In the quiet soil of central China, beneath layers of earth that have kept secrets for millennia, scientists have uncovered traces of humanity’s earliest stories — not in scrolls or stones, but in the fragile code of DNA.

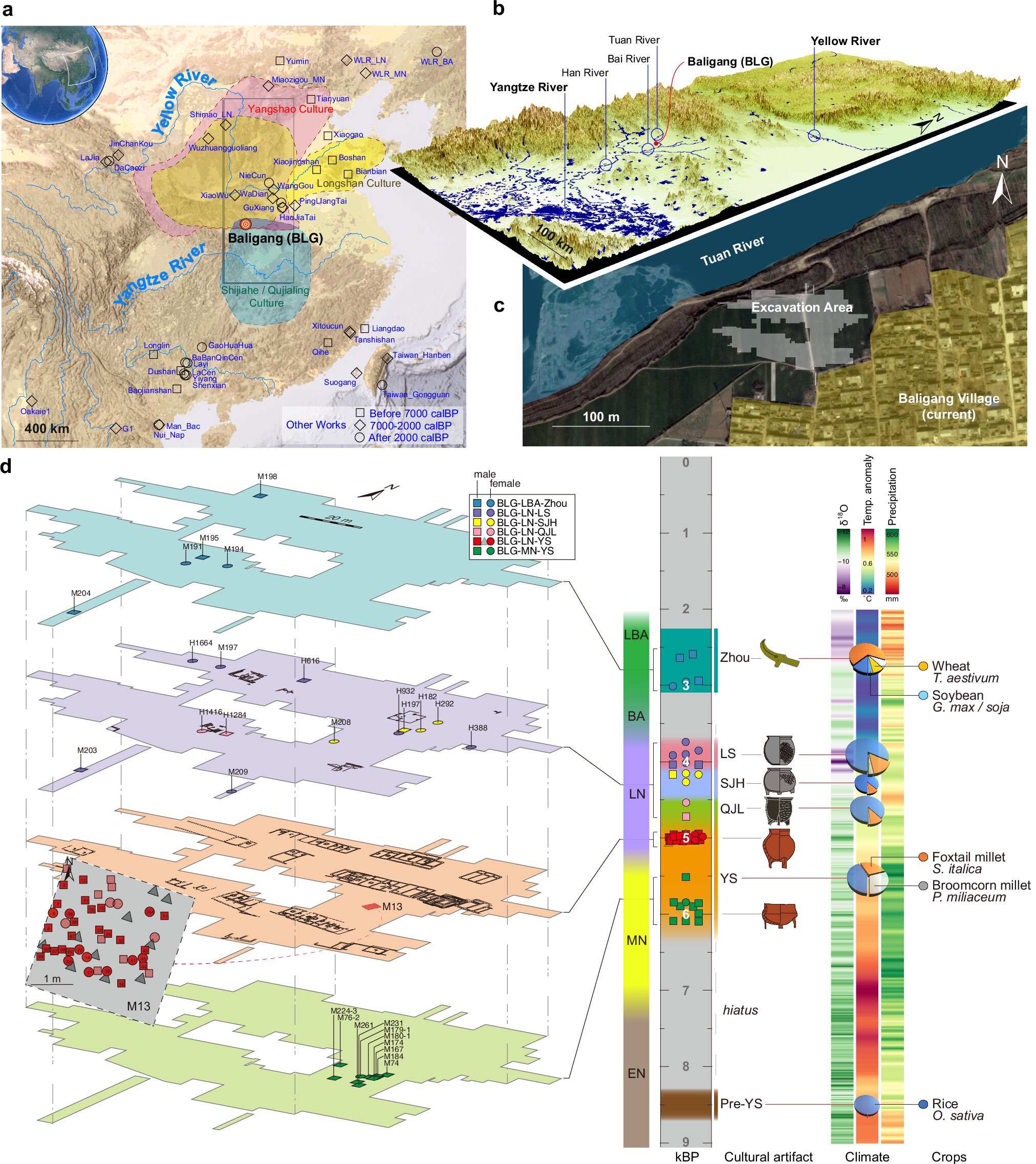

At the Baligang archaeological site in Henan Province, a team of researchers from Peking University, Yunnan University, and Minzu University of China has revealed something extraordinary: the first direct genetic evidence of a patrilineal society in Neolithic China.

Published in Nature Communications on September 30, 2025, this groundbreaking study, led by Professors Huang Yanyi and Pang Yuhong from Peking University’s Biomedical Pioneering Innovation Center (BIOPIC), goes beyond artifacts and pottery. It dives into the very biology of our ancestors, showing how prehistoric people interacted, migrated, and built the foundations of one of the world’s oldest continuous civilizations.

The Rivers That Gave Birth to a Civilization

To understand the significance of this discovery, one must return to the rivers that cradle China’s ancient past. The Yellow River in the north, with its golden silt and windswept plains, nurtured early millet-farming cultures. To the south, the Yangtze River’s humid valleys fostered the cultivation of rice.

For thousands of years, these two cradles of agriculture existed side by side — distinct yet deeply connected. The people who lived along their banks exchanged technologies, goods, and, as it turns out, their very genes. But how these early communities blended, adapted, and organized themselves socially has remained one of the great mysteries of Chinese prehistory.

Nestled between these two great river systems lies Baligang — a bridge between worlds. Archaeologists have long recognized its importance: continuous human settlement from about 8,500 to 2,500 years ago, evidence of shifting diets from rice to millet, and traces of evolving pottery styles that marked cultural transitions. Yet, until recently, the story told by bones and tools was incomplete. The missing piece was genetic evidence — the biological imprint of migration, marriage, and ancestry.

Reading the Ancient Code

Using cutting-edge ancient DNA technology, the research team extracted and sequenced the genomes of 58 ancient individuals buried at Baligang, spanning from the Middle Neolithic to the Late Bronze Age. Recovering DNA from remains thousands of years old is no small feat; time, humidity, and soil acidity often destroy genetic material. Yet, through careful preservation and advanced sequencing techniques, the team managed to reconstruct genetic histories long thought lost.

The results were stunning. Even in the early Neolithic period, the Baligang population carried a blend of northern and southern East Asian ancestry — genetic evidence that people from both millet-farming and rice-farming regions had already begun to mix. Over the centuries, the proportions of these ancestries shifted, but intriguingly, not always in ways that matched changes in material culture.

In other words, when pottery styles or farming techniques changed, it didn’t necessarily mean that new people had arrived. Cultural ideas could spread without mass migrations. Innovation, it seemed, often traveled faster than genes.

The Echo of Climate and Migration

Around 4,200 years ago, a global climate event disrupted life across continents. In Mesopotamia, drought contributed to the fall of empires. In Egypt, the Nile’s floods faltered. And in China, environmental stress reshaped ancient communities.

The Baligang genetic data shows that during this period, southern ancestry became more prominent — suggesting that rice-farming populations, pressured by changing environments, moved northward. These migrations weren’t invasions, but gradual movements of families seeking stability. The earth’s climate was rewriting the map of human genetics, one generation at a time.

The Hidden Story Beneath the Burial Ground

Among all the discoveries, one site stood out: the M13 collective burial. Inside were the remains of more than 90 individuals, a haunting yet illuminating testament to communal life in Neolithic China.

When researchers examined the DNA of 75 individuals, they found something astonishing. Every man buried there shared the same Y-chromosome lineage — passed down from father to son — while the women carried a variety of maternal lineages.

This pattern revealed a clear social structure: the community followed a patrilineal and patrilocal system. Men stayed in their birthplace, inheriting their father’s lineage and land. Women, meanwhile, came from other groups, joining through marriage. Together, they formed extended kin-based settlements where ancestry, inheritance, and identity were bound to the male line.

Modeling suggested that this burial represented a single male kin group of more than 200 individuals — one of the earliest and most concrete examples of a patrilineal social organization identified through DNA in East Asia.

What these genetic relationships tell us is not just about biology, but about belonging. They paint a vivid picture of a community bound by blood, loyalty, and shared memory — where men built and maintained their ancestral homes, and women brought new connections, weaving social networks across different villages.

Genes as Witnesses to Culture

The Baligang study shows how genetics can illuminate history in ways archaeology alone cannot. Pottery fragments, tools, and dwellings tell us how people lived, but DNA reveals who they were and how they were related.

The discovery that cultural styles and genetic patterns didn’t always align also challenges old assumptions. In the past, archaeologists often interpreted changes in material culture — new pottery designs or shifts in farming — as evidence of migrations or population replacement. But at Baligang, genetics shows that ideas could spread through trade, imitation, and communication rather than mass movement.

Biology, it seems, confirms what anthropology has long suggested: culture is a dialogue, not a conquest.

A Civilization Woven from Diversity

By the time Chinese civilization began to take recognizable shape along the Yellow River — the time of the Longshan culture and early states — the people living there were already genetically diverse. The fusion of northern and southern ancestries created not a uniform population, but a dynamic mosaic.

This diversity may have been one of China’s greatest strengths. Communities that blended different traditions were better equipped to adapt — to new crops, shifting climates, and emerging technologies. Over generations, these early interactions laid the foundation for a civilization that prized unity in diversity, balance in contrast, and harmony in difference.

The Baligang DNA thus echoes a timeless truth: civilizations are not born from isolation, but from connection.

A Window into the Ancient Family

What does it mean to find a patrilineal society in the DNA of 4,000-year-old bones? For one, it tells us that family and identity were already central to how early Chinese communities were structured. Kinship wasn’t just social — it was spatial and genetic.

In such systems, land and labor passed down the male line. Family tombs, like the M13 burial, served as symbols of continuity. Even in death, people reaffirmed their belonging to a lineage. The women who joined from outside didn’t erase their origins; they linked one community to another, spreading culture and genes alike.

It is humbling to think that the ancient patterns uncovered at Baligang — men staying, women marrying out — echo in social customs that persisted for thousands of years. The DNA whispering from those graves speaks of the deep roots of Chinese kinship traditions that shaped society long before written history began.

Science as a Bridge Between Past and Present

This study stands as a model of modern interdisciplinary research. By combining archaeology, genetics, climatology, and anthropology, scientists can reconstruct not just the events of prehistory, but the lived experiences of real people.

It also marks a milestone for ancient DNA studies in Asia. Once limited by preservation challenges, researchers in China now have the tools and technology to reveal the continent’s deep genetic history. Each discovery refines our understanding of where we came from — and how human societies evolved through cooperation, migration, and adaptation.

Beyond Borders: A Global Perspective

While this research focuses on China, its implications stretch far beyond Asia. Similar patterns of social organization have been found in prehistoric Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Across the world, early farming communities often developed kin-based networks that balanced cooperation and competition, stability and change.

The Baligang findings remind us that the roots of civilization — family, culture, migration, resilience — are universal. Every society carries within its DNA a record of how its people learned to live together, adapt to the Earth’s moods, and pass on not just their genes, but their stories.

The Legacy of the Ancestors

In the end, the discovery at Baligang is more than a scientific breakthrough — it is a human one. It reconnects us with people who lived thousands of years ago, who loved, worked, raised families, and faced uncertainty in a changing world.

Their genetic code, preserved in ancient bones, is a bridge across time. It tells us that we are all part of an unbroken continuum — the living descendants of countless generations who endured, adapted, and dreamed.

The story of Baligang is not just about China’s beginnings; it is about what makes us human. Across ages and continents, the desire to belong, to protect family, to build and to remember — these are threads woven through every civilization.

In their DNA, the people of Baligang left us a message: that even as cultures shift and climates change, the essence of humanity — connection, resilience, and love — endures. And through science, we can finally listen to those ancient voices, echoing softly through time.

More information: Tingyu Yang et al, Ancient DNA reveals the population interactions and a Neolithic patrilineal community in Northern Yangtze Region, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-63743-1