Near Waitomo on Aotearoa’s North Island, a quiet cave has been holding its breath for a million years. Long before people walked these forests, long before stories were told aloud, layers of ash settled, time slowed, and the remains of vanished lives were sealed into darkness. Now, that silence has been broken.

Australian and New Zealand scientists have uncovered an extraordinary collection of fossils in this cave, revealing the bones of ancient wildlife unlike anything previously known from this period. For the first time, a large group of million-year-old fossils has been found in Aotearoa, including the remains of an ancient parrot that appears to be a long-lost ancestor of the iconic Kākāpō. The discovery opens a rare and intimate window into a lost world, showing not just what lived here, but how violently the land itself reshaped life long before humans arrived.

A Lost World Comes Into Focus

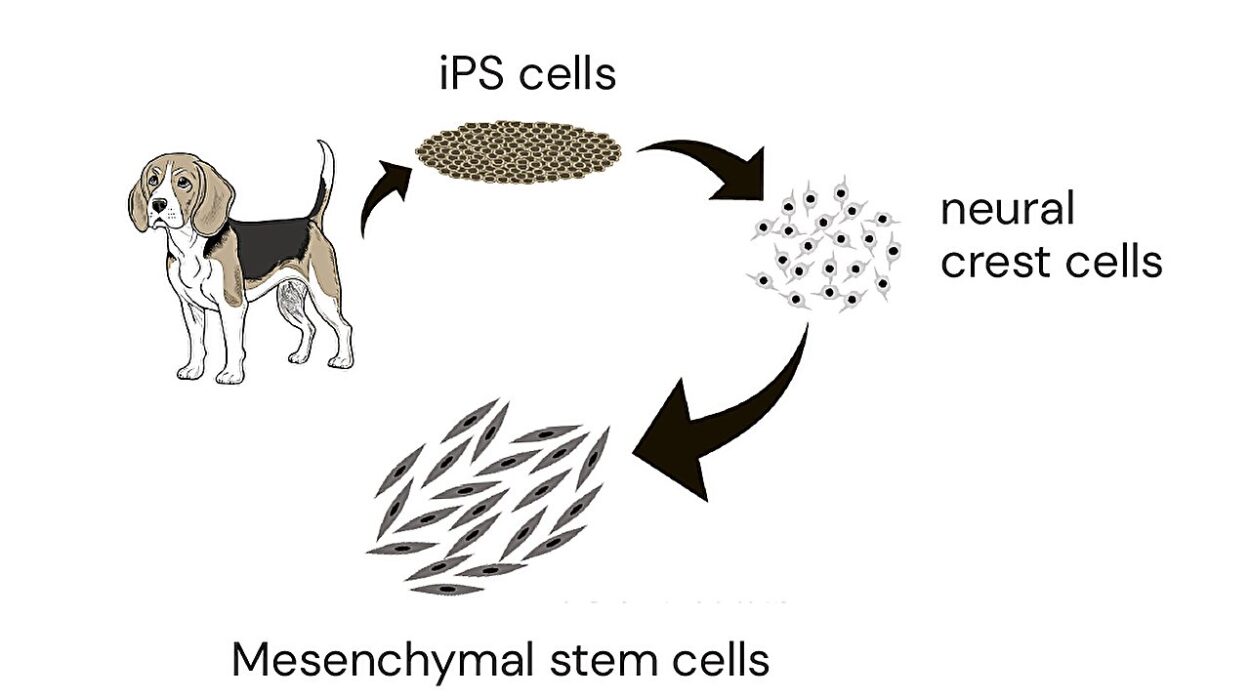

The fossils tell a story that had been missing almost entirely from New Zealand’s natural history. Researchers identified remains from 12 ancient bird species and four frog species, all dating back to around 1 million years ago. Until now, this era was little more than a blur, a gap between much older fossil sites and the ecosystems humans later encountered.

According to Associate Professor Trevor Worthy of Flinders University, this was not simply a missing chapter. It was, as he describes it, a missing volume. The birds preserved in the cave represent a newly recognized avifauna, one that thrived in ancient forests but did not survive into the later landscapes known to humans.

These forests were alive with diversity, yet fragile. The fossils suggest a dynamic ecosystem repeatedly tested by forces far beyond the control of any living creature. Climate shifts and volcanic eruptions reshaped habitats again and again, driving extinctions and replacing species in cycles that played out over hundreds of thousands of years.

When the Earth Itself Chose Survivors

The research, published in Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology, points to a striking conclusion. Between 33 and 50% of species went extinct in the million years before humans ever set foot in Aotearoa. These losses were not caused by hunting or habitat destruction, but by rapid climate changes and cataclysmic volcanic eruptions.

Dr. Paul Scofield, Senior Curator of Natural History at Canterbury Museum, explains that these findings help connect scattered fragments of the past. Previous excavations at St Bathans in Central Otago revealed life from 20 to 16 million years ago, but the long stretch between then and one million years ago was largely invisible in the fossil record. The Waitomo cave changes that, illuminating a turbulent period when landscapes were repeatedly erased and rebuilt.

Forests shifted, shrublands expanded or vanished, and bird populations were forced into constant adaptation. Each eruption or climate swing acted like a reset button, determining which species could survive and which would fade into history.

Meeting the Ancestor of a Living Legend

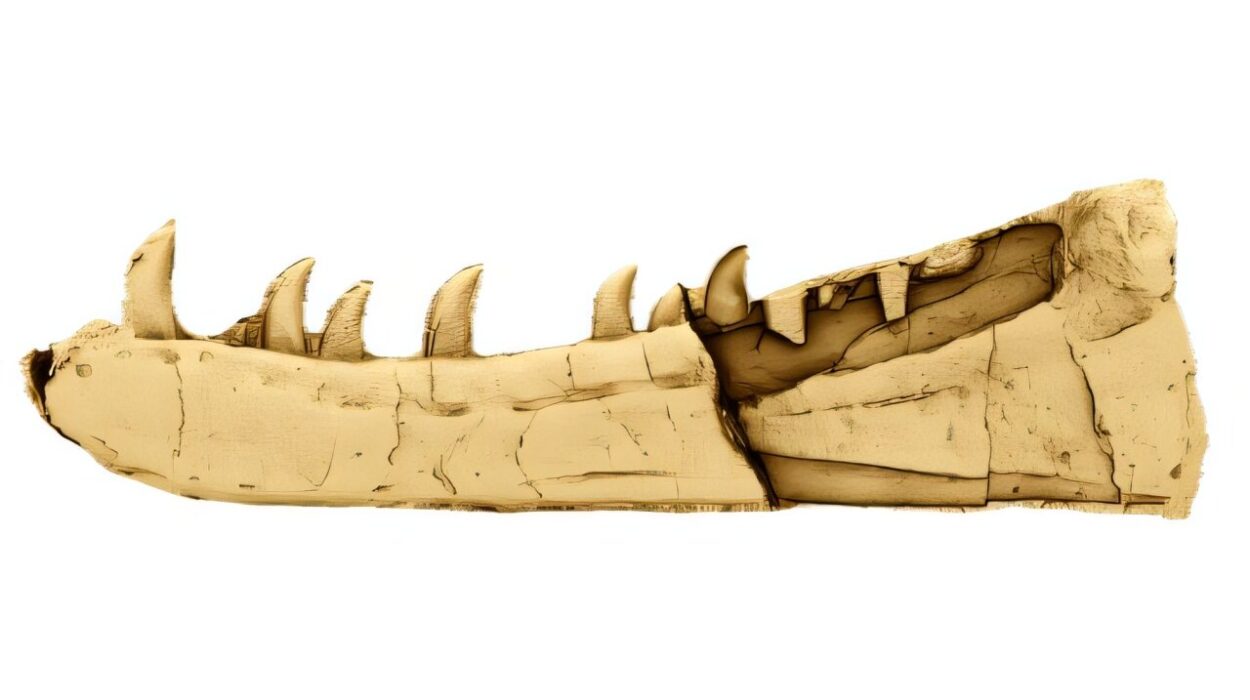

Among the most captivating discoveries is a new species of parrot named Strigops insulaborealis, an ancient relative of the modern Kākāpō. Today’s Kākāpō is famous for its heavy body and flightless life among forest floors. But this ancestor tells a more complicated story.

Fossil analysis suggests weaker legs than those of the modern bird, hinting that it may have been less skilled at climbing. That detail opens a tantalizing possibility. Unlike today’s Kākāpō, this ancient parrot may have been able to fly, though researchers stress that more evidence is needed to confirm this.

If true, it would mean that one of New Zealand’s most distinctive birds did not begin its evolutionary journey as a ground-bound giant, but as a more agile forest dweller, later reshaped by changing environments and repeated ecological upheaval.

Echoes of Other Familiar Birds

The cave did not preserve just one ancestral story. Researchers also identified an extinct ancestor of the modern Takahē, providing a rare chance to trace how this iconic bird evolved over deep time. Alongside it were the remains of an extinct pigeon species closely related to Australian bronzewing pigeons, hinting at connections and dispersals that once linked distant ecosystems.

Together, these fossils show a North Island alive with evolutionary experimentation. As habitats shifted between forest and shrubland, birds were forced to adapt, diversify, or disappear. According to Dr. Scofield, this constant pressure was a major driver of evolutionary diversification, shaping the unique wildlife that would later define Aotearoa.

Ash That Stopped the Clock

One of the most remarkable aspects of the discovery is how precisely the fossils could be dated. The cave acted as a natural archive, trapping remains between two distinct layers of volcanic ash. The older layer came from an eruption 1.55 million years ago, while the younger was deposited by a massive eruption around 1 million years ago.

That later eruption was so powerful it would have blanketed much of the North Island in meters of ash. Most of it eventually washed away, but inside caves like this one, the ash remained, sealing fossils in place. The presence of the older ash layer also confirms something extraordinary. This is the oldest known cave in the North Island, preserved not just as a shelter, but as a time capsule.

Rethinking Extinction in Aotearoa

For decades, discussions about extinction in New Zealand focused heavily on human arrival around 750 years ago. There is no question that humans had a profound impact. But this discovery forces a broader perspective.

Associate Professor Worthy emphasizes that natural forces were already shaping the fate of wildlife long before people appeared. Super-volcanoes and dramatic climate shifts were powerful sculptors, repeatedly redefining which species could endure. The cave fossils provide what he calls a critical missing baseline, allowing scientists to see how ecosystems changed naturally, without human influence.

Why This Discovery Matters Now

This research matters because it reshapes how we understand resilience, loss, and survival. It shows that extinction is not always sudden or singular, but often the result of long-term environmental stress. It reminds us that today’s wildlife carries the legacy of countless past upheavals, written into bone and stone.

By revealing a forgotten era of Aotearoa’s natural history, the Waitomo cave fossils deepen our understanding of how life responds to extreme change. They tell us that the landscapes we see today are not fixed, but the latest chapter in a long, volatile story. And in a world facing rapid environmental shifts once again, that perspective has never been more important.

Study Details

Trevor H. Worthy et al, The first Early Pleistocene (ca1 Ma) fossil terrestrial vertebrate fauna from a cave in New Zealand reveals substantial avifaunal turnover in the last million years, Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology (2026). DOI: 10.1080/03115518.2025.2605684