For decades, the quiet power behind modern technology has depended on materials that come with hidden costs. The strongest magnets in our phones, hard drives, medical scanners, and motors draw their strength from rare-earth elements or precious metals, materials that are expensive to mine, environmentally damaging, and fragile in global supply chains. Engineers have long accepted this trade-off as unavoidable, a necessary compromise for performance. But in a physics lab at Georgetown University, a different story began to unfold—one that challenges this assumption at its core.

The story starts with a simple but stubborn question: can a magnet be strong without relying on rare or precious materials? The answer, it turns out, is yes. And the path to that answer leads through an unusual family of materials known as high-entropy borides, built entirely from earth-abundant transition metals and boron.

The Direction That Makes a Magnet Powerful

To understand why this discovery matters, it helps to understand what makes a magnet useful in the first place. A magnet’s strength is not only about how strongly it can attract metal. Equally important is whether its internal magnetization prefers to point in one stable direction. This property, called magnetic anisotropy, is what allows magnets to store information reliably, resist demagnetization, and perform consistently in demanding technologies.

Modern magnetic technologies depend on materials with very strong anisotropy. Today, the best performers almost always rely on rare-earth elements. In thin-film applications, such as next-generation magnetic recording media, alloys of iron and platinum have become the standard. These materials work beautifully, but they come with a heavy price, both economic and environmental. For years, scientists have searched for alternatives based on abundant elements, but the challenge has proven formidable.

A Different Way to Build Materials

The team at Georgetown, led by professors Kai Liu and Gen Yin, along with graduate student Willie Beeson, approached the problem from a fresh angle. Instead of tweaking known materials, they turned to high-entropy alloys, a class of materials that contain five or more elements mixed in near-equal proportions. These alloys offer an enormous playground for discovery, because their complex compositions can produce electronic structures and properties that do not exist in simpler materials.

Yet high-entropy alloys come with a problem of their own. Most of them crystallize into chemically disordered cubic structures, shapes that are poorly suited for strong magnetic anisotropy. A cube, by its very symmetry, offers too many equivalent directions for magnetization to settle firmly into just one.

Rather than abandoning the approach, the researchers looked for a way around this limitation. Their solution was elegant. They focused on high-entropy borides, materials in which boron plays a crucial role by encouraging chemical ordering and reducing crystal symmetry. Lower symmetry means fewer equivalent directions, and that opens the door to stronger anisotropy.

Stretching the Cube Until It Changes the Rules

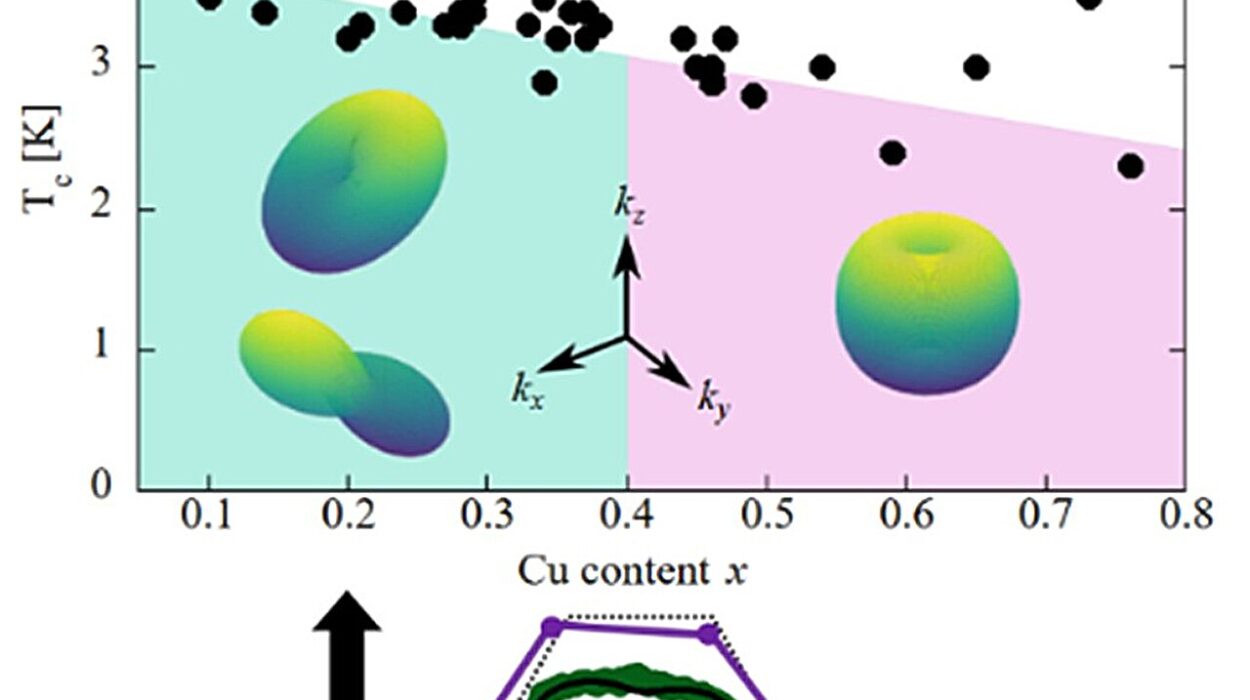

The specific structure the team targeted is known as the C16 phase, a crystal structure with tetragonal symmetry. One way to imagine it is as a cube that has been stretched along one axis, breaking the perfect balance of its geometry. This structure has been known in simpler boron-based materials made from just two or three elements, but it has remained largely unexplored in complex, multi-element systems.

By aiming for this stretched, lower-symmetry structure, the researchers created the conditions needed for magnetization to prefer a specific direction. The challenge was not only theoretical. These materials had to be made, tested, and refined in the real world.

Making Dozens of Materials at Once

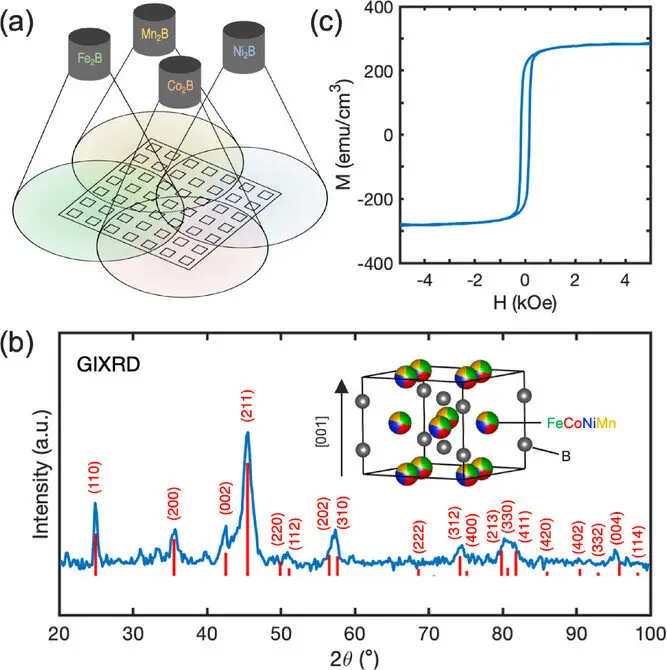

In Liu’s lab, Beeson used a combinatorial sputtering method to synthesize the new materials. In this process, atoms from multiple target materials are ejected and mixed together before settling onto a heated substrate. By the time they land, the atoms are thoroughly blended, forming a thin film with a carefully controlled composition.

This method has a remarkable advantage. On a single substrate, around 50 different samples can be created simultaneously. Each sample shares the same growth conditions but differs slightly in composition. This allowed the team to explore a vast landscape of material combinations rapidly and systematically, something that would be impractical using traditional, one-sample-at-a-time approaches.

As the compositions changed, something remarkable happened. By introducing multiple 3d transition metals and allowing them to mix within the boride structure, the researchers found that the magnetization began to lock into a preferred direction with increasing strength. The magnetic anisotropy grew significantly, far beyond what had been previously reported for rare-earth-free high-entropy materials.

A New Class of Magnets Emerges

What the team ultimately realized was that they had uncovered something entirely new. They had created the first high-entropy borides in the C16 crystal structure using only earth-abundant 3d transition metals. These materials were not only ordered, rather than disordered, but they also displayed a level of anisotropy that approached that of rare-earth permanent magnets.

Some of the newly discovered quinary boride compositions, made from five elements, showed performance that exceeded all previously reported values for rare-earth-free high-entropy materials. This was not a marginal improvement. It was a leap that redefined what was thought possible without relying on scarce elements.

When Theory Confirms the Surprise

Experimental results can be thrilling, but they become truly powerful when theory agrees. In this case, density functional theory calculations mirrored what the researchers observed in the lab. The calculations confirmed the trends seen in the experiments and revealed why the anisotropy was so strong.

The key lay in the optimized electronic structure of the materials. In particular, the valence electron concentration and the effective magnetic moment emerged as central factors. By carefully tuning these properties through chemical mixing, the researchers were able to engineer anisotropy at a fundamental level. This alignment between theory and experiment gave the team confidence that they were not seeing a fluke, but uncovering a new and robust design strategy.

Looking Ahead, Faster and Smarter

The work does not end with this discovery. According to Yin, the team is continuing to explore even better materials by varying compositions and experimenting with different underlying crystal structures. They are also looking toward machine learning as a way to accelerate progress, using computational tools to navigate the immense compositional space more efficiently.

What began as an exploration of one crystal structure has opened a broader vision of what ordered high-entropy materials can offer, not just for magnetism but for advanced functional properties more generally.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research matters because it changes the rules of the game. By demonstrating that strong magnetic anisotropy can be achieved using only earth-abundant elements, the Georgetown team has shown a clear path toward more sustainable magnetic technologies. The implications stretch across applications that demand high anisotropy, from magnetic recording media and spintronic devices to energy-efficient permanent magnets that no longer depend on rare-earth elements.

Beyond the immediate applications, the work highlights something even larger. It reveals how much potential still lies hidden in complex materials that have barely been explored. By combining chemical creativity, advanced synthesis techniques, and theoretical insight, the researchers have opened a door to a future where high performance no longer requires scarce resources.

In a world increasingly shaped by the need for clean energy and resilient technologies, that shift is more than a scientific achievement. It is a quiet but profound step toward building the tools of tomorrow from materials that the Earth can readily provide.

Study Details

Willie B. Beeson et al, C16 Phase High Entropy Borides With High Magnetic Anisotropy, Advanced Materials (2025). DOI: 10.1002/adma.202516135