It begins, like so many timeless mysteries, with a story—a tale passed down across millennia, told and retold until myth and memory blur. The first whispers of Atlantis did not come from crumbling ruins or ancient scrolls, but from the mind of one man: Plato. Writing around 360 BCE, the Greek philosopher painted a vivid picture of a powerful island civilization that vanished in a single day and night, swallowed by the sea in a cataclysm no one could stop.

This was not simply a parable. To Plato, Atlantis was a warning—a paragon of greatness undone by moral decay. Yet to later generations, it became something more: a riddle etched into the bedrock of our imagination. What kind of place was Atlantis? Did it ever exist? If so, what fate could wipe out an entire civilization, leaving behind not even a whisper of stone?

As we explore the story of Atlantis and what may have truly happened to its people, we step into a liminal space—where myth dances with geology, where archaeology peers into ancient memories, and where the desire to know our forgotten past burns as brightly as ever.

Plato’s Atlantis: Philosophy or History?

Plato’s dialogues Timaeus and Critias are our only primary sources for the Atlantis story. According to him, Atlantis was a powerful maritime empire located “beyond the Pillars of Heracles”—the ancient name for the strait of Gibraltar. It was said to be larger than Libya and Asia combined, with lush forests, mineral wealth, and advanced engineering. Its kings descended from the god Poseidon and ruled with justice and wisdom—at least, for a time.

But then, pride and greed infected them. The Atlanteans waged war against Athens and the known world. As divine punishment, the gods sent earthquakes and floods, submerging Atlantis into the ocean.

Modern scholars have debated for centuries whether Plato’s account was allegory or factual history. Some argue it was a moral fable, using a fictional Atlantis to critique Athenian society. Others believe Plato may have preserved a distorted echo of a real prehistoric civilization—one lost not to legend, but to time.

The Allure of a Lost Civilization

There is something universally haunting about the idea of a vanished world. Atlantis is not merely a city beneath the sea—it is a symbol of potential and downfall, of hubris punished by nature. That duality gives the story a kind of immortality.

Over the centuries, the Atlantis myth has taken on a chameleon-like quality. Enlightenment thinkers searched for it as a lost utopia of knowledge and rational order. Victorian explorers linked it to the Biblical flood or ancient Egypt. In the 20th century, it became a favorite subject for mystics, occultists, and pseudoscientific theorists.

But beneath the noise of speculation, a more grounded question remains: could Atlantis have been real, or at least based on something real? And if so, what happened to its people?

To answer this, we must look not to fairy tales, but to the earth itself.

Earthquakes, Volcanoes, and the Power of the Sea

Long before satellites and seismic data, humans lived close to nature’s pulse—and paid the price when it turned violent. Entire civilizations have vanished from the historical record due to disasters so massive they seem almost mythical in retrospect.

One of the most compelling real-world candidates for Atlantis is the island of Thera—modern-day Santorini in the Aegean Sea. Around 1600 BCE, Thera was home to a flourishing Minoan civilization, one of the earliest advanced cultures in Europe. They had multi-story buildings, intricate plumbing, colorful frescoes, and a thriving trade network.

Then came the eruption.

The Thera volcano exploded with a force many times greater than Krakatoa. Ash darkened the sky across the Mediterranean. Tsunamis swept over coastlines. The center of the island collapsed into the sea, forming the caldera we see today.

The Minoan outposts on Thera were obliterated. The main Minoan centers on Crete survived initially, but their society began to decline soon after. Some scientists and historians propose that this eruption, combined with earthquakes and later invasions, triggered the downfall of the Minoan civilization—and that the memory of this cataclysmic event evolved, over generations, into the Atlantis myth Plato eventually wrote down.

Could the people of Atlantis, then, have been the people of Thera? Not swallowed by divine wrath, but by one of the greatest natural disasters in recorded prehistory?

Memory Across Millennia

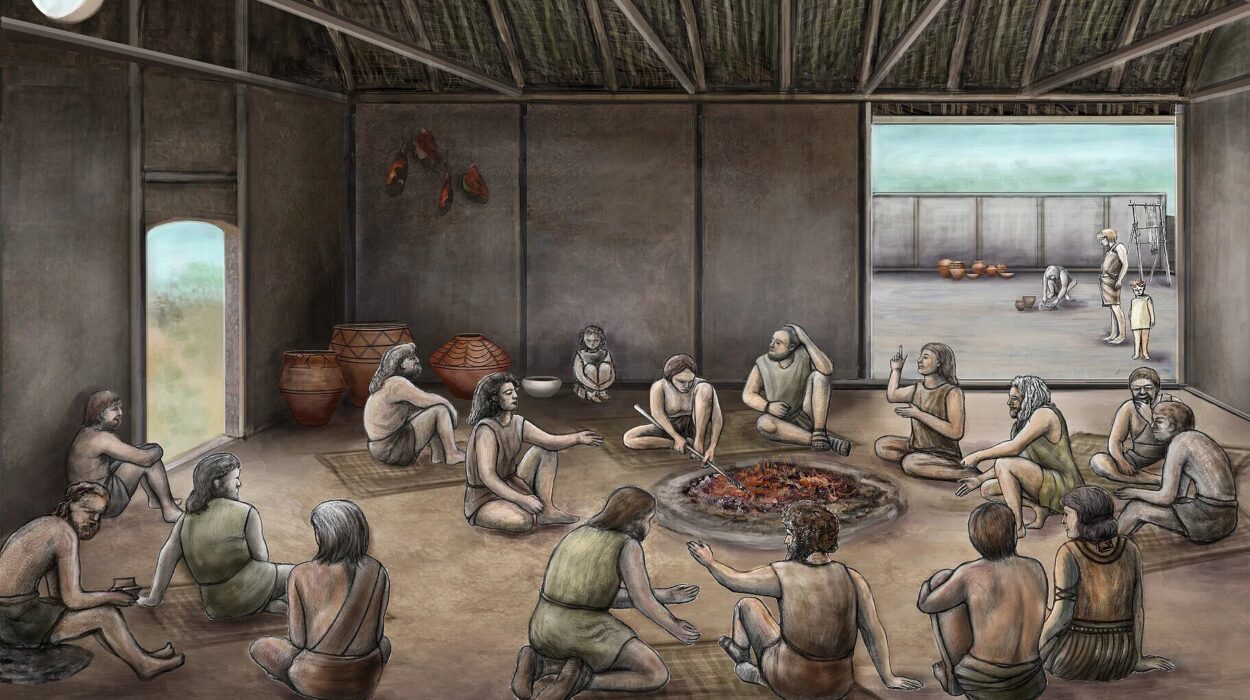

To understand how a real event can become a legend, we must appreciate the nature of oral tradition. Ancient societies preserved knowledge not through written records, but through storytelling. A cataclysm like Thera’s eruption would not be forgotten. It would echo through generations in the form of tales—tales of fire from the sky, waves that swallowed cities, and lands that vanished beneath the sea.

By the time these stories reached Plato—more than a thousand years later—they may have morphed in scale and detail. Names changed. Geography blurred. The gods replaced tectonic forces. Yet the core remained: a great civilization lost in a single, terrifying moment.

This process is not unique to Atlantis. Similar flood myths exist around the world—from the Epic of Gilgamesh to the Biblical Noah, to Aboriginal and Native American traditions. Perhaps these are not separate stories, but different cultural memories of shared trauma—floods, tsunamis, and rising seas that erased whole worlds.

If Atlantis is one of these memories, it may be less about a single lost city and more about a pattern that has repeated throughout human history.

Other Candidates, Other Mysteries

Thera may be the strongest scientific match for Atlantis, but it’s not the only possibility. Across the globe, ruins and geological oddities have invited speculation.

Some point to the submerged ruins off the coast of Bimini in the Bahamas—the so-called “Bimini Road”—as evidence of an Atlantean structure. Others have explored the idea that Atlantis lay in the Caribbean, Antarctica, or even under the Sahara Desert, where an oval-shaped geological formation called the Richat Structure resembles Plato’s description of concentric rings.

Each theory attempts to pin the myth to a map. But perhaps that’s the wrong question to ask. Instead of “Where was Atlantis?”, we might ask, “What kinds of civilizations might have been lost that inspired such stories?”

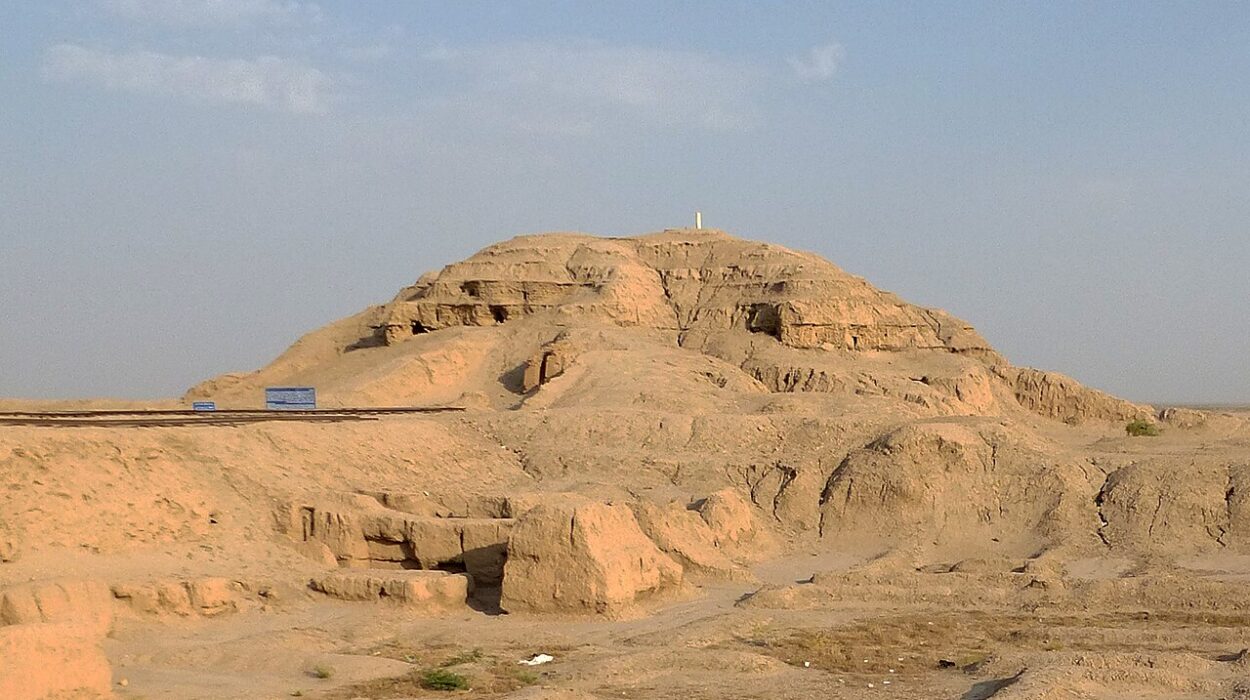

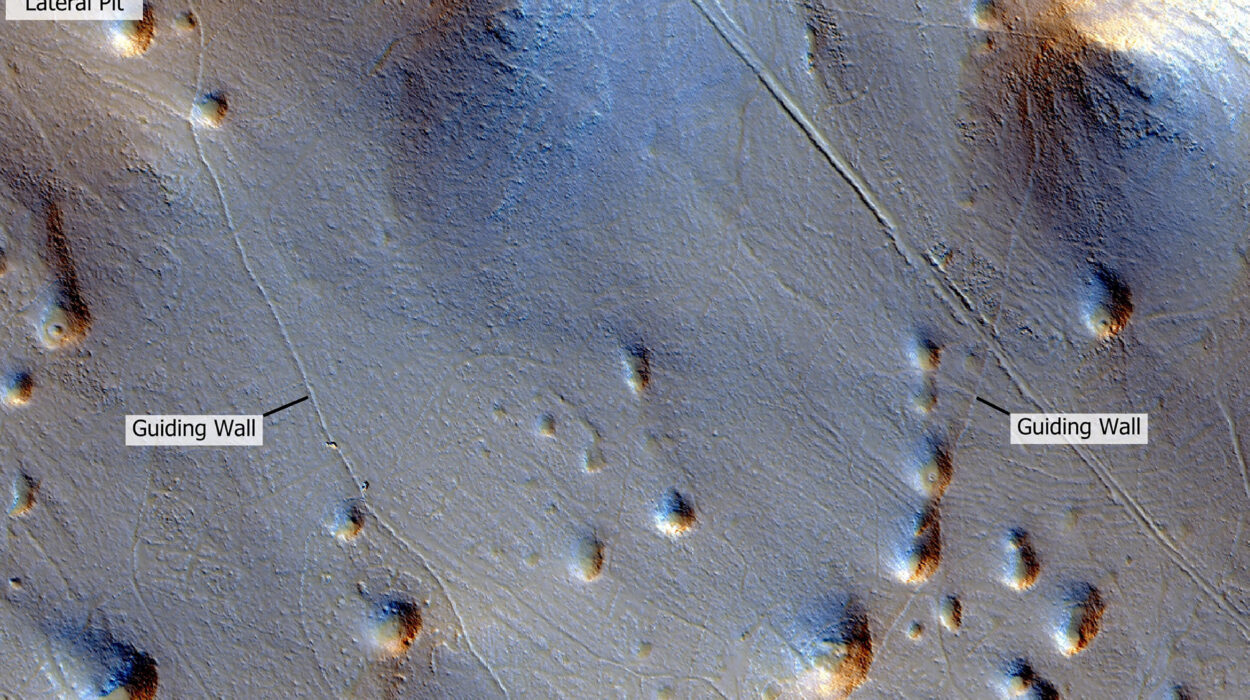

Archaeology constantly reveals that human society was far more interconnected and advanced than once believed. Sites like Göbekli Tepe, built over 11,000 years ago in modern-day Turkey, challenge old assumptions about the timeline of complex societies. Underwater archaeology is still in its infancy; we have explored more of Mars than the ocean floor. Who knows what ancient cities may lie drowned beneath the sea?

The people of Atlantis may never have been a single people, in a single place. They may represent a tapestry of human loss—civilizations lost to water, time, and memory, stitched together into a single haunting myth.

The Spiritual and Psychological Atlantis

Beyond the physical, Atlantis also occupies a symbolic realm. To some, it represents the Golden Age—the idea that long ago, humanity lived in harmony with nature, guided by wisdom and higher purpose. To others, it is a cautionary tale about technology and power unmoored from ethics.

Carl Jung, the father of analytical psychology, saw Atlantis as an archetype—a symbol arising from the collective unconscious. It was not a place but a shared memory of paradise lost. In this view, Atlantis is not out there waiting to be found—it is inside us, a reminder of the heights we can achieve, and how easily we can fall.

This may be why the Atlantis myth endures even when others fade. It speaks to something primal in us—the yearning for a better world, the fear of losing it, and the hope that we might reclaim it someday.

Tragedy, Not Fantasy

If we strip away the crystal pyramids and flying machines of modern Atlantis lore, what remains is still extraordinary. The story of a people, advanced for their time, who built thriving cities, understood the seas, traded across great distances—and then were destroyed, not by war, but by the indifferent forces of the earth.

Their descendants, if any survived, would have fled to other lands, their knowledge scattered like embers in the wind. Perhaps they told their children about the night the sea came. Perhaps those stories were carried west to Iberia, south to Africa, or east to Greece. A thousand years later, Plato heard a version of them and gave it a name.

That makes the myth of Atlantis not fantasy, but tragedy. A very human one.

What We Still Seek

Our fascination with Atlantis reveals much about ourselves. We are not just searching for a sunken city—we are searching for proof that greatness once existed before us, and perhaps could again. We are drawn to the idea that knowledge, lost and buried, might one day be recovered. That our ancestors were not primitive brutes, but dreamers and builders like us.

In a world increasingly threatened by climate change, rising seas, and geological unrest, the Atlantis story takes on new relevance. It is no longer just about what happened long ago, but what could happen again. Are we repeating the same mistakes—placing pride and power above balance and humility? Will future generations look back at us and tell stories of the great civilization that fell?

Atlantis, then, is more than a mystery to be solved. It is a mirror we hold to ourselves.

The Ocean’s Silence

The sea, as always, keeps its secrets. It covers half the world in darkness and pressure, hiding more history than we dare imagine. If the people of Atlantis once walked this Earth—whether on Thera, in the Caribbean, or along some forgotten coastline—then their bones are deep beneath silt and salt.

And yet, their story lives on. Not in artifacts or ruins, but in the minds of those who wonder.

The question of Atlantis is not only about what we lost, but about what we choose to remember.

Perhaps that is its greatest truth: civilizations come and go, but stories endure. And in the story of Atlantis, we hear not only the echo of a vanished people—but the enduring voice of humanity itself, calling across time, reminding us that nothing is too great to fall, and nothing too lost to be imagined again.