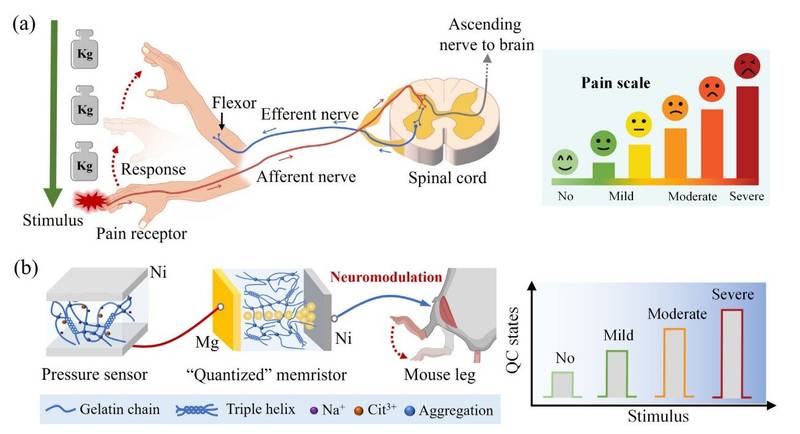

Pain is not loud, yet it speaks first. Long before a burn scars the skin or a cut draws blood, tiny sentinels scattered throughout the body send urgent messages inward. These sentinels are nociceptors, microscopic sensors whose sole responsibility is to notice danger and warn the brain and spinal cord. They do not heal wounds or stop injuries. They alert us, fast and faithfully, so we can pull away before damage deepens.

For decades, scientists have tried to teach machines this same language. If artificial systems could sense pain the way living tissue does, they might protect prosthetic limbs, guide rehabilitation, and make human–machine interactions feel more intuitive and alive. Yet pain has proven difficult to replicate. It is not simply on or off. It comes in shades, intensities, and fades with time.

Now, a team of scientists from Northeast Normal University in China has taken a remarkable step toward solving this problem. They have created a jelly-like artificial nociceptive nerve pathway that does something rare in machines: it feels pain in levels.

A Tiny Device With a Memory of Suffering

At the heart of this artificial nerve lies an unusual electronic component called a memristor. Unlike ordinary electronic parts that merely allow electricity to pass or block it, a memristor remembers. It retains a record of how much electrical current has flowed through it before, shaping how it responds in the future.

This memory-like behavior made memristors attractive to researchers seeking to mimic the nervous system. In biological nerves, past experiences influence future responses. Pain pathways are especially sensitive to this history, responding more strongly to repeated harm.

The memristor used in this study exhibited something known as quantized conductance, or QC. Instead of allowing electricity to flow smoothly, the current moves in discrete steps. This detail changed everything. Rather than responding to a stimulus with a simple yes or no, the artificial receptor could respond in four distinct electrical states.

Those four states mirrored the human pain experience itself: no pain, mild pain, moderate pain, and severe pain. The artificial nociceptor was no longer a binary switch. It had become a storyteller, capable of describing intensity.

When Gelatin Becomes a Nerve

The researchers did not rely on rigid electronics alone. They turned to a surprisingly familiar material: gelatin. By using two different gelatin films, the team constructed a system that felt more like living tissue than traditional circuitry.

One gelatin film, made with 10 wt.% gelatin, acted as a pressure sensor. Another, made with 1 wt.% gelatin, formed the memristor itself. When these two components were connected in series, they created what the researchers described as an artificial nerve.

This jelly-like pathway could sense mechanical pressure and translate it into electrical signals that changed step by step, depending on intensity. To test this, the researchers applied forces ranging from 9 to 45 kPa. Each increase in pressure shifted the system into a higher conductance state, clearly distinguishing between levels of pain.

What emerged was not just sensitivity, but clarity. The artificial nociceptor did not confuse gentle pressure with harm. It recognized escalation, just as human nerves do.

Beyond Switching On and Off

Earlier attempts to create artificial pain sensors leaned heavily on traditional semiconductor technology. While technically capable, these systems demanded extremely complicated and bulky circuits just to mimic the simplest pain responses. The result was functional, but far from elegant or lifelike.

Memristors changed that landscape. With just two terminals and a natural ability to mimic neural behavior, they allowed researchers to build pain sensors that respond more strongly to repeated stimuli. Crucially, these artificial nociceptors did not adapt away from pain over time, preserving sensitivity in a way that mirrors biological systems.

Yet even these advances had limits. Most artificial pain sensors still lacked two essential qualities: the ability to grade pain intensity and the ability to self-heal. Without these, artificial pain remained a rough imitation.

The new gelatin-based system addressed both challenges at once.

The Surprising Act of Healing Itself

Pain in living organisms fades as healing occurs. Damaged tissue repairs itself, and the alarm quiets. The researchers wanted to know whether their artificial nociceptor could do something similar.

To find out, they introduced physical damage directly into the gelatin sensors. Cuts as wide as 50.7 µm were made in the material, disrupting its electrical pathways. Then, the researchers applied heat at 60 °C for 20 minutes.

What happened next was striking. The cuts disappeared. The gelatin reformed. Electrical conduction returned to its original state.

This self-healing behavior meant that the artificial nociceptor could recover from damage without replacement or repair. Even more importantly, the fading of pain signals mirrored the biological process of recovery. The system did not stay locked in a state of injury.

A Conversation With Living Nerves

The most dramatic moment in the study came when the artificial pain sensor stepped out of the laboratory bench and into a living body.

The researchers connected the artificial nociceptor to the sciatic nerve of an anesthetized mouse. When pressure was applied to the sensor, it generated electrical signals that traveled into the nerve. The mouse’s muscles contracted in response.

This movement was not random. It resembled a natural avoidance reflex, the kind driven by pain signals in living organisms. The artificial system had successfully communicated with biological tissue, speaking a language the nervous system understood.

In that moment, the line between synthetic and organic blurred.

Why Graded Pain Changes Everything

Pain is often seen as something to eliminate, but it exists for a reason. It protects. It warns. It teaches boundaries. A machine that can sense only damage or no damage lacks this nuance. It cannot decide when to respond gently and when to react urgently.

By introducing four distinct pain levels, this artificial nociceptor adds a missing dimension to human–machine interaction. A prosthetic limb equipped with such sensors could respond differently to light contact versus dangerous pressure. Rehabilitation devices could adapt feedback based on intensity rather than simple thresholds.

Just as importantly, self-healing materials reduce failure and extend lifespan. Artificial systems that repair themselves after damage move closer to the resilience of living tissue.

From Jelly to the Future

The researchers believe that bio-inspired artificial nociceptive systems like this one could push the boundaries of neuroprosthetics and intuitive human–machine interaction. By mimicking not just the presence of pain but its depth and recovery, machines may become safer, smarter, and more responsive partners to the human body.

This work does not claim to recreate pain itself. Instead, it captures pain’s structure, its gradation, and its fading. That distinction matters. It respects pain’s role without inflicting suffering.

The findings, published in Advanced Functional Materials, suggest a future where machines do not merely obey commands but understand limits.

Why This Research Matters

This study matters because it reframes how technology listens to the body. Pain is one of our most ancient survival tools, refined over millions of years. By translating its logic into a jelly-like artificial nerve, the researchers have shown that softness, memory, and adaptability belong in advanced electronics.

For people recovering from injury, for those relying on prosthetics, and for anyone interacting with machines that touch the body, systems that can sense harm before it becomes damage could change daily life. They could prevent injury, guide healing, and restore a sense of trust between humans and the tools they depend on.

In teaching a piece of gel to feel pain in levels, scientists have taken a small but meaningful step toward technology that understands us not just as users, but as living, vulnerable beings.

Study Details

Xuanyu Shan et al, Bioinspired Artificial Nociceptor Based on Quantized Conductance Memristor With Pain Rating, Self‐Healing, and Neuromodulation Capabilities, Advanced Functional Materials (2025). DOI: 10.1002/adfm.202528900