For most of modern science, electrons have been studied as individuals. We track their paths, measure their energies, and watch how they respond to light. Yet the true character of matter does not emerge from lonely particles. It emerges from relationships. Electrons influence one another constantly, forming fleeting patterns that decide whether a material conducts electricity, whether a molecule rearranges itself, or whether fragile quantum information survives or vanishes. Until now, these shared motions have remained largely hidden.

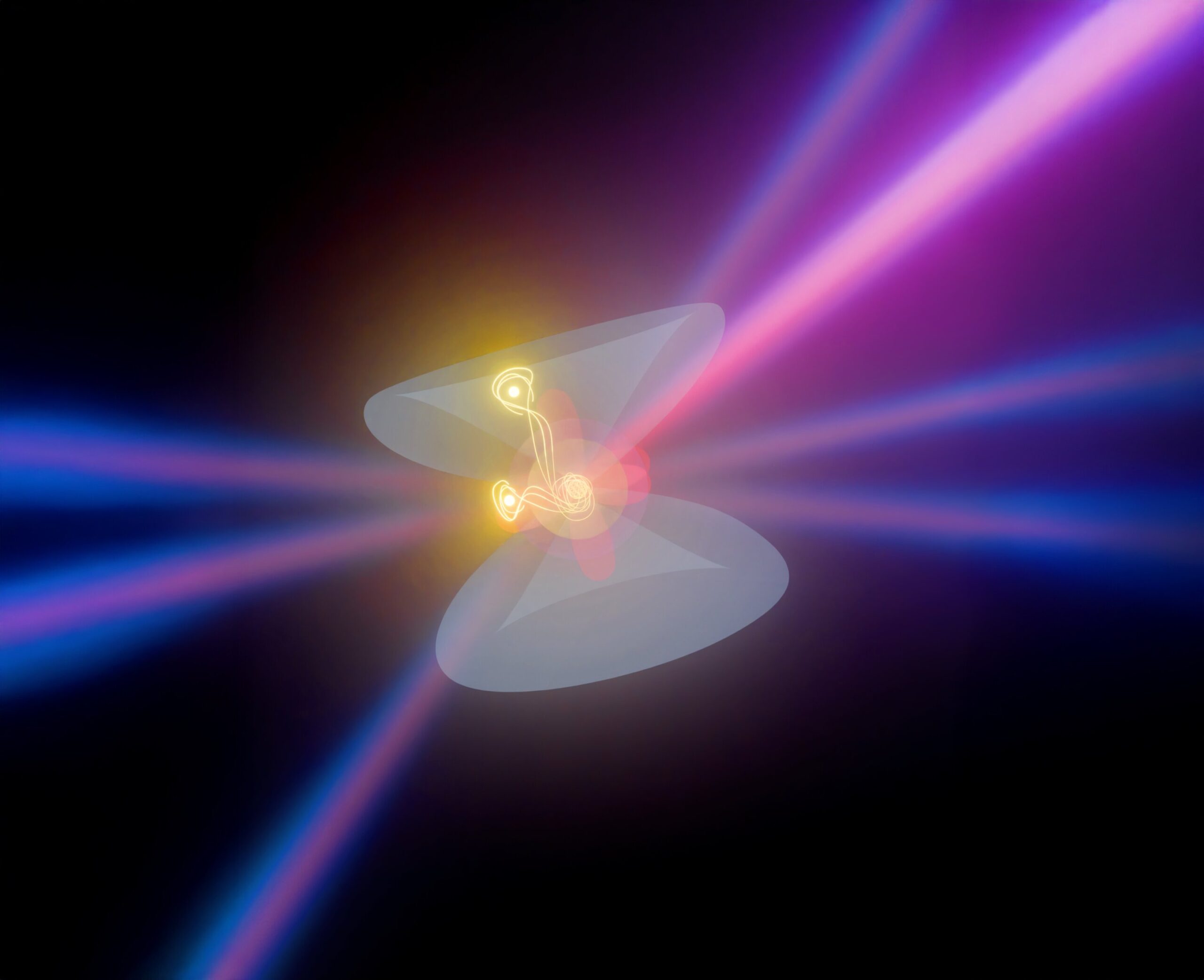

At the X-ray free-electron laser SwissFEL, scientists have finally opened a window onto this invisible world. Using a technique called X-ray four-wave mixing, they have achieved something physicists have pursued for decades: a direct experimental view of how electrons move together, how they share energy, and how they briefly lock into delicate states of coordination. The results, reported in Nature, mark a turning point in how we can observe the inner choreography of matter.

“We learn how the electrons dance with each other,” says Gregor Knopp, who led the study. “Whether they hold hands, or if they dance alone.” It is a poetic description of a deeply technical breakthrough, and it captures the heart of the discovery. For the first time, scientists are no longer blind to these collective quantum motions.

The Fragile Patterns Where Information Lives

Much of what we call matter is shaped not by electrons acting independently, but by the way they influence one another. In chemistry, these interactions determine how bonds form and break. In materials, they decide whether something insulates or conducts. In advanced technologies, they govern how energy flows and dissipates.

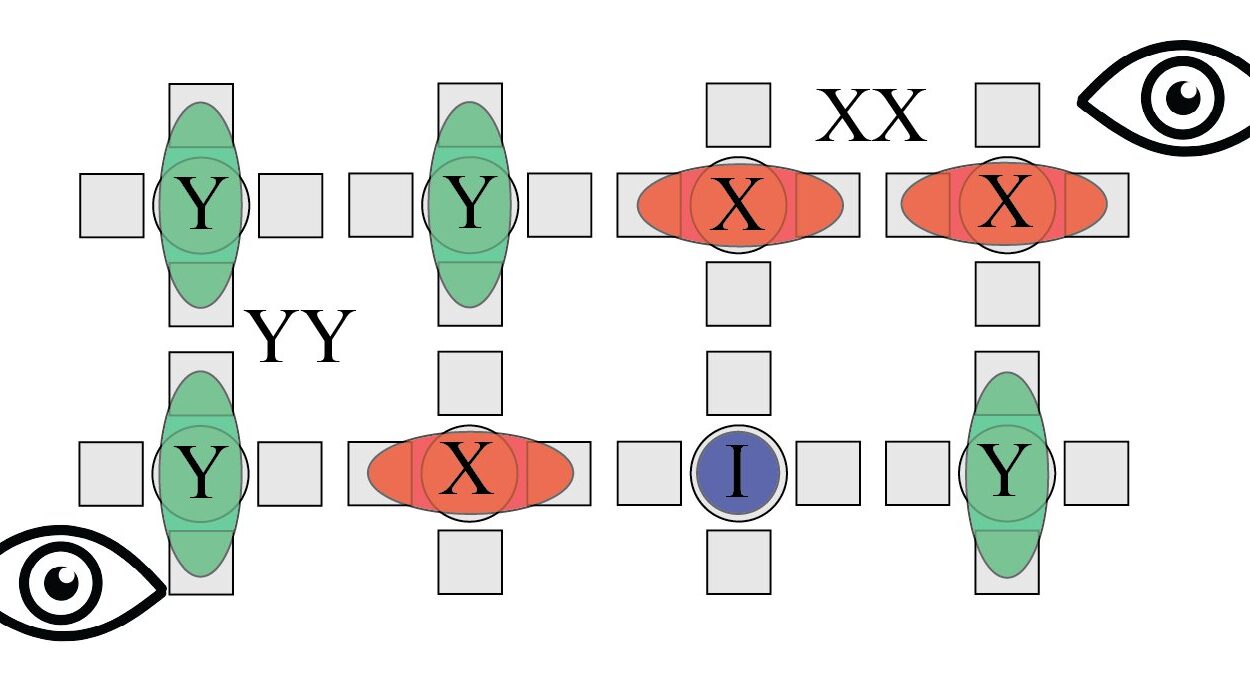

In the growing field of quantum technology, these interactions carry an even heavier burden. Quantum information is not stored in solid, durable objects, but in fragile patterns of electron interactions known as coherences. These coherences encode information in the synchronized behavior of particles. When they disappear, information disappears with them, through a process called decoherence.

Understanding how coherences form, evolve, and collapse is one of the central challenges facing quantum computing and related technologies. Many experimental tools can tell us what a single electron is doing, but they struggle to reveal how electrons behave together. As a result, the very states that matter most for quantum devices have remained elusive.

The work at SwissFEL changes that balance. By accessing these coherences directly, scientists can now watch how information flows through electrons and how it leaks away.

A Familiar Idea, Reborn with X-rays

At its core, X-ray four-wave mixing is not an entirely new idea. The concept has long existed in other forms of spectroscopy. It shares a family resemblance with nuclear magnetic resonance, the technique behind everyday MRI scans in hospitals. In both cases, multiple pulses are used to create and then read out coherent states in matter.

Four-wave mixing itself is already a well-established method using infrared and visible light. In those regimes, it has helped scientists explore how molecules vibrate, move, and interact. It has found applications in optical communication and biological imaging, offering rich information about how systems evolve over time.

What makes the SwissFEL achievement extraordinary is the leap into the X-ray domain. X-rays operate on a much smaller scale, directly probing electrons rather than entire atoms or molecules. “With X-rays we can zoom right in to the electrons,” explains Ana Sofia Morillo Candas, the first author of the study. Where other methods see the outlines of matter, this one reveals its internal structure in motion.

This shift opens the door to insights not only in quantum information, but also in fields as diverse as biology, solar energy, and battery materials, wherever electron interactions play a defining role.

An Experiment Long Thought Impossible

The idea of performing four-wave mixing with X-rays has existed for decades. Turning that idea into a working experiment, however, seemed almost impossible. The challenge lies in the extreme precision required.

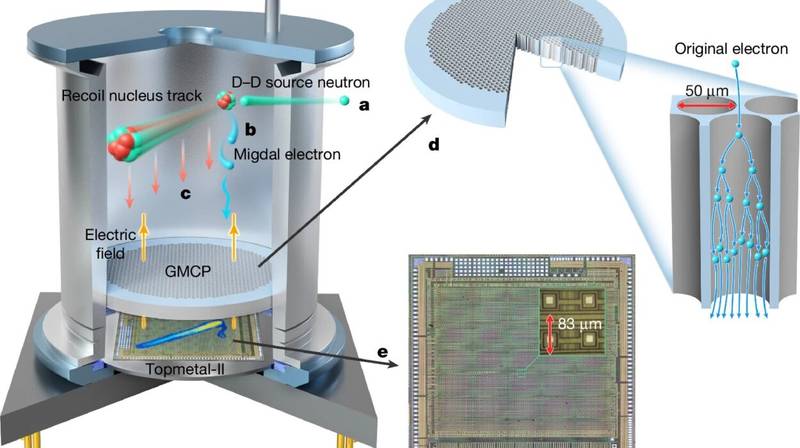

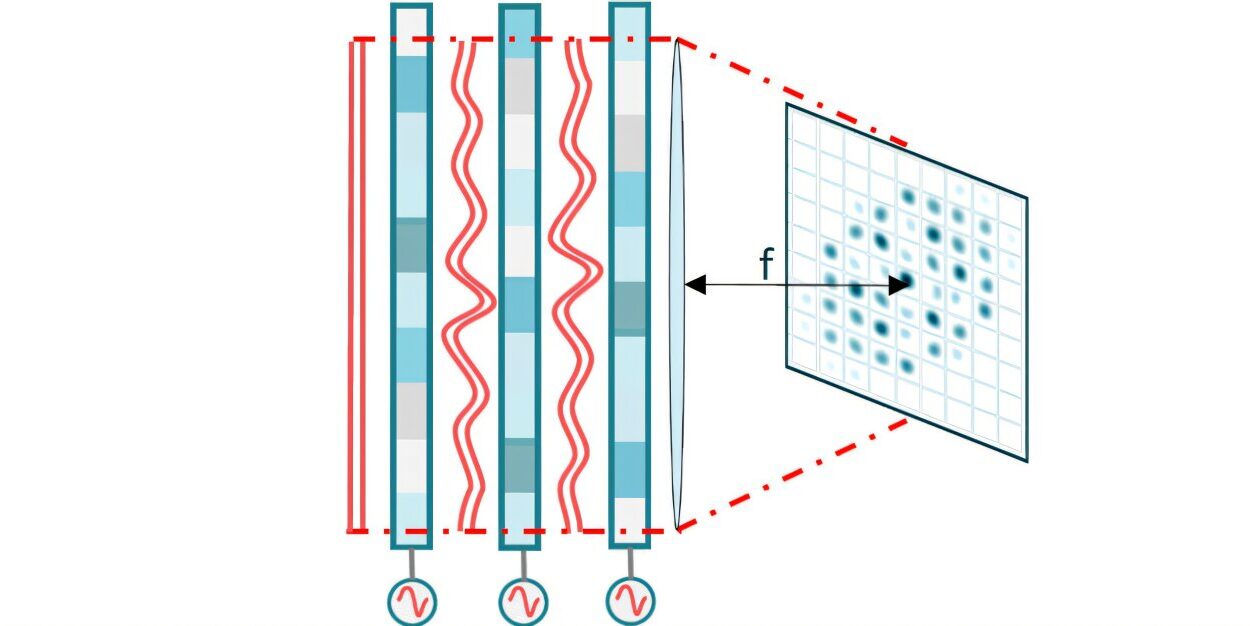

Four-wave mixing involves three incoming light waves interacting with matter to generate a fourth wave. To make this happen, scientists must split, delay, and recombine beams of light with extraordinary accuracy. With X-rays, whose wavelengths are incredibly short, even the smallest misalignment ruins the effect.

Morillo Candas describes the challenge simply: manipulating three X-ray beams is like throwing three darts from a kilometer away and having them land within nanometers of one another. Precision alone is not enough. The resulting signal is also astonishingly weak. Detecting it requires extremely bright and ultrashort bursts of X-ray light, something only facilities like SwissFEL can provide.

For years, this combination of difficulty and faintness kept the experiment in the realm of dreams. “Scientists have been dreaming about this experiment since SwissFEL was first built ten years ago,” Knopp says.

A Simple Trick That Changed Everything

The breakthrough did not come from adding complexity, but from stripping it away. The team borrowed a simple idea from experiments using ordinary laser light: an aluminum plate with four tiny holes.

Three X-ray beams pass through three of the holes. If four-wave mixing occurs, a new X-ray signal emerges at the position of the fourth hole. Conceptually, it is almost disarmingly simple. In optical experiments, this approach is standard. In the world of X-rays, it had not been seriously tried in this way.

To Knopp, who had experience with optical lasers, the solution felt obvious. To others, it was a gamble. When the team tested it, the result exceeded expectations. The signal was not barely detectable. It was striking.

A Glow in the Control Room

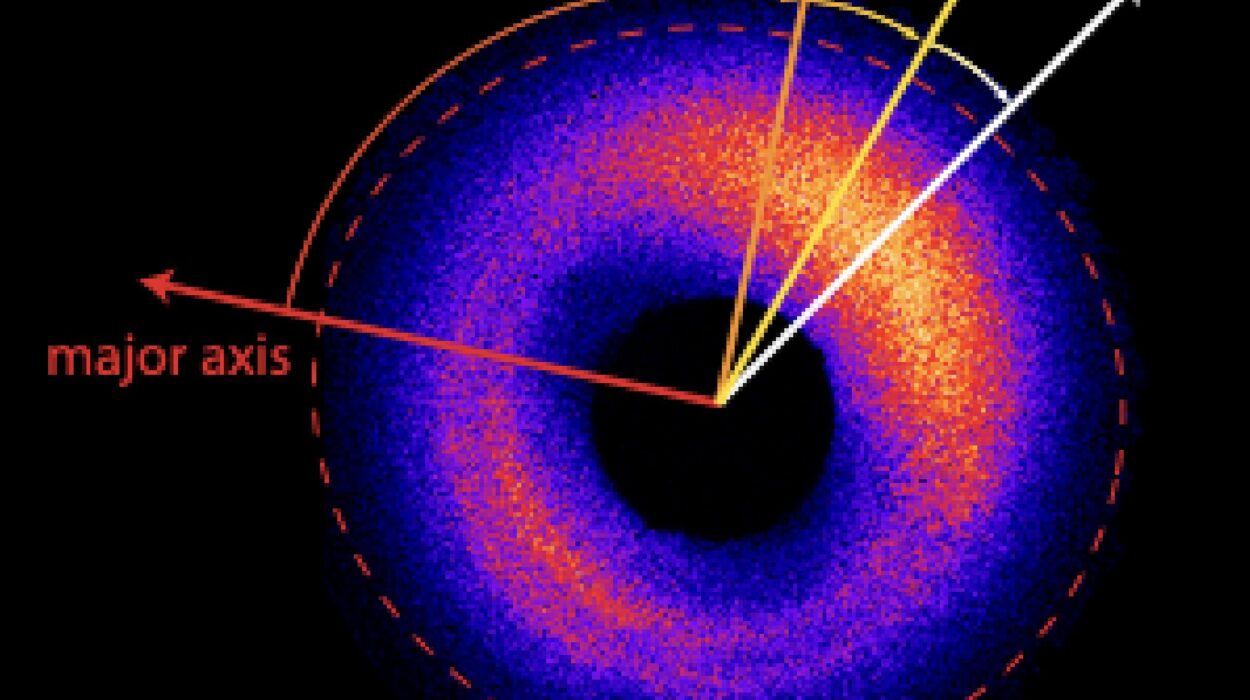

The moment of success arrived quietly, in the middle of the night. Morillo Candas was in the control room of the Maloja experimental station at SwissFEL when the signal appeared on the screen. To an untrained eye, it would have looked like almost nothing. To the scientists waiting for proof, it was unmistakable.

“It glowed like a light on the screen,” she recalls. The reaction was immediate and emotional. After years of theoretical anticipation and experimental frustration, the impossible had become real. They had seen the fourth wave.

That faint glow marked the first successful demonstration of X-ray four-wave mixing. It was the first time scientists had directly accessed electron coherences using X-rays.

Starting Simple, Looking Ahead

For this initial demonstration, the team chose neon, a noble gas with relatively simple electron behavior. Its lack of complicated interactions made it an ideal test system. If the signal could be seen there, it would confirm that the method worked.

Now that the proof of principle exists, the path forward is open. The researchers plan to move on to more complex gases, then to liquids and solids, where electron interactions become richer and more intricate. The simplicity of their approach, both Knopp and Morillo Candas believe, will help other scientists adopt and adapt the technique quickly.

What begins as a specialized experiment at a large facility could, over time, evolve into a widely used method.

Why This Breakthrough Matters

The deeper importance of X-ray four-wave mixing lies not in the elegance of the experiment, but in what it reveals. For the first time, scientists have a tool that can show where coherences live inside matter and where they break down. In other words, it can show where quantum information is stored and where it is lost.

This kind of insight is desperately needed. Today’s quantum devices struggle with errors caused by decoherence. Designers know the problem exists, but they lack a clear picture of how and where it happens at the level of electrons. X-ray four-wave mixing promises to provide that picture.

Knopp offers a historical comparison. In the 1960s, asking whether doctors could perform an NMR scan of a human knee would have seemed absurd. Yet it began with a first signal, faint and experimental. “This is where we are now,” he says.

If the future unfolds as he imagines, X-ray four-wave mixing could one day become a mainstream imaging technique for tiny quantum devices, revealing their inner workings with unprecedented clarity. By finally watching electrons dance together, scientists may learn how to keep their steps in sync—and how to protect the fragile information they carry.

Study Details

Ana Sofia Morillo-Candas et al, Coherent nonlinear X-ray four-photon interaction with core-shell electrons, Nature (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09911-1