publicly. This means astronomers around the world can explore these disks, test new ideas, and search for patterns that might otherwise go unnoticed.

The survey sets a new benchmark, often described as a “DSHARP-for-debris-disks,” establishing a gold standard for future studies. It provides a detailed map of where to look for young planets and how to interpret the subtle clues left behind by their formation and migration.

Why These Teenage Years Matter

Understanding debris disks is about more than dusty rings around distant stars. It is about understanding origins. These disks record a formative chapter in planetary history, one that shaped worlds, influenced atmospheres, and determined which planets survived and which were lost.

As Meredith Hughes puts it, this work gives astronomers a new lens for interpreting familiar features closer to home, from the craters on the Moon to the structure of the Kuiper Belt. It connects the distant and the familiar, showing that our solar system’s past was likely not unique, but part of a broader cosmic story.

By finally capturing these teenage years in detail, the ARKS survey transforms mystery into narrative. It reveals that planetary systems, like families, grow through turbulence, experimentation, and change. And in doing so, it brings us one step closer to understanding how worlds like our own come to be.

Study Details

S. Marino et al. The ALMA survey to Resolve exoKuiper belt Substructures (ARKS) — I: Motivation, sample, data reduction, and results overview. Astronomy & Astrophysics (2026). DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202556489. www.mpg.de/26005548/arks_part_ … verview_preprint.pdf