In the very first instants after the universe began, there were no atoms, no protons, no neutrons, and no familiar building blocks of matter. Instead, everything existed as a seething, trillion-degree-hot mixture of quarks and gluons, moving at nearly the speed of light. This extreme state of matter is known as quark-gluon plasma, and it filled the newborn cosmos for only a few millionths of a second before cooling into the particles that make up everything we see today.

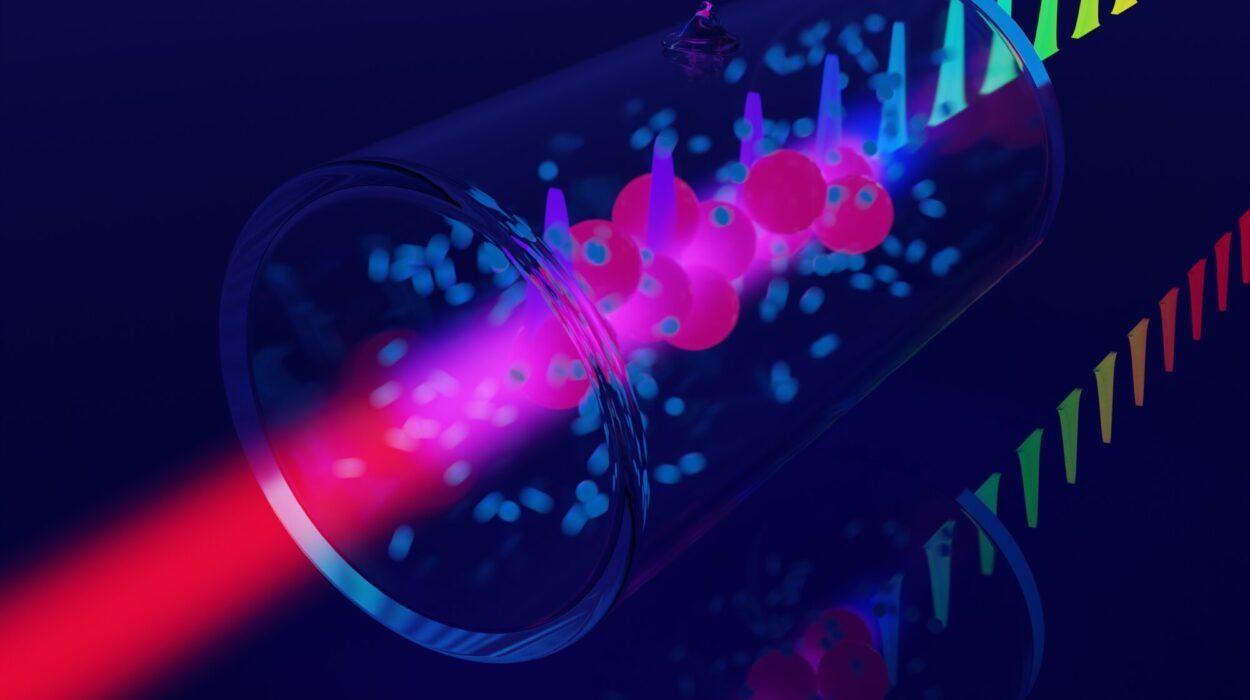

That fleeting moment is long gone, but physicists have been chasing it ever since. At CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, scientists recreate tiny droplets of this primordial material by smashing heavy ions together at extraordinary speeds. Each collision produces a short-lived flash of the same substance that once flooded the early universe. For a brief instant, researchers get to watch matter as it existed at the dawn of time.

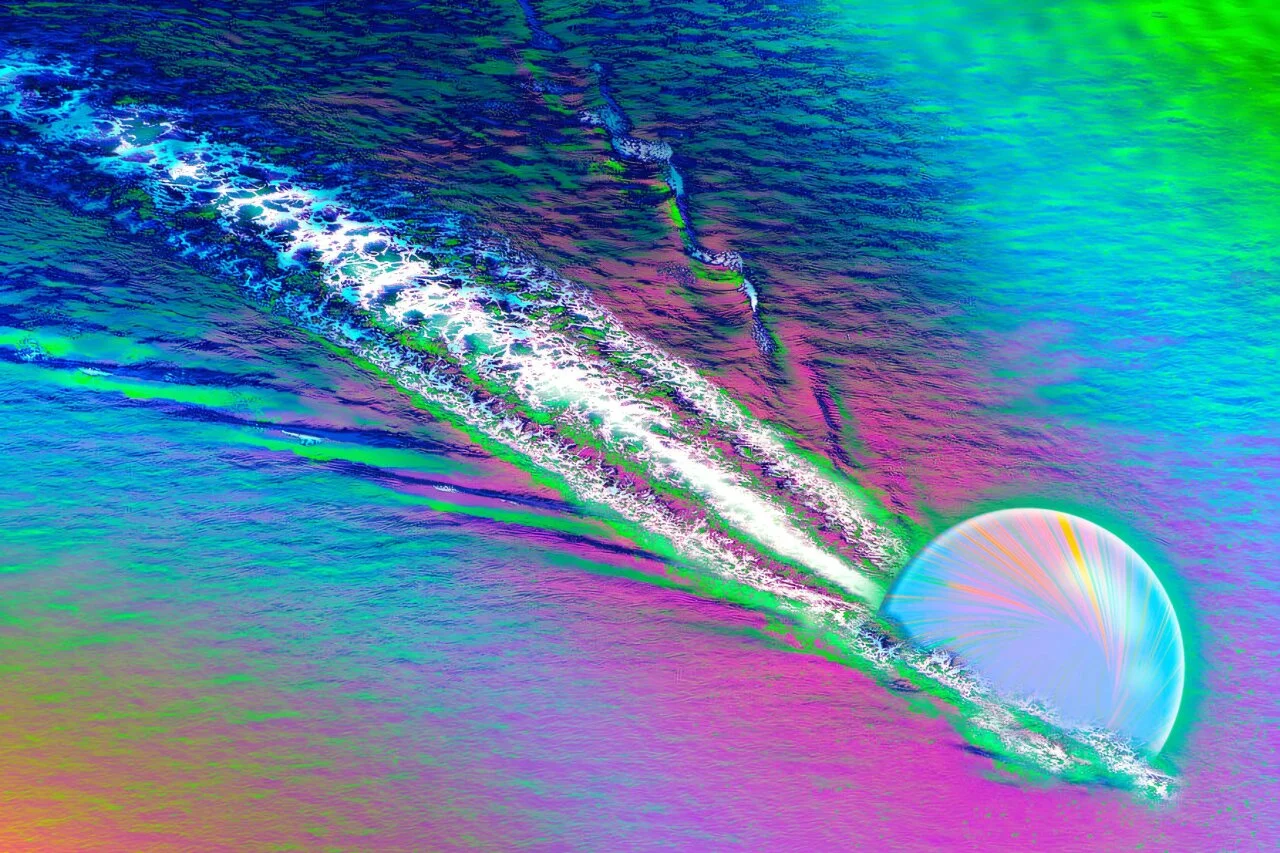

Now, a team led by physicists at MIT has found something remarkable within those flashes. They have observed clear evidence that quarks moving through quark-gluon plasma leave behind wakes, rippling trails similar to the patterns a duck leaves behind as it glides across water. The finding reveals, more directly than ever before, that this ancient matter behaves not like a chaotic spray of particles, but like a single, flowing liquid.

A Soup That Flows, Not Shatters

For years, scientists have suspected that quark-gluon plasma is unlike anything else in nature. It is thought to be the first liquid that ever existed in the universe, and also the hottest liquid ever known, reaching temperatures of a few trillion degrees Celsius. Despite that unimaginable heat, the plasma appears to flow smoothly, with its quarks and gluons moving together as if part of a nearly perfect fluid.

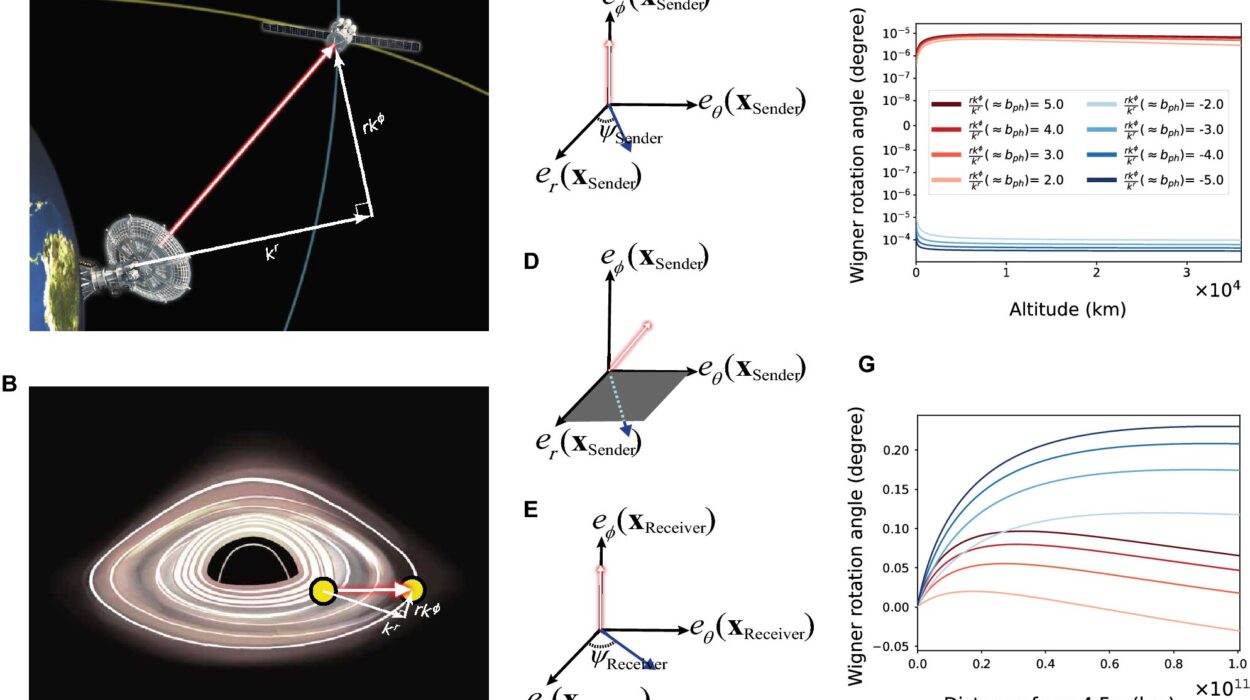

This idea did not emerge from a single experiment. It has been built gradually, supported by many observations and theoretical models. One of those models, developed by Krishna Rajagopal and his collaborators, predicts that quark-gluon plasma should react collectively when something plows through it. Instead of particles scattering independently, the plasma should respond as a whole, rippling and splashing around the intruder.

But seeing this effect directly has proven extremely difficult. The droplets of plasma created at the Large Hadron Collider exist for less than a quadrillionth of a second. Physicists can only take snapshots of their final state and work backward, searching for subtle patterns that hint at what happened inside.

For a long time, the evidence remained indirect. The question lingered: does the plasma truly behave like a fluid when struck by a fast-moving quark, or does it merely appear that way?

The Problem of Hidden Ripples

One major obstacle stood in the way of a clear answer. In high-energy collisions, quarks are usually produced in pairs, along with their counterparts known as antiquarks. These pairs shoot off in opposite directions at the same speed. If each particle creates a wake, those wakes can interfere with each other, blurring the signal physicists are trying to detect.

“When you have two quarks produced, the problem is that the wake of one can overshadow the wake of the other,” explains Yen-Jie Lee, a professor of physics at MIT and a lead author of the study. The overlapping effects make it extremely difficult to isolate the response of the plasma to a single quark.

To truly see how quark-gluon plasma reacts, the researchers realized they needed a cleaner scenario. They needed a way to track one quark moving through the plasma without a second one muddying the waters.

That realization led them to a different kind of particle entirely.

The Silent Partner That Leaves No Trace

Instead of searching for quark–antiquark pairs, Lee and his colleagues looked for collisions that produced a quark alongside a Z boson. A Z boson is an elementary particle that interacts very weakly with its surroundings. It carries no electric charge and passes through the quark-gluon plasma without disturbing it.

Crucially, Z bosons are produced at a very specific energy, making them relatively easy to identify in the complex aftermath of a collision.

“In this soup of quark-gluon plasma, there are countless quarks and gluons colliding,” Lee explains. “Sometimes, when we are lucky, one of these collisions produces a Z boson and a quark with high momentum.”

When that happens, the two particles fly off in opposite directions. The quark barrels through the plasma, while the Z boson slips away silently, leaving no wake at all. Whatever disturbance appears opposite the Z boson’s path must have been caused by the quark alone.

The team realized they could use the Z boson as a kind of tag, a marker that tells them exactly where to look for a quark’s wake.

Thirteen Billion Collisions and a Hidden Pattern

To test their idea, the researchers turned to data from the CMS experiment, one of the major particle detectors at the Large Hadron Collider. They sifted through an enormous dataset containing 13 billion heavy-ion collisions.

Out of all those events, they identified about 2,000 collisions that produced a Z boson. For each of these rare moments, they mapped how energy was distributed throughout the tiny droplet of quark-gluon plasma created by the collision.

Again and again, they saw the same striking pattern. On the side opposite the Z boson, the plasma showed signs of swirls and splashes, a fluid-like wake extending from the path of the quark. These patterns were not random. They were consistent, directional, and unmistakably tied to the quark’s motion.

For the first time, physicists could point to a clear, unambiguous signature of a single quark dragging the plasma along with it as it traveled.

A Theory Comes to Life

Even more compelling was how closely the observed wakes matched predictions from Rajagopal’s hybrid model. The size, shape, and behavior of the disturbances aligned with what the theory said should happen if quark-gluon plasma truly behaves as a fluid.

“This is something that many of us have argued must be there for a good many years,” Rajagopal says. “What this measurement has done is bring us the first clean, clear evidence for this foundational phenomenon.”

Other physicists echoed that sentiment. Daniel Pablos, a collaborator of Rajagopal’s, described the result as unambiguous proof that the plasma responds collectively, not as isolated particles.

For Lee and his team, the finding confirms a long-standing suspicion. The plasma is so incredibly dense that it can slow down a quark and respond with splashes and ripples, just like a liquid responding to an object moving through it.

“Quark-gluon plasma really is a primordial soup,” Lee says, one that sloshes and flows rather than shattering apart.

Taking a Snapshot of the Beginning

With this new technique, researchers now have a powerful way to probe the properties of quark-gluon plasma in much greater detail. By measuring the size, speed, and extent of quark wakes, and by studying how long those wakes take to fade away, scientists can learn more about the plasma’s internal structure.

Each wake is like a fingerprint, carrying information about how this exotic fluid behaves under extreme conditions. By analyzing many such fingerprints, physicists hope to build a clearer picture of what the universe was like during its first microseconds.

“With this experiment, we are taking a snapshot of this primordial quark soup,” Lee says.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research matters because it brings us closer to understanding the earliest moments of the universe, when matter existed in its most fundamental and extreme form. Quark-gluon plasma is not just an abstract concept. It is the state from which all protons, neutrons, atoms, stars, and galaxies ultimately emerged.

By showing that this plasma behaves like a flowing liquid, scientists gain crucial insight into how the universe cooled and organized itself into the structures we see today. The discovery also strengthens confidence in theoretical models that describe matter under conditions far beyond anything achievable on Earth.

Most importantly, the observation of quark wakes transforms a long-standing debate into a measurable reality. It reveals that even in the most violent, short-lived environments imaginable, nature can behave in surprisingly familiar ways. In the heart of a trillion-degree fireball, the universe once flowed like a liquid, leaving ripples that scientists are only now beginning to see.

Study Details

The Cms Collaboration, Evidence of medium response to hard probes using correlations of Z bosons with hadrons in heavy ion collisions, Physics Letters B (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.physletb.2025.140120