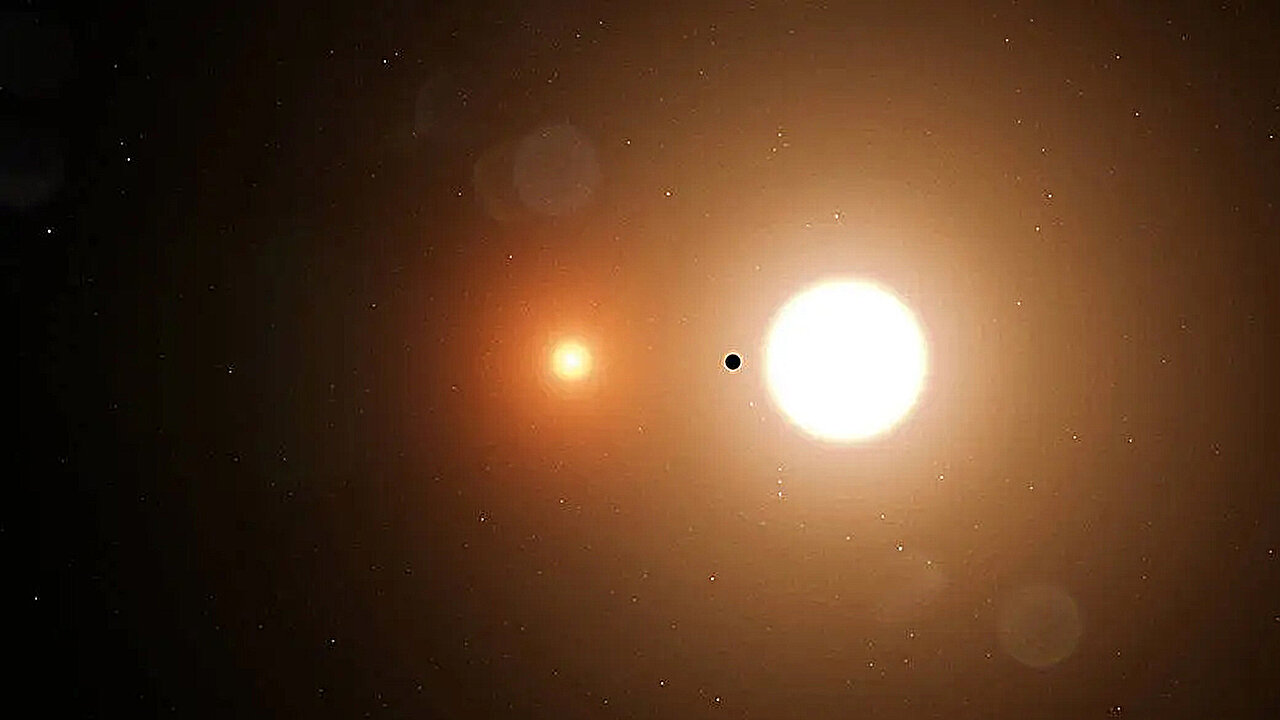

When astronomers look out into the galaxy, they see planets everywhere. Thousands upon thousands of exoplanets have been confirmed, most circling lone stars like our Sun. And yet, something feels off. Most stars are not solitary at all. They are born in pairs, locked in long gravitational dances with a companion. If planets are nearly universal and binary stars are equally common, then planets orbiting two suns should be everywhere.

But they are not.

Out of more than 6,000 confirmed exoplanets, only 14 are known to orbit both stars in a binary system. This scarcity is so extreme that it has baffled astronomers for years. Where are all the worlds with twin sunsets, the real-life versions of Tatooine?

Now, physicists at the University of California, Berkeley, and the American University of Beirut believe they have an answer. And at the heart of it lies a force so subtle yet so powerful that it reshapes spacetime itself.

The Hidden Hand of Einstein’s Gravity

The culprit, according to the researchers, is Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Normally invoked to explain black holes, warped spacetime, or the bending of light, relativity also quietly influences the motions of stars and planets in ways that are easy to overlook.

In most binary star systems, the two stars are similar in mass but not identical. They orbit each other in slightly stretched, elliptical orbits, rather than perfect circles. A planet that orbits both stars feels their combined gravitational pull, which causes its orbit to slowly twist, or precess, much like the wobble of a spinning top.

The binary stars themselves also precess. But here is the key twist in the story. Their precession is driven mainly by general relativity, not classical Newtonian gravity. Over time, the stars raise tides on each other that slowly shrink their orbit. As the stars draw closer, their relativistic precession speeds up.

The planet, meanwhile, experiences the opposite fate. As the binary tightens, its gravitational grip on the planet weakens, and the planet’s own precession slows down.

Eventually, these two motions fall into step.

When Orbits Fall Into a Dangerous Rhythm

There comes a moment when the precession of the planet’s orbit exactly matches that of the binary stars. This is not a peaceful alignment. It is a resonance, and it is catastrophic.

At resonance, the planet’s orbit begins to stretch dramatically. Its path becomes more and more elongated, carrying it far from the stars at one end, and then plunging it perilously close at the other. This closest approach, known as periastron, can spell doom.

“Two things can happen,” said Mohammad Farhat, a Miller Postdoctoral Fellow at UC Berkeley and the study’s lead author. Either the planet drifts too close to the binary and is torn apart or swallowed, or its orbit becomes so disturbed that it is flung entirely out of the system.

In both cases, the planet is gone.

This process does not take billions of years. Once resonance begins, destruction follows within tens of millions of years, a blink of an eye in the lifetime of a star. Over cosmic timescales, the result is a near-total clearing of close-in circumbinary planets.

The Transit Surveys That Found a Desert

The mystery became impossible to ignore with the rise of planet-hunting missions like NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope and the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). These missions search for planets by watching for tiny dips in starlight as a planet passes in front of its star.

Kepler also identified about 3,000 eclipsing binary stars, systems where the two stars periodically pass in front of one another. Based on what astronomers knew about single stars, they expected around 10% of these binaries to host detectable planets. That would mean hundreds of discoveries.

Instead, they found just 47 candidate planets, and only 14 have been confirmed.

Even more striking, none of these planets orbit tight binaries with orbital periods shorter than about seven days. These are precisely the systems where transits should be easiest to detect. Instead, they represent what Farhat calls “an absolute desert.”

The Edge Where Planets Barely Survive

Binary stars come with another hazard: an instability zone surrounding them. Inside this region, the gravitational tug-of-war between two stars and a planet becomes so chaotic that no orbit can remain stable. Any planet that wanders too close is either expelled or destroyed.

Curiously, 12 of the 14 known circumbinary planets orbit just outside this dangerous boundary. This suggests they did not form there but migrated inward from farther out in the system.

Trying to form a planet at the edge of the instability zone, Farhat explained, would be like “trying to stick snowflakes together in a hurricane.” The fact that planets sit right at this boundary hints at a violent past shaped by gravitational upheaval.

Relativity-driven resonance provides the missing link. As binary stars tighten and their relativistic precession accelerates, planets are pushed into ever more extreme orbits until they cross into the instability zone and vanish.

Models That Sweep Planets Away

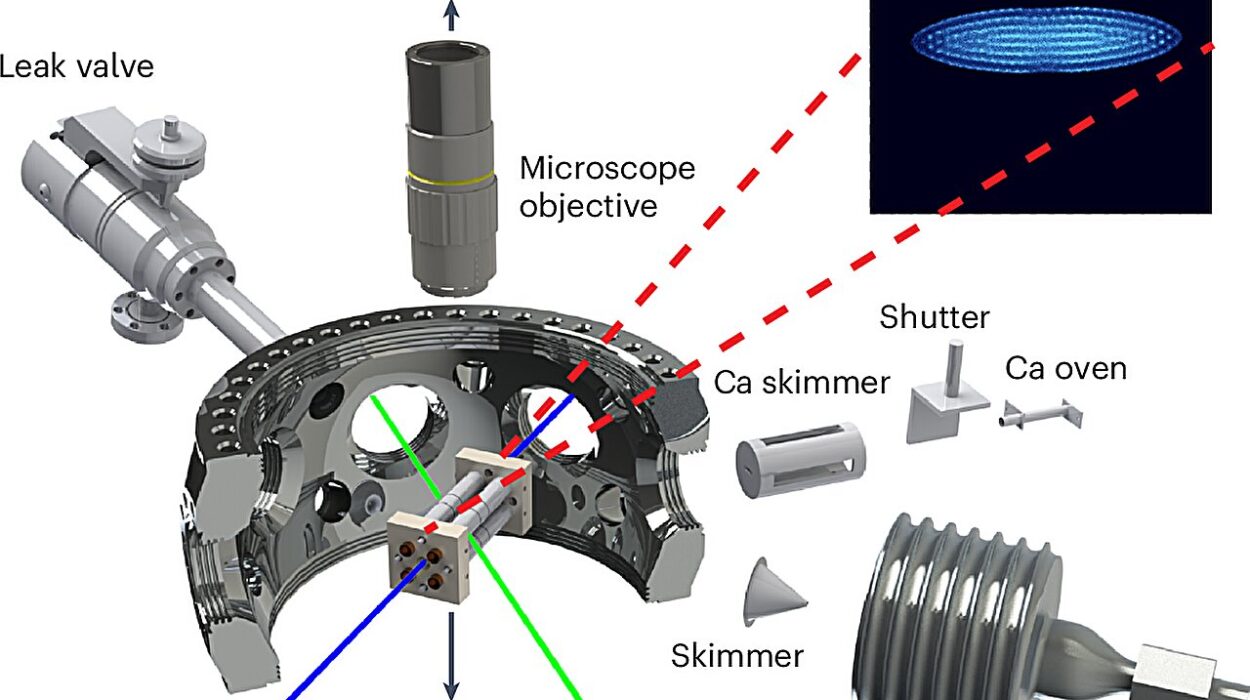

To test their idea, Farhat and Jihad Touma, a physics professor at the American University of Beirut, built detailed mathematical and computer models of circumbinary systems. The results were stark.

Their calculations show that general relativistic effects disrupt about eight out of every ten exoplanets orbiting tight binaries. Of those disrupted planets, 75% are destroyed, either by being swallowed or torn apart.

This mechanism alone is enough to explain why close-in circumbinary planets are so rare, without invoking additional chaos from passing stars or other external disturbances.

“Just the natural way you form these tight binaries,” Farhat said, “you get rid of the planet naturally.”

A Familiar Echo From Mercury’s Orbit

The physics at work here echoes a famous moment in scientific history. More than a century ago, astronomers noticed that Mercury’s orbit precessed slightly faster than Newton’s laws could explain. Einstein’s general theory of relativity provided the missing piece, becoming its first major triumph.

In Mercury’s case, relativity added a tiny correction that stabilized the planet’s motion. In binary star systems, the same effect becomes far more dramatic. As stars spiral closer together over billions of years, relativistic precession grows stronger, reshaping entire planetary systems.

A circumbinary planet caught in resonance sees its orbit stretched to extremes while staying locked in step with the shrinking stellar pair. On that path, it inevitably crosses the instability zone and is swept away.

Why the Missing Planets Matter

This research does more than solve a statistical puzzle. It shows that general relativity plays a decisive role even in systems once thought to be governed entirely by Newtonian gravity. The absence of planets around tight binaries is not a failure of planet formation or a limitation of telescopes. It is the natural outcome of spacetime itself bending the rules.

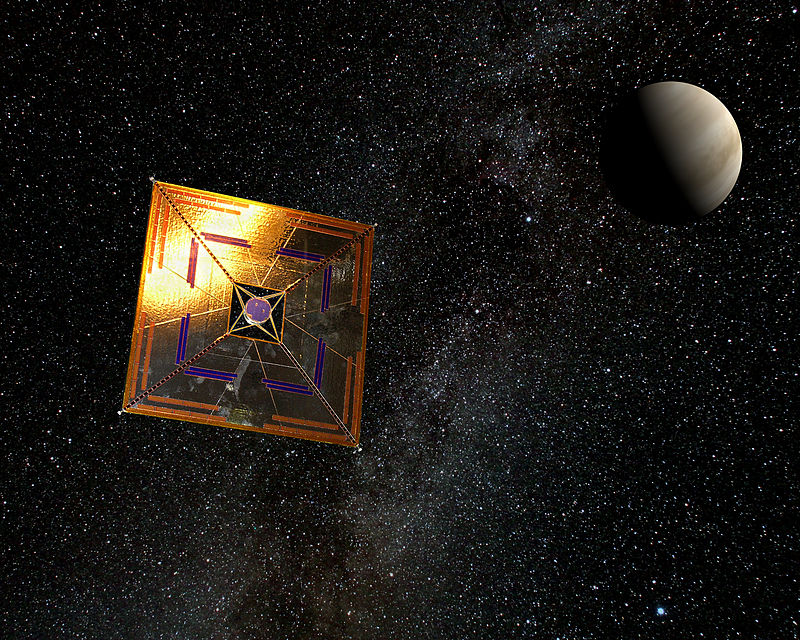

The findings also suggest that binary stars may host many planets that lie too far out to detect with current transit techniques. These worlds are not gone, just hidden beyond our reach.

More broadly, the work reveals how subtle physical effects can shape the architecture of planetary systems, quietly determining which worlds survive and which are erased. Nearly a century after Einstein rewrote gravity, his theory continues to explain not just how planets move, but why some never get the chance to exist at all.

In a universe filled with stars that come in pairs, it turns out that gravity itself decides how lonely those stars must remain.

Study Details

Mohammad Farhat et al, Capture into Apsidal Resonance and the Decimation of Planets around Inspiraling Binaries, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2025). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/ae21d8