For decades, a quiet gap sat in the story of lungfish evolution, like a missing chapter torn from a very old book. Scientists knew the opening lines and they knew the later pages, but the crucial middle was gone. Now, from the rocks of Zhaotong in Yunnan Province, that missing chapter has finally spoken.

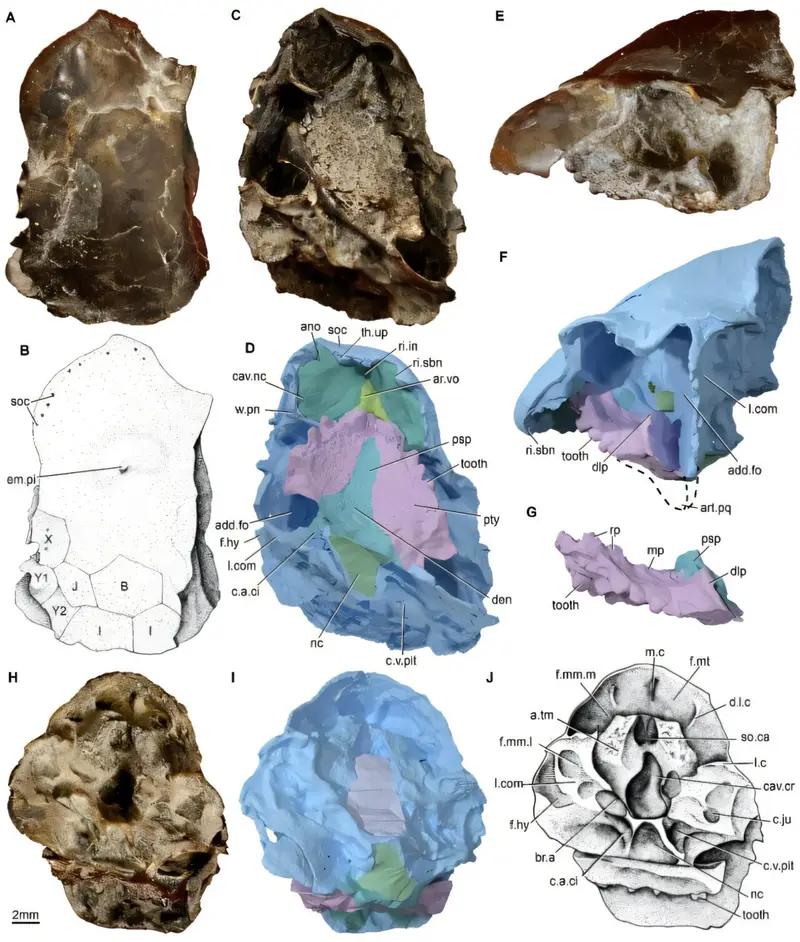

A research team led by Prof. Zhu Min of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has identified a new species of fossil lungfish preserved from the Early Devonian Period. The species, named Paleolophus yunnanensis, lived around 410 million years ago, and its discovery offers something paleontologists have searched for over many years: a clear anatomical bridge between the earliest confirmed lungfishes and their later relatives. The findings were published recently in the journal Current Biology, marking a significant moment in the study of vertebrate evolution.

What makes this discovery remarkable is not just its age, but its completeness. Encased in stone for hundreds of millions of years, a tiny skull measuring only 25 millimeters long has emerged as a powerful storyteller, revealing how lungfishes transformed during a critical moment in their history.

The Long Mystery of Lungfish Origins

Lungfishes occupy a special place in the tree of life. They are the closest living relatives of tetrapods, the group that eventually gave rise to animals with four limbs. Their lineage first appeared during the Devonian Period, a time when vertebrate life was experimenting boldly with new forms. Lungfishes diversified rapidly during this era, spreading into many ecological roles. Yet today, only three genera survive, distant echoes of a once-flourishing group.

Despite their importance, the early evolutionary steps of lungfishes have remained frustratingly obscure. Scientists had identified Diabolepis speratus as the earliest confirmed lungfish species, discovered in Early Devonian rocks in South China. They also knew much about later lungfishes that clearly displayed the defining features of the group. But the transition between these stages—the moment when primitive forms gave way to true lungfishes—had remained elusive.

This absence was not due to a lack of effort. Fossils from this interval are rare, often flattened or incomplete, leaving critical anatomical details hidden or destroyed. Without a well-preserved specimen, the evolutionary story could not be fully told. Paleolophus yunnanensis changes that.

A Small Skull With a Big Story to Tell

At first glance, the fossil might not seem extraordinary. Its skull is small enough to rest comfortably on a fingertip. But its preservation is unprecedented. Paleolophus represents the world’s first known three-dimensionally preserved lungfish skull from the Pragian Stage of the Early Devonian. Unlike flattened fossils that lose depth and spatial relationships, this skull retains its original three-dimensional structure, allowing scientists to examine it in extraordinary detail.

Using high-resolution CT scans, the research team was able to peer inside the fossil without damaging it. These scans revealed a mosaic of features that immediately caught the researchers’ attention. Paleolophus carries primitive traits seen in Diabolepis, including teeth on the upper lip and a prominent pineal region. At the same time, it shows characteristics typical of early true lungfishes, placing it squarely between the two evolutionary stages.

This combination is precisely what scientists had been searching for. Paleolophus does not simply resemble earlier or later forms; it connects them. Its anatomy captures evolution in motion, frozen at a moment when lungfishes were rapidly reshaping themselves.

A Face Built for Survival

Beyond its role as an evolutionary link, Paleolophus reveals hints about how it lived. The fossil skull shows an unusually enlarged nasal cavity, suggesting an enhanced sense of smell or specialized respiratory adaptations. Even more striking are its strongly developed jaw muscles, far more robust than those seen in earlier forms.

These features suggest that Paleolophus may have fed on hard-shelled prey, requiring both strength and precision to crush its meals. Such an adaptation hints at ecological experimentation, as lungfishes explored new feeding strategies during their early diversification.

One of the most important anatomical features lies deeper within the skull. The palatoquadrate–neurocranial region, part of the jaw and braincase structure, is partially fused. This detail might sound technical, but its significance is profound. Early sarcopterygians possessed a primitive “dual articulation” in this region, while true lungfishes have an autostylic skull configuration. Paleolophus preserves a transitional stage between these two conditions, offering direct evidence of how one structural system evolved into another.

This single feature alone captures a moment of evolutionary transformation that had previously existed only as a hypothesis.

Racing Through Evolutionary Time

By analyzing the CT data alongside phylogenetic studies, the research team placed Paleolophus at the base of Eudipnoi, a newly refined taxonomic group that includes all lungfishes except the earlier Diabolepis. This positioning clarifies the lungfish family tree and brings order to a previously tangled evolutionary picture.

Precise geological dating adds another layer of insight. The study indicates that the evolutionary transition from Diabolepis to true lungfishes occurred over a remarkably short period, between 416 and 412 million years ago. In evolutionary terms, four million years is a blink of an eye.

This compressed timeline highlights a burst of rapid diversification early in lungfish history. Rather than changing slowly and gradually, lungfishes appear to have undergone swift anatomical innovation, adapting quickly to their environments. Paleolophus stands as direct evidence of this accelerated evolutionary phase.

Clues Written Across Ancient Oceans

The implications of the discovery extend beyond anatomy and timelines. Paleolophus also offers clues about the geography of the ancient world. The research team noted morphological similarities between Paleolophus and Early Devonian lungfishes found in North America.

These similarities suggest that the South China Plate and the North American Plate were either connected or geographically close during the Early Devonian. In other words, ancient lungfishes may have moved across regions that are now separated by vast oceans. Their fossils preserve not only biological history, but the shifting architecture of Earth itself.

Such biogeographical insights help scientists reconstruct ancient continental arrangements and understand how early vertebrates dispersed across the planet.

Why This Discovery Matters

Paleolophus yunnanensis matters because it turns an abstract evolutionary gap into a tangible reality. It shows, with physical evidence, how one group of vertebrates transformed into another. It captures evolution not as a vague process, but as a sequence of anatomical steps preserved in bone.

This discovery deepens our understanding of lungfishes, the closest living relatives of tetrapods, and by extension, it informs our understanding of the broader evolutionary path that eventually led to life on land. By revealing how quickly and creatively early lungfishes diversified, it challenges assumptions about the pace of evolutionary change.

Perhaps most importantly, Paleolophus reminds us of the power of fossils to reshape scientific narratives. A skull just 25 millimeters long, locked in stone for 410 million years, has filled a gap that puzzled researchers for decades. It demonstrates that the history of life is not complete, but it is waiting—patiently, silently—for the right moment to be uncovered.

More information: Tuo Qiao et al, A new fossil fish sheds light on the rapid evolution of early lungfishes, Current Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.11.032