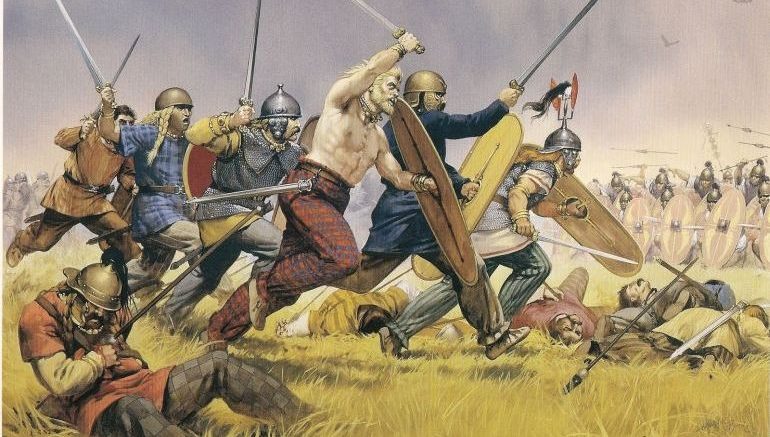

The Viking Age has long been portrayed through the lens of conquest, exploration, and maritime prowess—bearded warriors in longships, raids on distant shores, and seafaring myths immortalized in sagas. But a groundbreaking interdisciplinary study from the Universities of Leicester and Nottingham invites us to peer into a lesser-known, deeply human side of this world: pregnancy and childbirth. Titled “Womb Politics: The Pregnant Body and Archaeologies of Absent”, this research opens a new chapter in Viking studies by exploring the complex, often invisible stories of pregnancy, maternal risk, and unborn life in a society defined by its stark dualities.

Led by Dr. Marianne Hem Eriksen, Associate Professor of Archaeology at the University of Leicester, and Dr. Katherine Marie Olley, Assistant Professor in Viking Studies and Director of the Centre for the Study of the Viking Age at the University of Nottingham, the study dives into the narratives, art, and archaeological remnants of the Viking world. What they uncover is startling, raw, and poignant—a tapestry where pregnant women sometimes don martial helmets and fetuses are inscribed into the political plots of feuding families before they even draw breath.

Old Words, New Interpretations

At the heart of the research lies language—words as vessels of memory and belief. Dr. Olley’s work scours Old Norse sources for traces of how pregnancy was conceptualized in a world largely dominated by masculine myths and warrior ethos. Although the surviving texts postdate the Viking Age, they contain echoes of earlier thought. Language becomes a portal: in words like bellyfull, unlight, and the poetic phrase to walk not a woman alone, we glimpse how people might have viewed the pregnant body—as both individual and dual, fragile and fierce, sacred and social.

These evocative terms offer more than quaint linguistic relics. They suggest a worldview where pregnancy was far from a passive, hidden condition. Instead, it was woven into ideas of identity, vulnerability, and even power. In one saga, a fetus is destined to avenge his father’s murder, making his unborn presence a critical player in a blood feud. In another, the late-pregnant Freydís, unable to flee an attack, confronts her enemies with shocking defiance—exposing her breast and striking her chest with a sword to drive them away. These are not tales of retreat but of confrontation, where the maternal body becomes a site of resistance.

Martial Mothers and Iconic Imagery

Perhaps the most striking piece of evidence is a small silver figurine, long studied but only now interpreted through the lens of pregnancy. The figurine features a visibly pregnant woman, arms cradling her rounded belly, wearing what appears to be a helmet complete with a noseguard—a traditional emblem of Norse warriors.

While researchers are cautious not to draw simplistic conclusions—this isn’t proof of pregnant Viking shieldmaidens charging into battle—it is an unmistakable symbol. This figurine, contextualized by myth and language, suggests that the Norse imagination allowed for pregnant women to be not only maternal but also martial. They could be life-bringers and threat-wielders, sacred and feared, creators and avengers.

“This is not a pacified pregnant body,” explains Dr. Olley. “This is a body that holds presence, weight, and perhaps authority in ways we’re only beginning to understand.”

Archaeologies of Absence: Where Are the Mothers?

Despite the strong narrative and artistic presence of pregnancy, physical evidence remains elusive. The researchers point out a disturbing absence in the archaeological record. Across thousands of Viking Age burials, there are only a handful of possible mother-infant graves. This is puzzling, especially given the well-documented dangers of childbirth in pre-modern societies.

So where are the rest?

Some infants appear buried in domestic spaces, such as beneath floors of homes—a practice seen in other ancient cultures as well. Others are simply missing. Whether this is due to the decomposition of tiny bones, cultural burial practices, or a deeper social reality—such as the lower social value assigned to infants or enslaved people—the answer remains uncertain. But the absence is itself a powerful presence, raising questions about how societies value life, both before and after birth.

The Politics of the Womb

One of the study’s central insights is that pregnancy is not just a biological fact—it’s a political one. “It verges on the banal to say it,” remarks Dr. Eriksen, “but pregnancy is an absolute necessity for all forms of reproduction—demographic, social, economic, political.” Yet, even something so foundational can become the subject of marginalization, exploitation, or control.

Legal texts from the Norse world reveal stark realities. Pregnancy in an enslaved woman could be considered a “defect,” affecting her sale value. Children born to enslaved or subordinate individuals were treated as the property of the owner, stripped of kinship, identity, and autonomy. These grim details are reminders that not all wombs were equal under Viking law. Some were cherished, others commodified. Some led to family, others to further subjugation.

Reframing the Viking Age

The implications of this research stretch far beyond Viking studies. It challenges how history—and archaeology—frames gender, body, and power. Conventional portrayals of the Viking Age have long emphasized male warriors, territorial conquests, and seafaring sagas. The study of pregnancy demands a new kind of lens—one that sees not just axes and armor but also wombs and cradles; not just longships but long labors.

Pregnancy has historically been seen as a “private” matter, a natural process confined to the domestic sphere. But this research flips that assumption. In the Viking world, the pregnant body appears in legal codes, mythic sagas, and even warlike figurines. It becomes something visible, active, and socially entangled. It touches on personhood, law, kinship, honor, and even vengeance.

This reframing doesn’t just give women and mothers a place in Viking history—it reconfigures the whole narrative structure.

A Modern Echo

There’s a haunting resonance between the findings of this study and the contemporary world. Today, debates about reproductive rights, maternal healthcare, and bodily autonomy remain deeply political and polarizing. Questions about when personhood begins, who controls the pregnant body, and how societies value unborn or newborn lives are as urgent now as they were in the ninth century.

The Viking Age may be a thousand years gone, but its stories—like Freydís brandishing a sword with a swollen belly—still speak. They speak of fear and power, of silence and presence, of the womb as both a cradle and a battlefield.

Conclusion: Beyond Myth and Memory

The interdisciplinary work of Dr. Eriksen and Dr. Olley is more than just an academic breakthrough. It is an act of excavation—not just of artifacts but of lives long neglected by traditional history. By examining the words, art, and burial practices of the Viking Age, they reveal a society that both revered and feared the pregnant body.

In doing so, they don’t just give us new Viking stories. They give us a richer, fuller, and more honest view of the past. One where power comes not only from the sword but from the womb. One where life is as revered—and as dangerous—as war. And one where, even in silence, the pregnant body refuses to be absent.

Reference: Marianne Hem Eriksen et al, Womb Politics: The Pregnant Body and Archaeologies of Absence, Cambridge Archaeological Journal (2025). DOI: 10.1017/S0959774325000125