In a quiet corner of North Yorkshire, beneath fields that today ripple with grain, lay the glittering remains of an international economy nearly twelve centuries old. The Bedale hoard, a remarkable Viking-Age treasure discovered in 2012, has long been admired for its craftsmanship and scale. But new research led by Dr. Jane Kershaw, Associate Professor of Viking Age Archaeology at the University of Oxford’s School of Archaeology, has revealed that its story is far richer—and far more global—than the old tales of Viking raiders might suggest.

For generations, the popular image of Vikings has been one of ruthless warriors storming the coasts of Britain, plundering monasteries, and vanishing back to their longships with stolen gold and silver. Yet, as Dr. Kershaw’s team has shown, the Vikings were also savvy merchants operating within vast trade networks that reached deep into the Islamic world.

From Raids to Trade Routes

The Bedale hoard, dating to the late ninth or early tenth century, contains 29 silver ingots alongside elaborate neck-rings and other jewellery. While much of its silver originated from Western Europe—likely Anglo-Saxon and Carolingian coins obtained through raids, ransom, or tribute—geochemical testing has revealed an unexpected surprise: nearly a third of the hoard’s silver came from thousands of miles away, minted as Islamic dirhams in the heart of the Abbasid Caliphate.

These coins, once traded across bustling markets in places corresponding to modern-day Iran and Iraq, travelled north along the fabled Austrvegr, the “eastern way” that linked Scandinavia with the Silk Road. From there, they made their way westward with Viking merchants and settlers into England. This finding paints a picture of Vikings not just as predators, but as active participants in a complex web of Eurasian commerce.

Science Unlocks the Silver’s Secrets

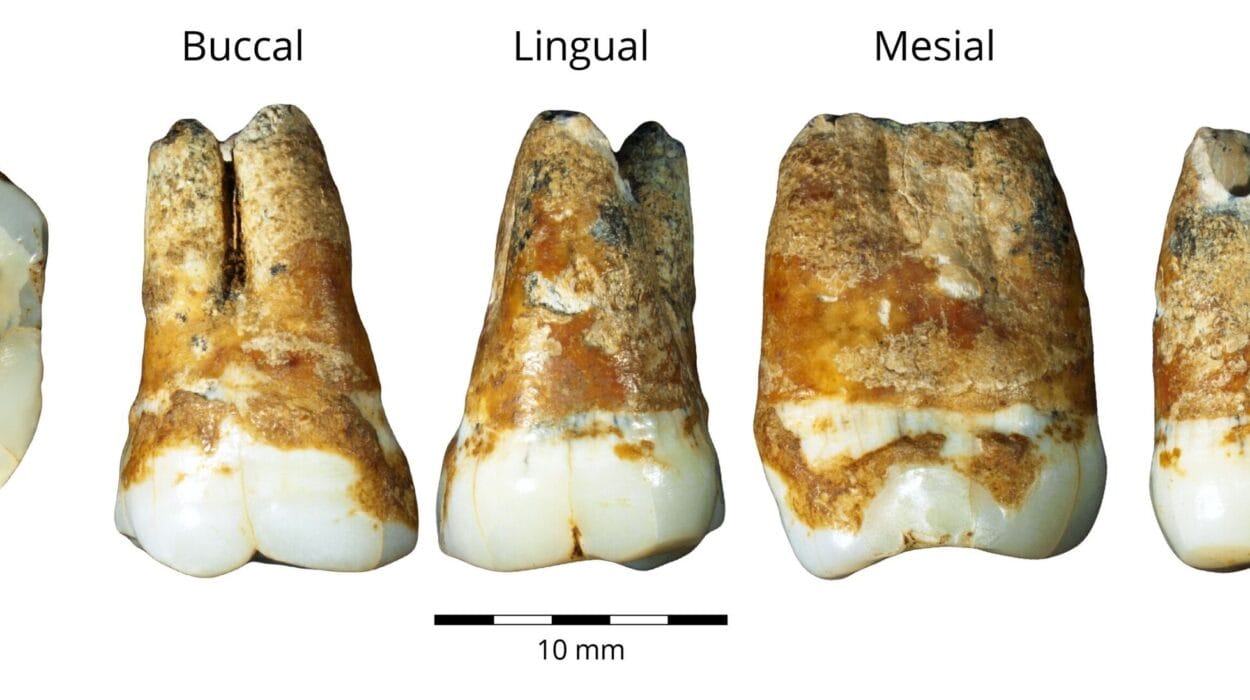

The team used a combination of lead isotope analysis and trace element profiling—methods that can pinpoint the geological origin of metal ores—to identify the silver’s sources. By comparing isotopic “fingerprints” of the Bedale ingots and jewellery with known samples from historical mining and minting sites, they distinguished three principal origins: Western European coinage, Islamic dirhams, and mixed-source silver combining both.

Nine ingots, almost one-third of the hoard, matched the isotopic profile of Abbasid Caliphate silver. These were likely melted down from dirhams and recast into bars, fitting into the Viking bullion economy where silver circulated by weight rather than by coin.

Bedale’s Place in a Global Economy

For Dr. Kershaw, the research transforms our understanding of Viking life in England.

“Most of us tend to think of the Vikings primarily as raiders,” she explained. “What the analysis of the Bedale hoard shows is that that is only part of the picture. They also made great profits from long-distance trade routes connecting northern Europe to the Islamic Caliphate. We can now see that they brought large quantities of this Islamic silver with them when they established settlements in England.”

Bedale today may be a quintessential English market town, but in the Viking Age it sat within a thriving network of exchange that stretched from Yorkshire’s fields to the markets of Samarkand and Baghdad.

Craftsmanship and Cultural Fusion

The study also uncovered evidence of local metalworking sophistication. Some silver objects in the hoard were refined with lead sourced from the North Pennines—indicating that Viking smiths in both Scandinavia and England were reprocessing and blending silver to create new forms. One spectacular neck-ring, formed from multiple twisted rods, appears to have been cast using a mix of eastern and western silver, possibly crafted in northern England. Such pieces not only demonstrate technical skill but also symbolize the merging of cultures and economies.

A Broader Economic Strategy

The Bedale hoard adds weight to the growing body of scholarship suggesting that Viking wealth acquisition was far more complex than simple looting. Military campaigns, yes—but also tribute collection, commercial exchange, and the melting and recasting of imported silver into portable, standardized forms. In this way, the Vikings sustained an interconnected bullion economy that linked disparate corners of Europe, the Middle East, and Central Asia.

Science Brings the Past Into Focus

Beyond its historical value, this research highlights the power of modern scientific techniques to reveal hidden stories in ancient artifacts. By reading the atomic “signatures” within the Bedale silver, archaeologists can now place Yorkshire within the vast economic map of the Viking world—a map that includes not only the monasteries of Lindisfarne but also the desert caravanserais of the Islamic Caliphate.

The findings, published in Archaeometry, invite us to reconsider the Viking legacy. They were not just marauders who vanished into legend; they were also entrepreneurs, craftsmen, and traders whose reach spanned continents. And in the soil of Bedale, their global connections still glint beneath the English sun.

More information: Jane Kershaw et al, The Provenance of Silver in the Viking-Age Hoard From Bedale, North Yorkshire, Archaeometry (2025). DOI: 10.1111/arcm.70031