Fifty-six million years ago, the planet was already warm. Not gently warm, but lush and green, wrapped in forests that reached far into places we now think of as cold and distant. Coniferous trees spread across high latitudes, storing vast amounts of carbon in their trunks, needles, and soils. The Earth had settled into a steady rhythm of warmth and life.

Then something happened.

In a geologically brief moment, a massive pulse of CO2 surged into the atmosphere. The climate warmed rapidly, by about five degrees, and the planet’s balance tipped. Forests burned. Soil broke loose. Land bled into the sea. What followed was not a slow adjustment, but a violent ecological shock that unfolded in centuries and echoed for thousands of years.

This story, buried beneath the waves of the Norwegian Sea, has now been brought back to light by microscopic traces locked inside ancient sediment.

A Silent Archive Beneath the Norwegian Sea

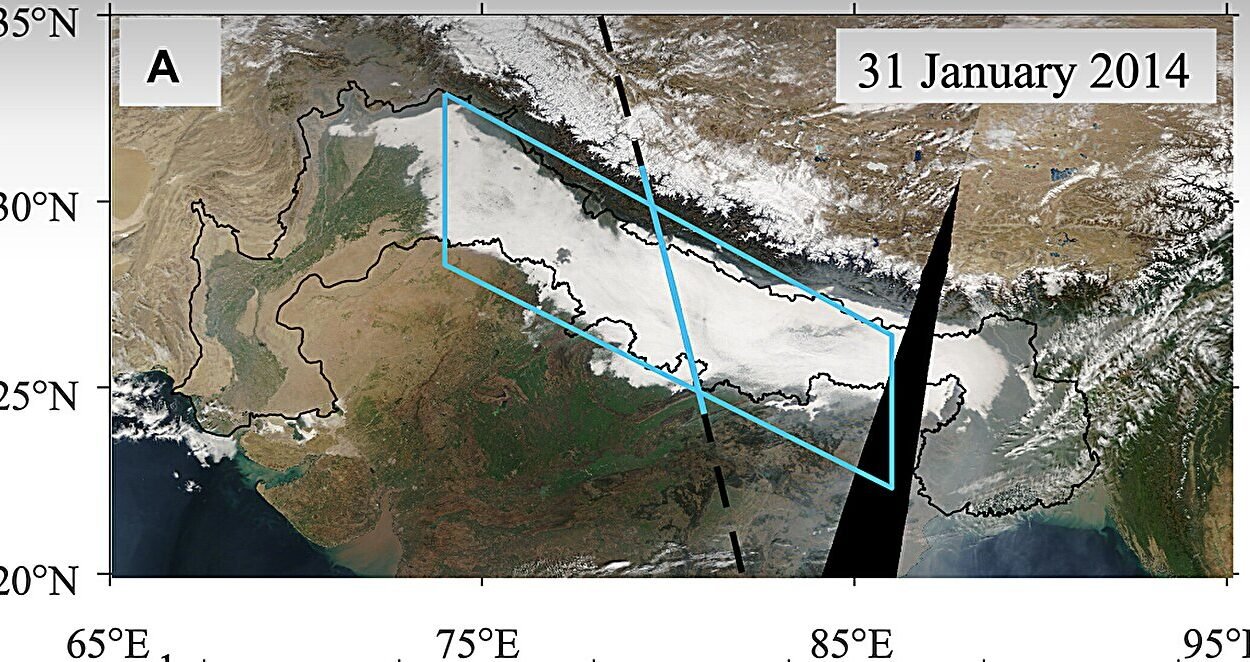

In 2021, sediment cores were drilled from the seabed off the Norwegian coast. At first glance, these long cylinders of mud might look unremarkable. But to Mei Nelissen, a Ph.D. candidate at NIOZ and Utrecht University, they were something extraordinary.

The cores were layered with astonishing clarity. Each thin band told a moment in time, some preserving changes season by season. Within these layers, Nelissen studied pollen and spores, tiny biological fingerprints that record what once grew on land nearby. Together, they formed a continuous narrative of how Earth’s ecosystems responded when the climate abruptly heated up during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, known as the PETM.

This was not a blurred snapshot of ancient disaster. It was a high-resolution movie.

The Forests That Vanished in Three Hundred Years

The pollen told a shocking story. At the studied site, forests dominated by coniferous trees collapsed astonishingly fast. Within a maximum of three hundred years after the explosive rise in atmospheric CO2, these trees disappeared from the record.

In their place, spores from ferns surged.

This shift mattered deeply. Ferns thrive in disturbed landscapes. Their sudden abundance signaled ecosystems under stress, landscapes recovering from damage rather than flourishing in stability. The transition revealed that terrestrial ecosystems did not slowly drift into a new balance. They were abruptly pushed out of one.

And the disruption did not fade quickly. For thousands of years, the pollen record showed ecosystems struggling to recover, locked in a prolonged state of upheaval.

Fire, Ash, and the Land Washing Away

Other clues lay mixed into the sediment. Tiny fragments of charcoal increased dramatically, clear evidence that forest fires became more frequent or intense as the climate warmed. Flames tore through vegetation that had once acted as a major carbon reservoir, releasing that stored carbon back into the atmosphere.

At the same time, the sediment told a story of destruction beyond fire. There was a rise in clay minerals, material that does not belong far offshore unless it has been carried there. This pointed to severe erosion, with entire sections of land breaking down and washing into the sea.

The warming did not just change what grew on land. It reshaped the land itself.

Seasons Frozen in Stone

What makes this discovery so powerful is not only what happened, but how clearly it can be seen. The sediment cores were exceptionally laminated, showing crisp, undisturbed layers that formed even on a seasonal scale.

Because of this, Nelissen and her colleagues could demonstrate something no one had shown so clearly before: trees and plants can respond to climate disruption with astonishing speed. Forests that took thousands of years to grow could unravel within a few human lifetimes.

The Earth did not hesitate. It reacted.

A Parallel Crisis in the Oceans

While Nelissen focused on land, the sea carried its own scars from the same event. In deep-sea drill cores studied elsewhere, researchers found a sudden absence of calcium carbonate.

The reason was simple and devastating. As the ocean absorbed enormous amounts of CO2, seawater rapidly acidified. Conditions became too hostile for many organisms to form calcium carbonate shells or skeletons. Life in the ocean, like life on land, was caught off guard by the speed of change.

The PETM was not a localized crisis. It was planetary.

A Warming Triggered by Unknown Forces

What caused this ancient upheaval remains uncertain. The PETM appears to have been driven by a combination of processes rather than a single trigger. Rising temperatures likely destabilized methane hydrates in the seabed, releasing methane into the atmosphere. At the same time, there was extensive volcanic activity, adding more greenhouse gases to the mix.

The Earth warmed further, faster, and fed back on itself.

Today, the cause of rapid warming is different. It is driven primarily by the burning of fossil fuels. But the pace of change invites comparison.

Faster Than the Deep Past

According to Nelissen, CO2 emissions today are about two to ten times faster than during the PETM. Yet the rate at which CO2 concentrations increased in the atmosphere back then is the closest geological parallel scientists have to what is happening now.

In geological terms, such a rate is described as unprecedented.

The sediment does not offer comfort. It offers warning.

When Disruption Feeds the Fire

One of the most sobering insights from this research is how disruption amplified warming rather than merely responding to it. Fires and erosion did not just follow climate change. They contributed to it.

As forests burned and soils eroded, additional carbon was released into the atmosphere. This extra carbon intensified global warming, creating a feedback loop that pushed the system further out of balance.

Nelissen emphasizes that terrestrial ecosystems are not passive victims. When destabilized, they can become active drivers of climate change themselves.

The Moment the Past Revealed Itself

The clarity of the sediment was so striking that its significance became apparent early on. During the 2021 expedition with the International Ocean Discovery Program, Nelissen’s supervisors, Joost Frieling and Henk Brinkhuis, noticed something special.

They found microfossils of the algae Apectodinium augustum, a key marker of the PETM. It was proof that these beautifully preserved layers belonged to the exact moment scientists are eager to understand. The discovery was so exciting that the team posed for a photo on deck.

That moment marked the beginning of Nelissen’s Ph.D. journey, rooted in mud, memory, and microscopic life.

Why This Ancient Story Matters Now

This research matters because it shows, with rare clarity, how fast Earth’s systems can unravel when pushed too hard. The PETM demonstrates that terrestrial ecosystems can respond quickly and dramatically to rapid climate change. Forests can vanish in centuries. Fires can surge. Landscapes can collapse and wash away.

We are already seeing signs that echo this past, including more forest fires. Researchers also expect more extreme weather, with intensified rainfall, flooding, and drought. The ancient sediment shows that these changes do not remain isolated. They interact, compound, and accelerate warming.

The PETM is not a prophecy. But it is a record of what happens when the carbon cycle is violently disrupted. Buried beneath the Norwegian Sea, the Earth left us a message written in pollen, charcoal, and clay.

It is a reminder that the planet remembers—and that its memory is telling us to take this moment seriously.

Study Details

Nelissen, Mei, Widespread terrestrial ecosystem disruption at the onset of the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2026). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2509231122. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2509231122