In the tiny, unseen landscapes of quantum materials, particles lead surprisingly complex social lives. Their behavior is often dictated by a simple personality trait: whether they are introverts or extroverts. The extroverts, known as bosons, are the life of the party, happy to crowd together in a single shared quantum state to create wonders like superconductivity. The introverts, known as fermions, are the polar opposites. They refuse to share their personal space under any condition, a stubbornness that ironically provides the very structure needed for solid matter to exist.

Usually, these rules are set in stone. Electrons, which are fermions, either lock themselves away in an atom to create an insulator or roam independently to conduct electricity. Sometimes, they even form faithful couples known as Cooper pairs. But a team of researchers, led by JQI Fellow Mohammad Hafezi, recently decided to see what happens when you push these social boundaries to the limit. They wanted to know how a crowd of introverts would react to a group of extroverts, expecting that a sea of lonely fermions would act like a series of roadblocks, pinning the social bosons in place. Instead, they stumbled upon a quantum party where all the traditional rules of engagement were thrown out the window.

The Monogamy of the Quantum Couple

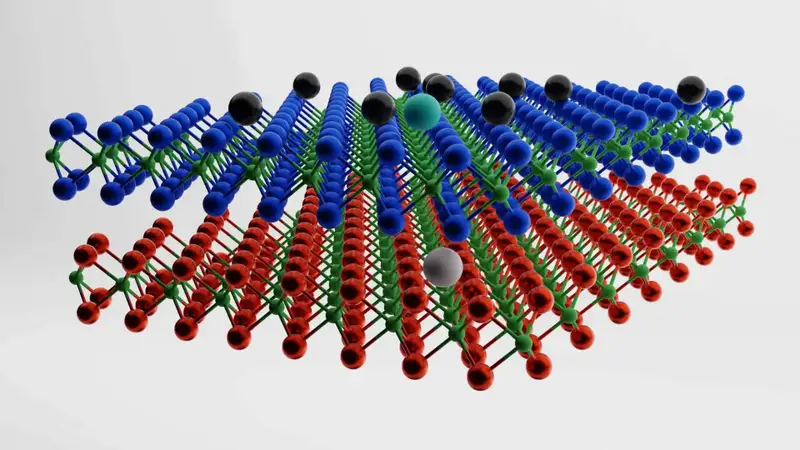

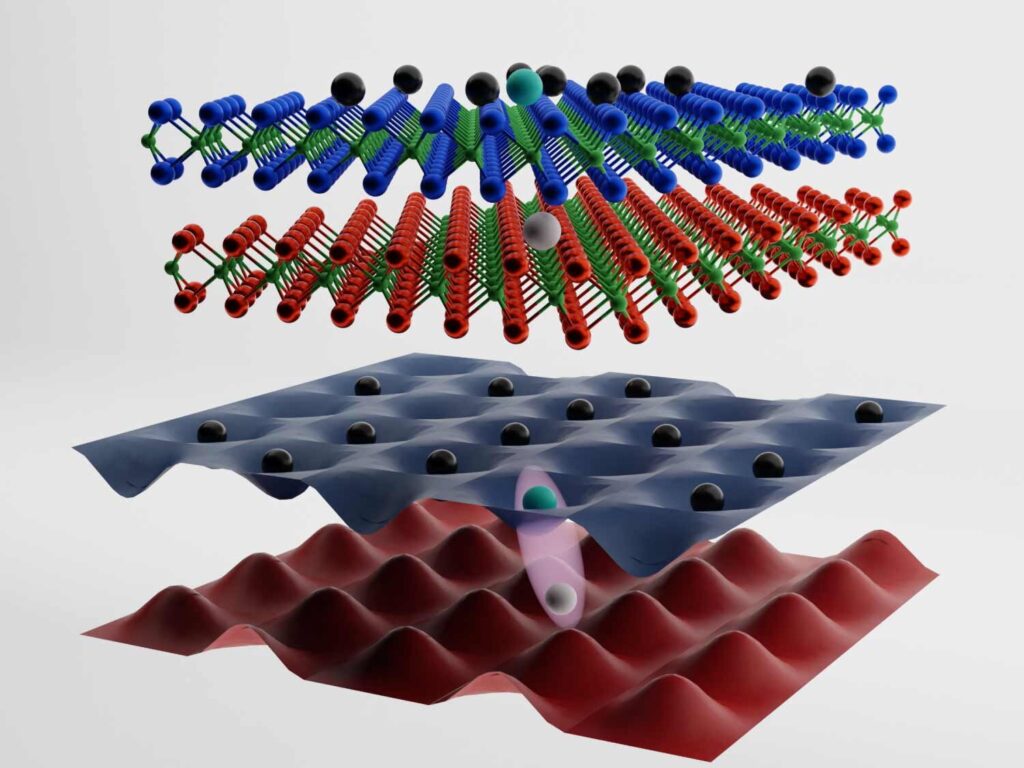

To understand the chaos that ensued, one must first meet the “exciton.” In the world of quantum physics, an exciton is a bit like a makeshift atom. It forms when an electron—a real particle—meets a “hole.” A hole isn’t actually a physical object; it is a quasiparticle, a disturbance created when a material is missing an electron, leaving behind a positive charge. While the hole can never leave its host material, it can move and carry energy.

When an electron and a hole find each other, they form a partnership. They move together as a single quantum object, and because it takes energy to pull them apart, they stay remarkably loyal. For years, physicists have referred to this relationship as monogamous. Because these pairs act as a single unit, the exciton is classified as a boson—an extrovert—while the unpartnered electrons surrounding them remain introverted fermions.

The researchers, including former JQI graduate student Tsung-Sheng Huang, assumed that any external fermion would see the exciton as a single, closed-off unit. They set up an experiment to test this, using a meticulously layered material that acted like a restaurant on Valentine’s Day. The floor was packed with tiny, intimate tables where only one particle or one couple could sit at a time. The plan was simple: fill the room with lone, introverted electrons and watch as the excitons struggled to navigate the crowded floor.

A Ghostly Sprint Through the Crowd

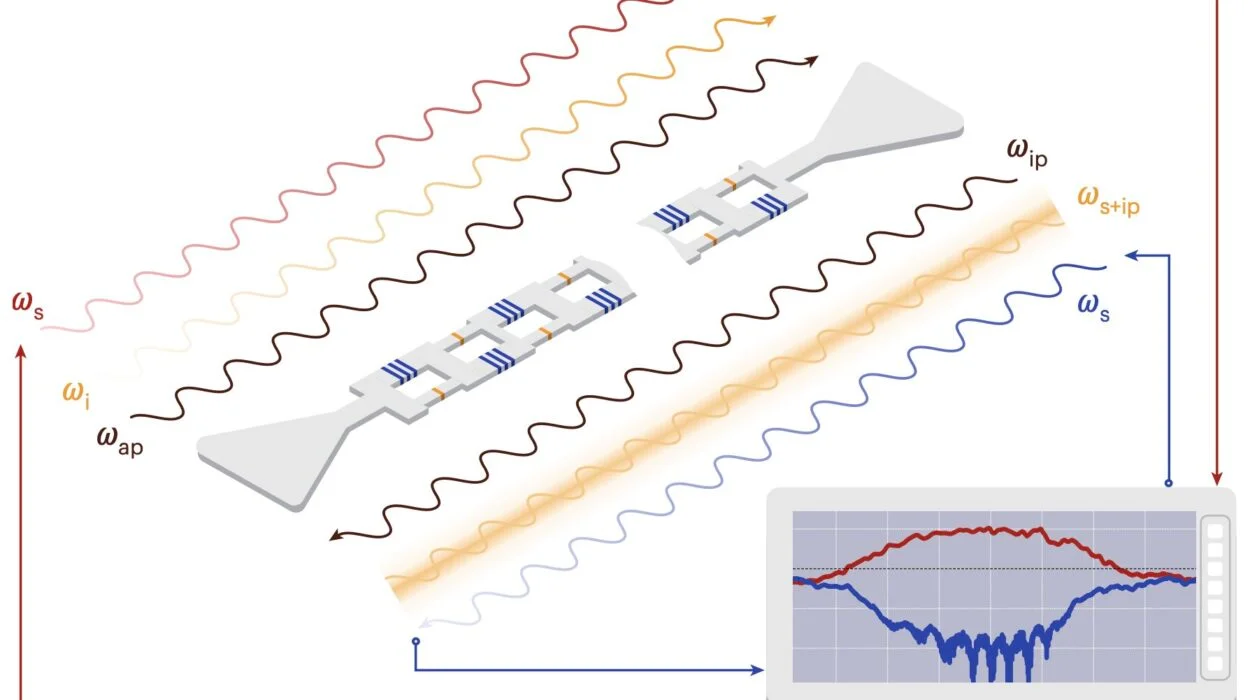

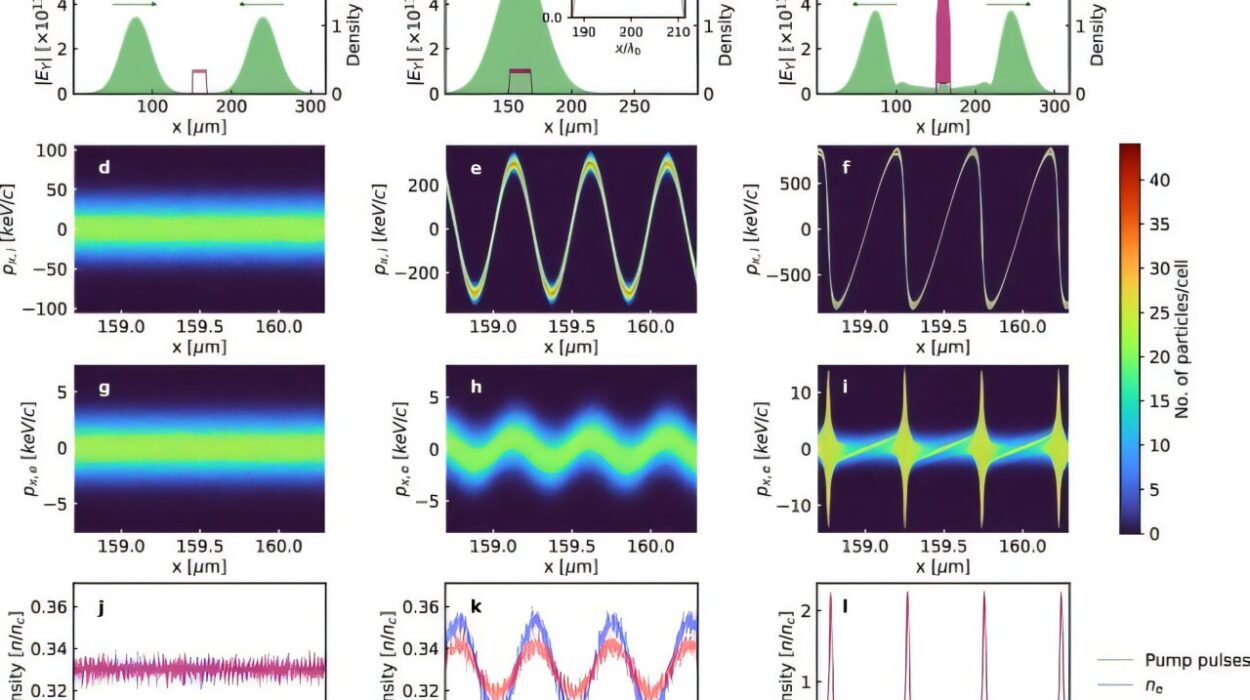

To control the guest list at this quantum gala, the team used electrical voltages to invite more electrons into the material and lasers to summon excitons. They expected that as they dialed up the number of lone electrons, the excitons would have a harder and harder time moving. At first, the physics behaved exactly as predicted. As the “tables” filled up with electrons, the excitons were forced to take long, winding detours, hopping from one empty spot to the next. Their movement slowed to a crawl.

But then, something impossible happened. Just as the room became so crowded that almost every table was occupied by a lone electron—a situation that should have frozen the excitons in place—the researchers saw a sudden, dramatic jump in mobility. Instead of stopping, the excitons began to move with incredible speed, traveling much farther than they ever had before.

“We thought the experiment was done wrong,” recalls Daniel Suárez-Forero, a former JQI postdoctoral researcher. “That was the first reaction.” The result was so counterintuitive that the team spent a month repeating the measurements across different samples. They even moved the experiment to a different lab on a different continent, traveling to the University of Geneva to see if the results would change. They didn’t. No matter where they went, the introverts weren’t blocking the extroverts anymore; somehow, the crowd was making the excitons move faster.

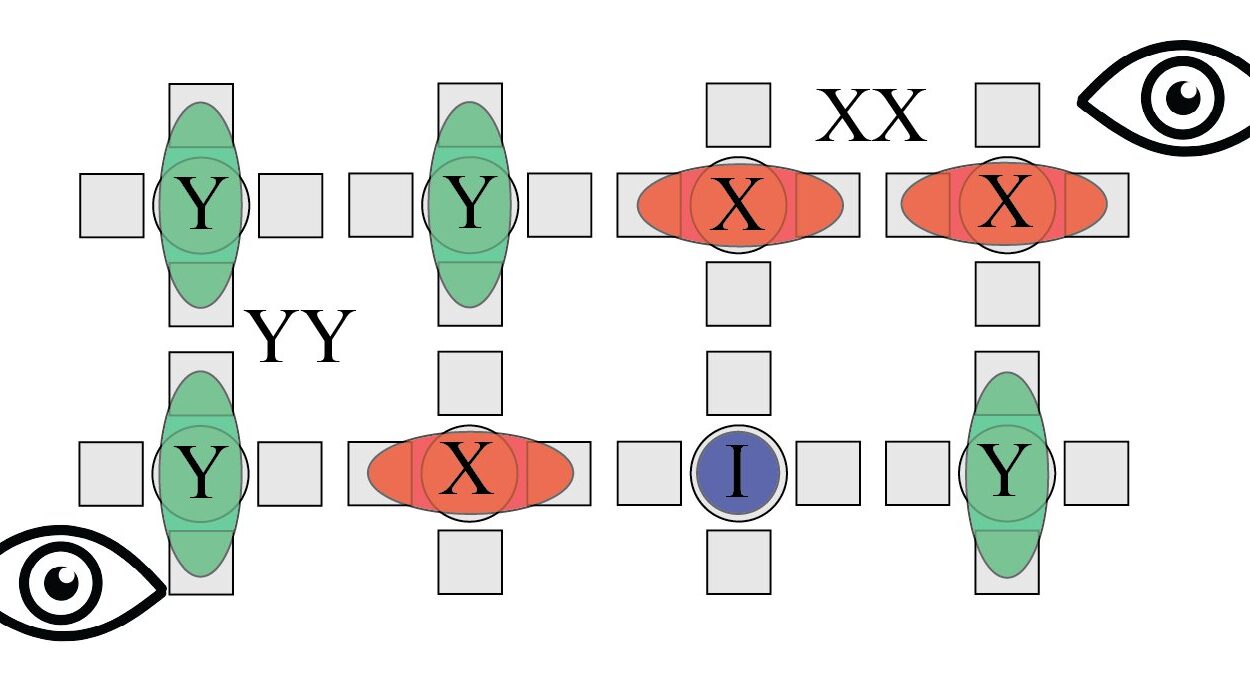

The Breakdown of the Social Contract

The mystery sat unsolved for months as the experimentalists huddled with theorists to find a flaw in their math. “We spent months going back and forth with theorists, trying out different models, but none of them captured all our experimental observations,” says Pranshoo Upadhyay, a JQI graduate student and the lead author of the study. The turning point came when they realized they had been thinking about the excitons all wrong. They had assumed the couples were “monogamous,” but the extreme conditions of the experiment had turned them into something else entirely.

The team realized that when the room became lopsided—flooded with an overwhelming number of available electrons—the holes in the excitons stopped being loyal. To a hole, one electron looks just like any other. In a sparsely populated room, the hole stays with its partner because there are no other options nearby. But in a room where every table has a new electron, the hole enters a “speed dating” round.

Instead of an exciton taking a winding path around the occupied tables, the hole simply ditches its current electron partner and grabs the one at the very next table. By constantly swapping partners, the hole can move in a straight line, making a beeline through the crowd. This “non-monogamous hole diffusion” allowed the excitons to reach their destinations much faster than if they had remained faithful to a single partner. They were essentially “ghosting” their way through the material by treating the sea of introverts as a series of stepping stones.

Why the Quantum Swap Matters

This discovery, published on Jan. 1, 2026, in the journal Science, is more than just a quirky observation of particle behavior. It represents a new way to manipulate how energy and information move through a material. Because the researchers could trigger this sudden sprint simply by adjusting the voltage, the technique is highly practical.

“Gaining control over the mobility of particles in materials is fundamental for future technologies,” says Suárez-Forero. By understanding how to break the rules of particle monogamy, scientists can design more efficient solar panels, where excitons must travel quickly to be converted into electricity. It also opens the door for a new generation of electronic and optical devices that can be “switched” into high-mobility states on demand. By mastering the social lives of these particles, researchers are finding that the best way to get ahead is sometimes to leave the old rules behind.

More information: Pranshoo Upadhyay et al, Giant enhancement of exciton diffusion near an electronic Mott insulator, Science (2026). DOI: 10.1126/science.ads5266. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2409.18357