Cooling something down usually feels like a predictable journey. A gas settles into a liquid. A liquid stiffens into a solid. The story seems finished once everything freezes in place. But quantum matter has never been interested in following ordinary rules, and one of its strangest characters has been quietly challenging physicists for decades.

In the early 20th century, researchers discovered that helium, when cooled far enough, does not simply become another rigid solid. Instead, it turns into a superfluid, a state of matter that flows without losing energy. This bizarre fluid can move endlessly, slip through tiny spaces, and even crawl up the walls of its container as if gravity were optional. It is motion without friction, a liquid that refuses to slow down.

Yet the deeper mystery was not what helium became when it was cold, but what would happen if it became even colder. Would the motion persist forever, or could something stranger still emerge from the quantum fog?

For more than half a century, physicists have asked this question without finding a clear answer. Now, that long-standing puzzle may finally be cracking open.

A Moment When Motion Stops

In a paper published in Nature, a team led by Cory Dean of Columbia University and Jia Li of the University of Texas at Austin reports something extraordinary. They observed a superfluid that suddenly came to a standstill, undergoing what appears to be a phase transition into a completely different quantum state.

“For the first time, we’ve seen a superfluid undergo a phase transition to become what appears to be a supersolid,” Dean said.

The comparison he reached for was familiar and comforting. It was like water freezing into ice. Except this time, the transformation was not happening in everyday matter, but deep inside the quantum realm.

A supersolid is one of those ideas that sounds self-contradictory the moment you hear it. Classical solids are defined by order and stillness, their atoms locked into a repeating crystal lattice. Superfluids, by contrast, are defined by perfect motion. A supersolid is predicted to combine both traits at once, maintaining a crystalline structure while also allowing frictionless flow.

Physicists have debated whether such a state could truly exist in nature. While simulated versions have appeared in laboratories, no one had definitively seen a naturally occurring superfluid transform into a supersolid before.

Until now.

A Quantum Phase That Refused to Be Seen

The idea of supersolids has hovered over condensed matter physics like an unfinished sentence. Theoretically elegant, experimentally elusive. In helium and other materials, researchers kept looking, only to find ambiguity and controversy.

In recent years, scientists working in atomic, molecular, and optical physics managed to create systems that behaved like supersolids. But these relied on carefully engineered setups using lasers and periodic traps. The traps nudged the particles into crystal-like patterns, forcing order onto the fluid much like an ice cube tray shapes Jello. Impressive, but not spontaneous.

What physicists really wanted was to see a supersolid emerge on its own, without external scaffolding. A natural transition, written into the laws of quantum matter rather than imposed by experimental design.

That is where an unlikely hero entered the story.

The Surprise Power of a One-Atom-Thick Crystal

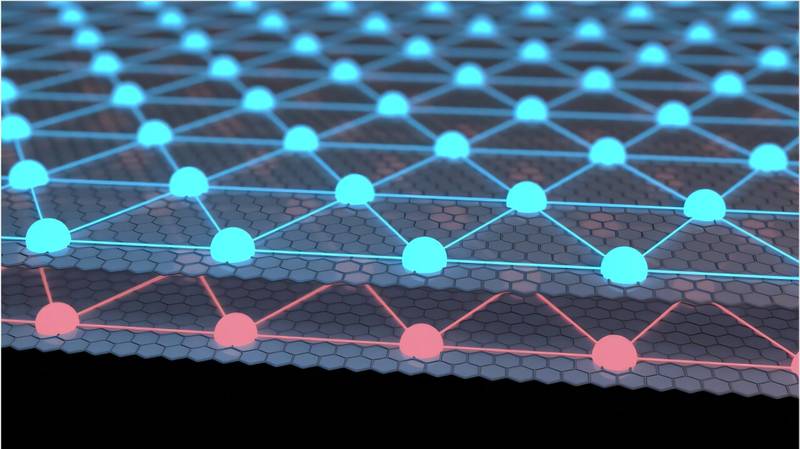

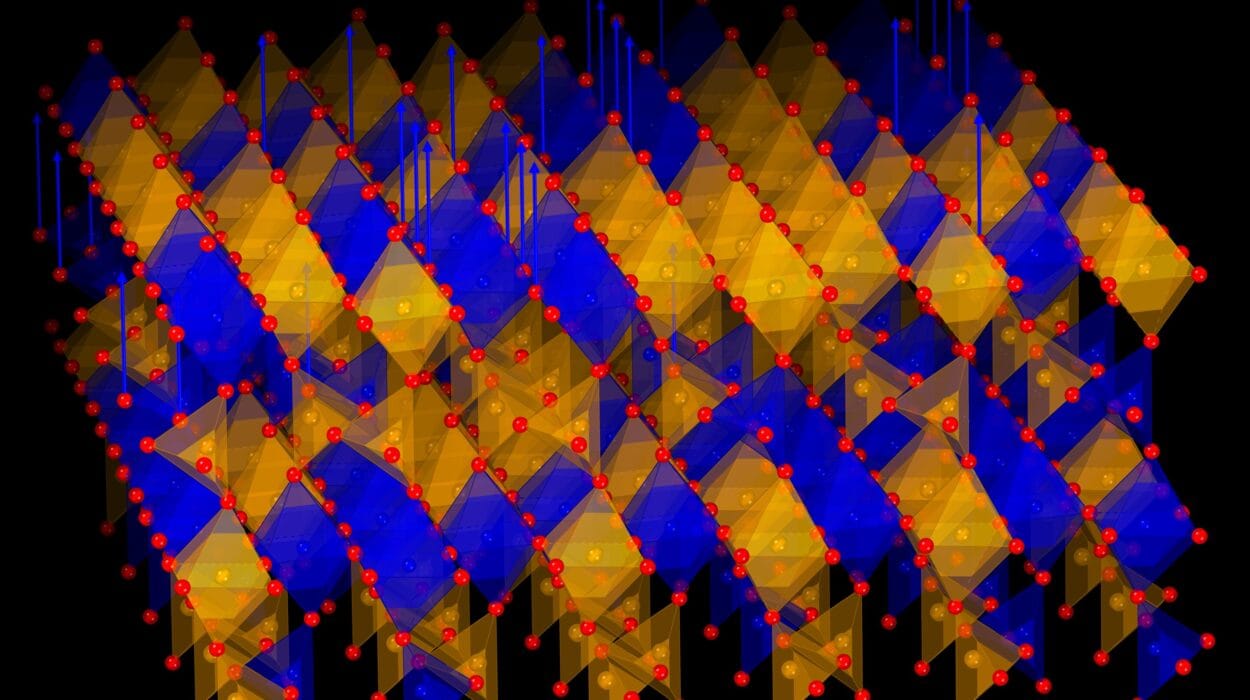

The team turned to graphene, a material famous for being only one atom thick and composed entirely of carbon. Though it looks simple, graphene has become a playground for exotic physics.

When two ultra-thin sheets of graphene are layered together and manipulated just right, something remarkable happens. One layer can be given extra electrons, while the other is left with holes, the positive counterparts created when electrons are removed by light. These oppositely charged particles can bind together, forming quasiparticles known as excitons.

Under the influence of a strong magnetic field, excitons can behave collectively, forming an excitonic superfluid. In this state, they move together without resistance, much like helium in its superfluid phase.

Graphene belongs to a broader family known as 2D materials, which have become powerful tools for exploring quantum phenomena. Researchers can adjust temperature, electromagnetic fields, and even the distance between layers, turning experimental knobs that allow them to fine-tune how particles interact.

This tunability set the stage for an unexpected discovery.

A Quantum State That Melted When Heated

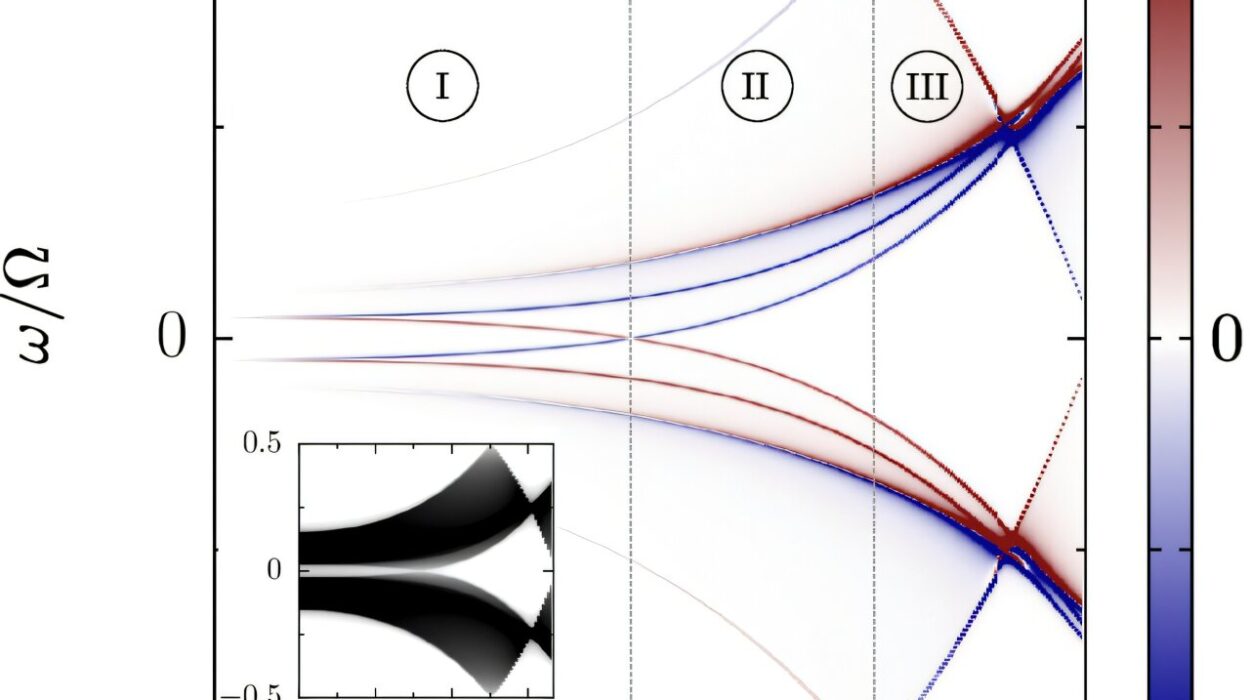

As the researchers carefully adjusted the properties of their graphene samples, they noticed something that made them stop and look again. The behavior of the excitons changed dramatically depending on their density and the temperature.

At high density, the excitons behaved exactly as expected, flowing freely as a superfluid. But when the density dropped, something astonishing happened. The particles stopped moving altogether. The system became an insulator.

Even stranger, when the team raised the temperature, the motion returned. The insulating phase melted back into a superfluid.

“Superfluidity is generally regarded as the low-temperature ground state,” Li explained. “Observing an insulating phase that melts into a superfluid is unprecedented.”

This reversal of expectations pointed toward something unusual hiding at low temperatures. The insulating phase was not simply a failure of superfluidity. It appeared to be a distinct quantum state, possibly an exciton solid.

The behavior fit the long-standing predictions of a supersolid, a phase that locks particles into a structure while preserving their quantum identity. Yet proving this conclusively remains challenging.

Standing at the Edge of What Can Be Measured

Despite the strong evidence, the team is cautious about making definitive claims. Their expertise lies in transport measurements, which rely on particles carrying current. Insulators, by their nature, do not transport current, making them difficult to probe directly.

“We are left to speculate some, as our ability to interrogate insulators stops a little,” Dean said.

For now, the researchers are mapping the boundaries around the insulating state, studying how it emerges and disappears as conditions change. At the same time, they are working to build new tools that could measure the state more directly and confirm whether it truly is a supersolid.

Science often advances this way, not through dramatic declarations, but by carefully narrowing the space where mystery can hide.

A Glimpse of Quantum Matter’s Future

The implications of this work stretch beyond a single experiment. The excitonic superfluid observed in bilayer graphene requires a strong magnetic field to exist, which limits its practical use. But the team is already exploring other layered materials that might host similar quantum states without that requirement.

These alternative systems are harder to fabricate, but they carry an enticing promise. Excitons are thousands of times lighter than helium atoms, meaning quantum states like superfluids and supersolids could potentially form at much higher temperatures.

If such states can be stabilized more easily, they could open entirely new directions in the study of quantum matter. What was once confined to extreme cold and exotic setups might become accessible in more flexible and controllable materials.

Why This Discovery Matters

For decades, the supersolid has existed as a theoretical possibility and an experimental tease. It represented a missing chapter in our understanding of how matter behaves when quantum rules dominate. This new work provides the strongest evidence yet that such a phase can arise naturally, without being forced into existence by external traps.

Beyond settling an old debate, the research shows the power of 2D materials as platforms for discovering new quantum phases. Graphene, already celebrated for its simplicity and strength, has revealed yet another hidden depth.

Understanding how superfluids can freeze into ordered, insulating states while retaining quantum character reshapes how physicists think about motion, order, and temperature. It reminds us that the quantum world does not merely extend the familiar rules of matter. It rewrites them.

In the quiet stillness of an insulating phase, born from a fluid that once flowed forever, physicists are finding answers to questions that have waited half a century to be asked the right way.

Study Details

Jia Li, Observation of a superfluid-to-insulator transition of bilayer excitons, Nature (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09986-w. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09986-w