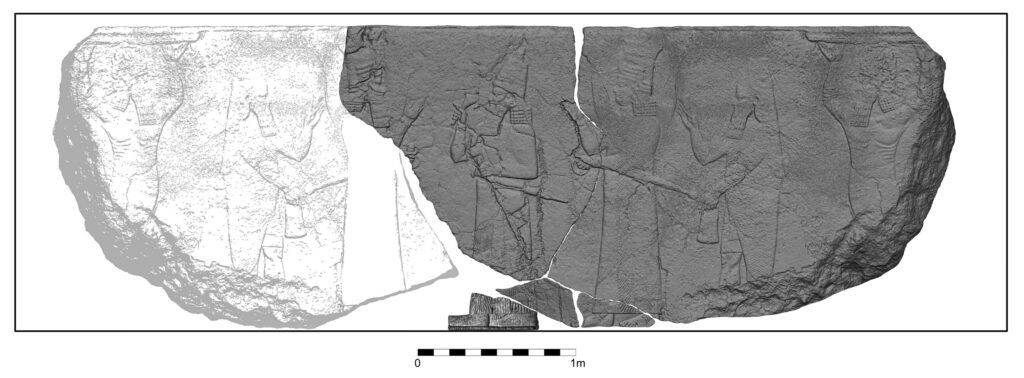

In the ancient sands of Iraq, beneath layers of history and time, archaeologists from Heidelberg University have brought to light a discovery of immense significance: a monumental relief hidden for over two millennia within the throne room of King Ashurbanipal’s North Palace in Nineveh. Measuring an astonishing 5.5 meters long, 3 meters high, and weighing about 12 tons, this relief is not just a marvel of size—it is a profound glimpse into the divine and political psyche of the mighty Assyrian Empire in the 7th century BC.

This isn’t merely an artifact—it’s a time capsule, a ceremonial canvas that once stood across from the grand entrance of the king’s throne room. Forgotten in a subterranean pit during the Hellenistic period, it has now emerged into the light of modern scholarship, bringing with it secrets, symbolism, and sacred stories etched in stone.

Nineveh: The Jewel of Assyria

Once the capital of the Assyrian Empire, Nineveh was a city of majesty and might. Located near today’s Mosul in northern Iraq, Nineveh reached its zenith under King Sennacherib in the late 8th century BC and later flourished under his grandson, Ashurbanipal. The North Palace, perched atop the Kuyunjik mound, was the empire’s beating heart—a place where power, religion, and royal grandeur converged.

While British explorers first unearthed many of the palace’s reliefs in the 19th century—now housed in the British Museum—this new discovery redefines the landscape of Assyrian art. It was found in a niche believed to be the throne room’s focal point, a sacred space designed to awe visitors with a visual declaration of divine rule.

A Divine Court in Stone

What sets this find apart is not only its magnitude but its unprecedented subject matter. In the center of the relief stands King Ashurbanipal himself—regal, poised, and commanding—flanked by two of the highest Assyrian deities: Ashur, the supreme god of the empire, and Ishtar, the fierce warrior goddess and patron deity of Nineveh.

These celestial companions were not mere decorative motifs. Their presence transforms the relief into a theological proclamation: the king’s authority was divinely sanctioned. By portraying Ashurbanipal among gods, the relief doesn’t just show a ruler—it depicts a man who stood shoulder to shoulder with divinity.

Behind these deities trail enigmatic figures—a fish-cloaked genius who bestows salvation and longevity, and a striking figure believed to represent a scorpion-man, a mythological guardian of sacred realms. Together, these elements suggest that a large winged sun disk once crowned the relief, a potent symbol of divine presence and cosmic harmony.

Hidden in Plain Sight

Why was such a magnificent piece hidden for so long?

According to Prof. Dr. Aaron Schmitt, director of excavations at the site, the relief was discovered in an earth-filled pit behind the niche it once adorned. This pit, believed to have been dug during the Hellenistic period (3rd–2nd century BC), shielded the fragments from looters and the British excavators of the 19th century.

This accidental preservation has now become a stroke of archaeological fortune. Unlike many ancient sculptures ravaged by time or conquest, this relief survived beneath the earth relatively intact, a buried treasure awaiting rediscovery.

Rediscovering a Lost Legacy

The discovery is part of the Heidelberg Nineveh Project, launched in 2018 under the direction of Prof. Dr. Stefan Maul. Since 2022, the team has focused on the Kuyunjik mound, meticulously unearthing and documenting the remains of Ashurbanipal’s North Palace.

According to Prof. Schmitt, the upcoming months will be dedicated to detailed analysis of the relief, both in terms of iconography and context. Using high-resolution imaging, 3D modeling, and contextual archaeological methods, the team hopes to publish a comprehensive report shedding light on this exceptional artifact.

Equally exciting is the plan—developed in collaboration with the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH)—to return the relief to its original location inside the throne room. Once restored and reassembled, this ancient masterpiece will be unveiled to the public, offering an immersive window into the splendor of the Assyrian court.

Ashurbanipal: The Last Great King

Ashurbanipal, who ruled from approximately 669 to 631 BC, was the last illustrious monarch of Assyria. Known for his military prowess and cultural achievements, he is perhaps most famous for his vast royal library—considered the first systematically organized library in history.

The newly discovered relief underscores not only his might but also his spiritual legitimacy. To be flanked by Ashur and Ishtar in a throne room is no casual honor; it is a bold claim to sacred kingship and eternal favor.

In an era when divine right was the bedrock of political rule, such imagery was not simply decorative—it was declarative. It proclaimed to all who entered the palace that Ashurbanipal was chosen, protected, and empowered by the gods themselves.

Art, Theology, and Power Intertwined

What makes this relief so unique among Assyrian artworks is the divine ensemble it depicts. According to Prof. Schmitt, “Among the many relief images of Assyrian palaces we know of, there are no depictions of major deities.” This changes the narrative.

Most palace reliefs showcased royal hunts, military victories, and scenes of tribute. Here, we see a different message—a deliberate interweaving of theology and kingship, a divine drama played out in stone. It is a striking departure from more secular themes, possibly intended for a select audience of high priests, foreign dignitaries, and royal advisors.

The inclusion of the fish-genius and scorpion-man further blurs the line between myth and reality, suggesting a cosmological structure where gods, spirits, and mortals coexisted, each playing a role in maintaining the order of the universe.

From Dust to Display

Resurrecting the relief from its centuries-long slumber is no small feat. Each fragment must be carefully analyzed, cleaned, conserved, and pieced together like a three-dimensional puzzle. Using advanced digital tools, researchers can simulate reconstructions, test hypotheses about the composition, and visualize how the entire relief may have appeared in its original grandeur.

The ultimate goal is more than academic. It is cultural revitalization. By placing the relief back into its ancient home, Iraqi heritage authorities and the Heidelberg team hope to transform Nineveh into a beacon of historical education, tourism, and pride.

Looking Ahead: A New Chapter for Nineveh

This discovery does more than enrich our understanding of Assyrian art—it reawakens Nineveh’s legacy. Once a thriving metropolis and cultural epicenter, the city suffered under centuries of neglect, looting, and more recently, devastating conflict.

Now, as peace slowly returns to northern Iraq, archaeology is playing a crucial role in healing and rebuilding. By unearthing and preserving these treasures, scholars are not just reconstructing history—they are reanimating a lost civilization.

With this monumental relief, Nineveh once again has a story to tell. A story of power, piety, and artistic brilliance. A story written in stone, hidden in earth, and now told to the world.

Conclusion: When Stones Speak

In a world driven by modern speed and fleeting digital memories, the discovery in Nineveh is a powerful reminder of the endurance of the human spirit. Long after empires fall and kings vanish, their stories remain etched in rock, waiting to be heard again.

Thanks to the careful work of Heidelberg University’s archaeologists, we can now listen. And what we hear is a voice from the ancient past—a king, a people, and a pantheon, speaking once more from the heart of Mesopotamia.