For nearly a century, a quiet idea sat inside the pages of theoretical physics, waiting. In 1939, Arkady Migdal, a Soviet physicist, proposed a subtle consequence of violence at the smallest scale of matter. If an atomic nucleus were suddenly struck and jolted backward, the atom’s internal balance would shatter for a fleeting instant. The electric field holding its electrons in place would shift too quickly to remain stable, and one electron might be flung free.

It was an elegant prediction, fragile and elusive, like a whisper inside a storm. For decades, the Migdal effect remained just that: a theoretical possibility, discussed, cited, and believed, but never directly seen. The effect was expected to be extraordinarily rare and incredibly small, easily drowned out by cosmic rays and the constant hum of natural radiation. Many teams tried. None succeeded.

Until now.

A research team in China has captured the first direct experimental evidence of this long-predicted phenomenon, closing a chapter that has remained open for almost ninety years. Their result does more than confirm an old idea. It opens a new path into one of the deepest mysteries of modern science: dark matter.

Seeing the Unseeable Inside a Single Atom

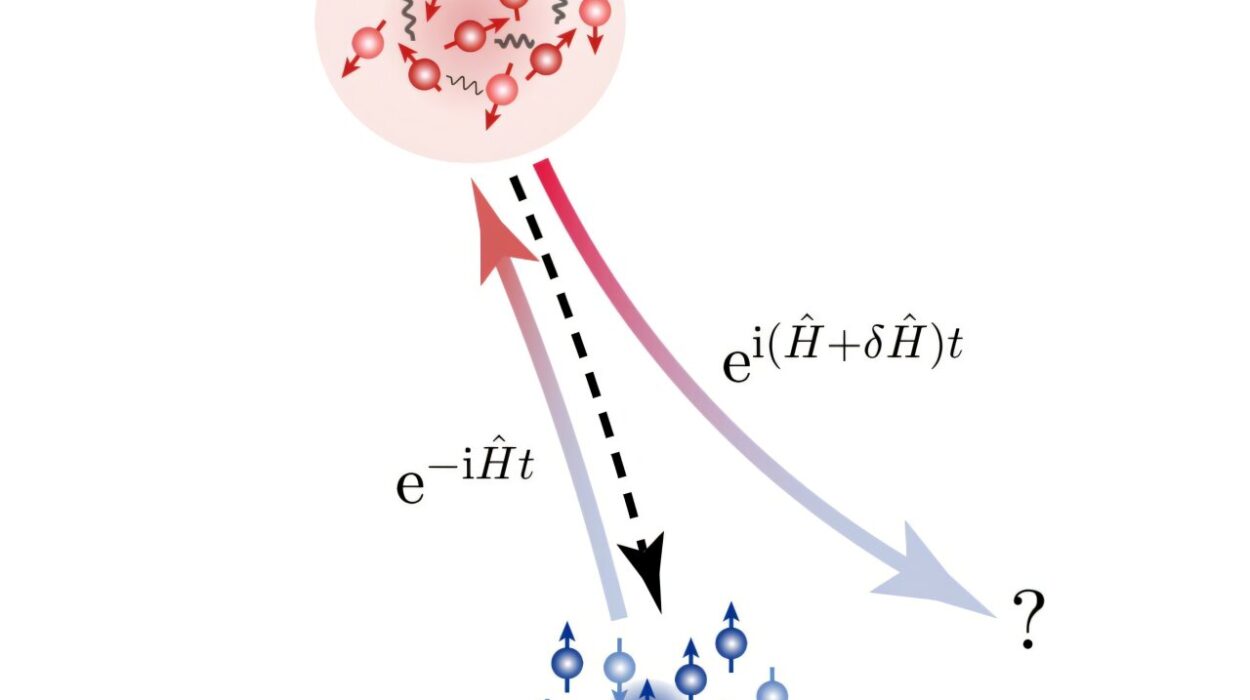

At the heart of the Migdal effect lies a dramatic moment. A neutral particle, such as a neutron or a possible dark matter particle, collides with an atomic nucleus. The nucleus recoils, snapping away from its original position. The electrons orbiting it suddenly find themselves bound to a moving center, and in that split second, the rules change. One electron may no longer remain attached. It escapes.

This ejected electron is the signature physicists have been hunting. But capturing it is like trying to photograph a lightning bolt inside a grain of sand.

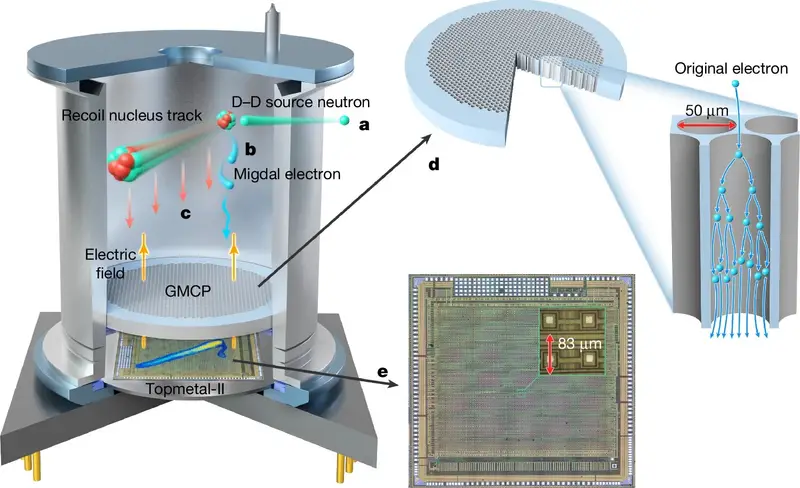

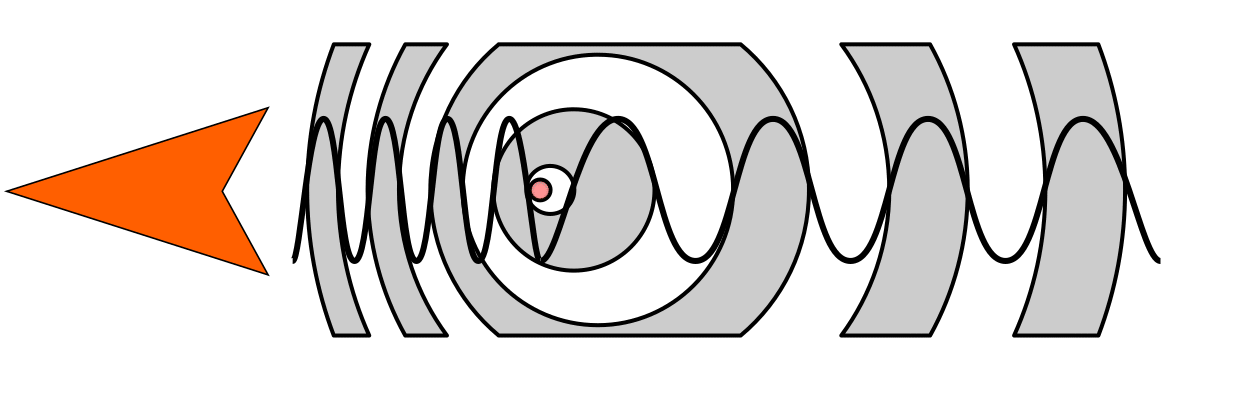

The Chinese research team, led by scientists at the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences and joined by several other universities, approached the problem with a bold idea. If the effect happens on a microscopic scale, the detector must be able to see with atomic precision. They built what they describe as an atomic camera, a highly sensitive gas detector integrated with a custom-designed microchip.

This instrument was not designed to merely count particles. It was built to track motion. It could follow the trajectory of a single recoiling atom and the path of a single escaping electron, tracing their movements through gas like invisible ink made suddenly visible.

To trigger the effect, the team bombarded gas molecules with neutrons. Then they waited, watching for a telltale sign: two particle tracks emerging from exactly the same point in space. One track would belong to the recoiling nucleus. The other would belong to the freed electron.

Eight Hundred Thousand Moments of Waiting

The experiment demanded patience on a staggering scale. The researchers analyzed more than 800,000 candidate events, each one a tiny burst of data representing a possible interaction. Most of them were noise. Some were near misses. Many were nothing at all.

Then, buried deep within the data, they found six events that stood apart.

Each of these six showed the unmistakable fingerprint of the Migdal effect. Two tracks, born together at the same location, diverging as expected. The nucleus recoiled. The electron escaped. No coincidence. No ambiguity.

The statistical confidence of the result reached five sigma, the gold standard of particle physics, meaning the chance of the signal being a random fluctuation is vanishingly small. This was not a hint. It was evidence.

For researchers who have chased this effect for decades, the moment carried enormous weight. Yu Haibo, a professor of physics and astronomy at the University of California, Riverside, described the achievement as a genuine breakthrough. He noted that several leading international teams had attempted to detect the Migdal effect in nuclear experiments without success. This result, he said, is truly exciting.

When an Old Idea Meets a Modern Mystery

The timing of this discovery is not accidental. Physics today stands at a crossroads in the search for dark matter, the invisible substance thought to make up roughly 85% of the universe. Its gravitational pull shapes galaxies and holds cosmic structures together, yet it does not emit, absorb, or reflect light. We know it is there because of what it does, not because of what we see.

For years, scientists focused their efforts on a popular class of hypothetical particles called WIMPs, or weakly interacting massive particles. These were expected to be heavy and rare, but detectable through the tiny recoils they would produce when colliding with atomic nuclei.

Major experiments put this idea to the test. Facilities such as PandaX in China and XENON in Italy searched carefully for these signals. They found none.

As the silence grew louder, attention began to shift toward a different possibility: light dark matter. These particles would be far lighter than WIMPs, and when they strike an atom, the energy they deposit would be so small that conventional detectors would barely notice.

This is where the Migdal effect becomes transformative.

Turning a Whisper Into a Signal

In a typical dark matter detector, the recoil of a nucleus caused by a lightweight particle is often too faint to register. The energy simply disappears below the threshold of detection. The event leaves no trace.

But the Migdal effect offers a clever detour around this limitation.

When an electron is ejected, it carries energy that detectors are much better at measuring. Zheng Yangheng, a professor at the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences and a co-leader of the study, explained that once an electron is freed, the detector can, in theory, capture 100% of its energy. The process converts an almost imperceptible nuclear jolt into a measurable electronic signal.

Instead of listening for the soft thud of a recoiling nucleus, scientists can watch for the sharper flash of an escaping electron. The Migdal effect acts as a translator, turning a silent interaction into something detectors can hear.

Liu Jianglai, a professor at Shanghai Jiao Tong University and lead scientist of the PandaX experiment, emphasized the importance of this step. He said the work fills a long-standing experimental gap and solidifies the theoretical foundation of the Migdal effect, marking a crucial first step toward applying it in the search for light dark matter.

A New Chapter Begins, Not an Ending

The discovery does not mean dark matter has been found. It does not guarantee that light dark matter exists. What it does is open a door that was previously locked.

The research team is already looking ahead. They plan to study the Migdal effect using different target materials, exploring how the phenomenon behaves in other elements. This is not a trivial detail. Understanding how often electrons are ejected and how much energy they carry is essential for designing future dark matter detectors.

Liu Qian, a professor at the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences and a co-leader of the research, explained that the next steps include optimizing the detector’s performance and extending observations to other elements. These measurements will provide essential data needed to support the search for even lighter dark matter particles.

Each refinement sharpens the lens. Each new material adds a piece to the puzzle.

Why This Discovery Truly Matters

At first glance, the Migdal effect might seem like a niche detail, a small correction inside atomic physics. But science often advances through such quiet revolutions.

This discovery confirms a prediction that stood untested for nearly ninety years, strengthening the bridge between theory and experiment. It demonstrates that even the most delicate ideas can be brought into the light with enough ingenuity and persistence.

More importantly, it equips physicists with a powerful new tool. In the ongoing search for dark matter, where the signals grow fainter and the questions deeper, the ability to detect what was once undetectable changes the landscape entirely.

The universe is mostly invisible. Its dominant matter does not glow, does not speak, and does not reveal itself easily. By capturing the fleeting escape of a single electron, scientists have shown that even the quietest interactions can leave a trace.

Sometimes, understanding the cosmos begins not with a thunderous discovery, but with learning how to hear a whisper.

Study Details

Difan Yi et al, Direct observation of the Migdal effect induced by neutron bombardment, Nature (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09918-8