In the ancient seas that once blanketed the land we now know as Canada, a bizarre creature darted through the water with swimming flaps undulating like wings, three eyes scanning its surroundings, and jointed claws poised for ambush. This predator, Mosura fentoni, remained hidden in stone for over half a billion years—until now.

Paleontologists from the Manitoba Museum and the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) have unveiled this remarkable fossil from the world-renowned Burgess Shale, one of the richest fossil sites on Earth. Their findings, published in Royal Society Open Science, add a strange and captivating chapter to our understanding of Earth’s early ecosystems.

Mosura fentoni dates back 506 million years, to the Cambrian Period, a time when complex life was beginning to diversify rapidly in what scientists call the “Cambrian Explosion.” While this animal shares ancestry with other known radiodonts, its unique traits make it a rare evolutionary gem.

What is a Radiodont?

Radiodonts are an extinct group of marine animals distantly related to modern arthropods—an enormous family that includes insects, crabs, spiders, and millipedes. They’re often considered the early pioneers of predatory behavior in Earth’s oceans.

The most famous radiodont, Anomalocaris canadensis, grew up to a meter long and is often called the “T. rex of the Cambrian.” But Mosura, though only about the length of a human index finger, was no less impressive in its complexity and uniqueness.

A Sea-Moth with a Kaiju Name

With its flaps, claws, and abdomen-like tail, Mosura fentoni struck field collectors as reminiscent of a moth flitting beneath the waves. Its nickname—“sea-moth”—was more than poetic. It inspired the creature’s official scientific name, Mosura, a nod to “Mothra,” the iconic Japanese kaiju that often appeared as a winged protector in classic monster films.

Despite the lepidopteran inspiration, Mosura is not a distant cousin of modern moths. In fact, it hails from a much deeper branch of the evolutionary tree. It’s a cousin not just to insects, but to all arthropods—creatures that eventually crawled, swam, and flew their way across the planet.

A Unique Tail in the Radiodont Family

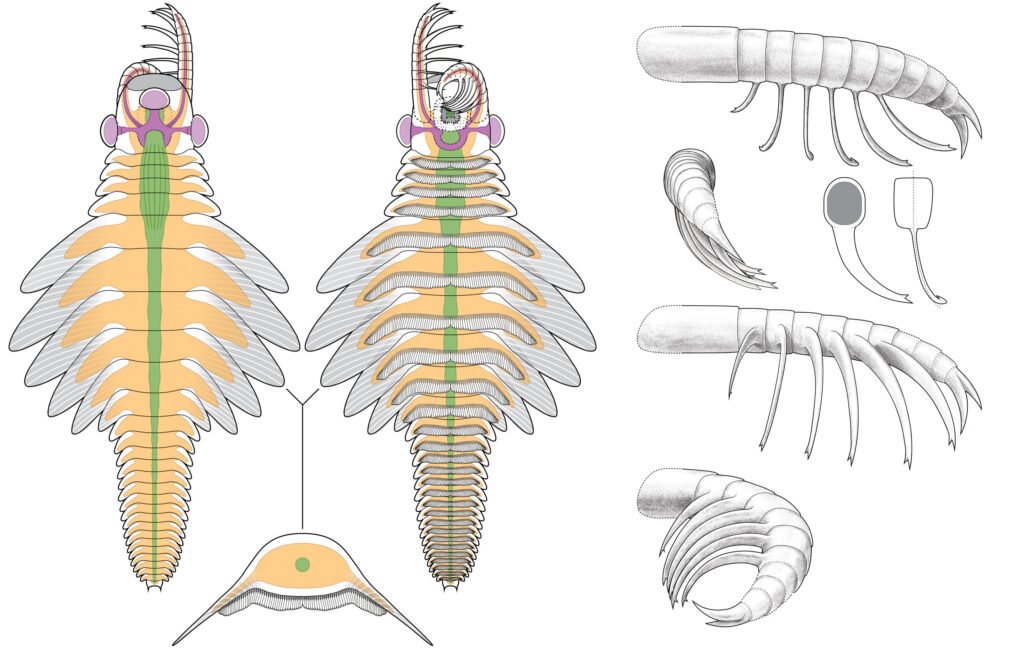

What sets Mosura fentoni apart from its radiodont kin is its posterior anatomy. At the rear of its body, researchers identified a distinctive feature never seen before in any other radiodont: a segmented, abdomen-like region lined with gill structures.

“Sixteen tightly packed segments form this abdominal structure, each bearing gills,” explains Joe Moysiuk, lead author of the study and Curator of Paleontology and Geology at the Manitoba Museum. “It’s an excellent example of evolutionary convergence—nature arriving at similar solutions in unrelated organisms.”

Indeed, this respiratory segmentation recalls features in modern horseshoe crabs, woodlice, and even insects. Why this adaptation appeared in Mosura remains unclear, but it likely hints at a specific habitat preference or lifestyle—perhaps more active swimming or greater oxygen demand in low-oxygen environments.

Built for Predation

Like its radiodont cousins, Mosura was built to hunt. Its anterior claws, or frontal appendages, were spiny and jointed—perfect tools for seizing small prey in Cambrian seas teeming with trilobites and early worms. Its circular mouth, lined with teeth and positioned on the underside of its head, likely spun and shredded food with gruesome efficiency.

With large swimming flaps positioned along its midsection, Mosura likely swam gracefully, possibly using a wave-like motion to maneuver through the water. Its narrowed abdominal region may have acted as a stabilizer, improving hydrodynamic efficiency.

Vision Through a Cambrian Lens

One of the most astounding revelations comes from the creature’s sensory system. Fossils of Mosura show preserved internal structures, including nerves leading from its three eyes.

“These nerve traces are incredibly rare,” says Jean-Bernard Caron, co-author and Curator of Invertebrate Paleontology at ROM. “They suggest a sophisticated visual system capable of processing images—similar to what we see in today’s arthropods.”

This discovery hints at a surprisingly advanced neurological capacity for such an early animal. Three eyes may have given Mosura a panoramic view of its environment, ideal for both hunting and evading predators.

The Ancient Heart of Mosura

Another striking feature revealed by the fossils is Mosura’s circulatory system. Unlike humans, who rely on closed circulatory systems with veins and arteries, Mosura had an open circulatory system. Its heart pumped blood into large internal cavities called lacunae, allowing it to bathe its internal organs directly.

These lacunae appear as reflective patches in the fossils, especially where they extended into the swimming flaps. Such details are rarely preserved, making Mosura one of the most informative windows into Cambrian physiology ever discovered.

“The preservation of these lacunae helps us decode similar structures in other fossils,” says Moysiuk. “It confirms that the open circulatory system was already in place in early arthropods, showing the deep evolutionary roots of this system.”

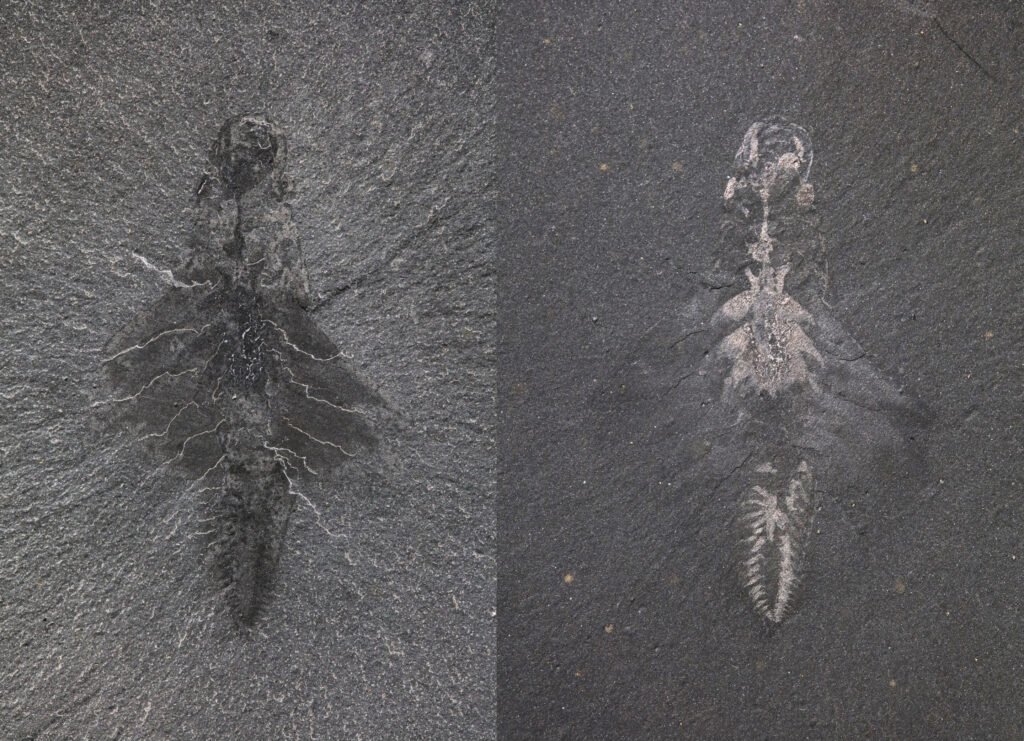

Hidden in Stone: A Fossil Record Spanning Decades

Of the 61 known Mosura specimens, nearly all were collected over a span of decades—from 1975 to 2022—primarily from the Raymond Quarry in Yoho National Park and, more recently, from Marble Canyon in Kootenay National Park.

Some specimens date back to work by Charles Walcott, the famed paleontologist who first discovered the Burgess Shale in the early 20th century. These long-archived fossils, kept in museum drawers for decades, finally received detailed analysis, yielding astonishing anatomical revelations.

“Museum collections, old and new, are a bottomless treasure trove,” says Moysiuk. “You just need to open a drawer, and the past comes alive.”

The Burgess Shale: Earth’s Time Capsule

Located in the Canadian Rockies, the Burgess Shale is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the world’s most significant fossil beds. Its fine-grained sediments preserved soft-bodied organisms in extraordinary detail, offering a unique glimpse into Cambrian ecosystems.

Parks Canada manages these fossil sites and has worked closely with scientists to protect them while sharing their significance with the public. The guided hikes to Burgess Shale sites are considered among the most awe-inspiring paleontological experiences in the world.

Sharing Mosura With the World

Soon, visitors will be able to marvel at Mosura in person. A specimen will go on display for the first time at the Manitoba Museum in Winnipeg. Meanwhile, other radiodont fossils—Anomalocaris, Stanleycaris, Cambroraster, and Titanokorys—are already showcased in ROM’s “Willner Madge Gallery: Dawn of Life” in Toronto.

These exhibits offer more than visual spectacle—they are journeys into deep time. They invite us to ponder life’s origins, the incredible diversity of forms it has taken, and the shared ancestry of everything that crawls, swims, or flies today.

Why Mosura fentoni Matters

Beyond its peculiar anatomy, Mosura fentoni represents a key evolutionary moment. It shows how early arthropods were already experimenting with body plans, respiratory systems, sensory processing, and circulatory mechanisms. In many ways, these experiments laid the foundation for the staggering diversity of life that would follow.

As paleontologists continue to uncover the secrets of Mosura and its ancient relatives, each fossil becomes a thread in a vast, unfinished tapestry—one that tells the story of how life rose from the ocean floor and began to shape the world we know.

In the silence of stone, a sea-moth whispers of a world long vanished. Thanks to science, we’re finally learning to listen.

Reference: Early evolvability in arthropod tagmosis exemplified by a new radiodont from the Burgess Shale, Royal Society Open Science (2025). DOI: 10.1098/rsos.242122