For decades, the Iberian Peninsula has felt like a quiet threshold in human history. A place where continents narrow, climates collide, and ancient paths converge. Somewhere in that vast landscape of stone, wind, and shifting ice, two kinds of humans may have stood within reach of each other. One was already fading. The other was just beginning to spread its footprint across Europe. Whether they ever met has remained one of the most haunting unanswered questions of the Paleolithic world.

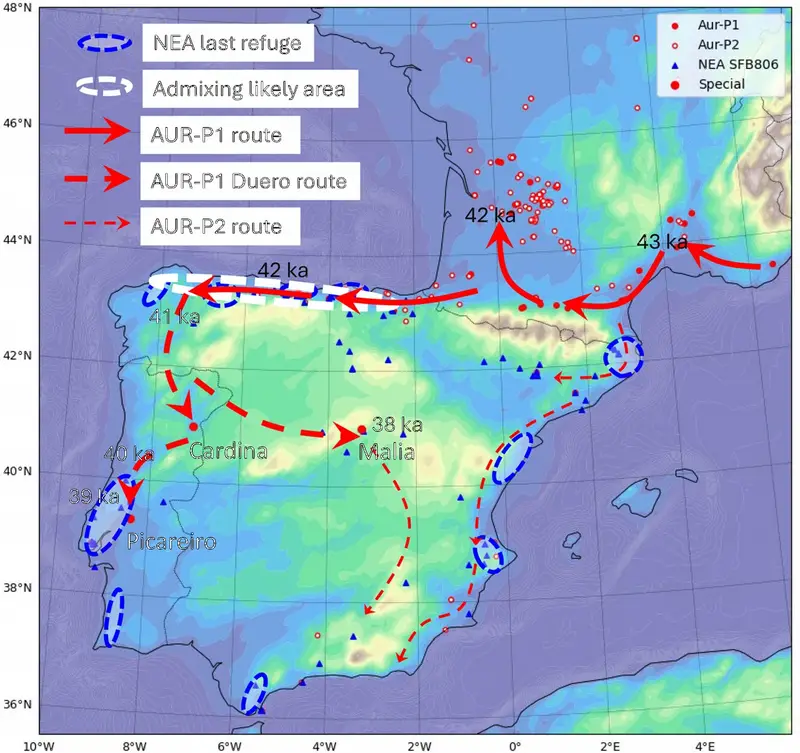

Now, researchers at the University of Cologne have taken a bold step into that uncertainty. Using a specially developed simulation model, they have traced and analyzed the possible encounters between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans on the Iberian Peninsula during the Paleolithic period for the first time. Not through bones alone, not through scattered tools or fragmentary dates, but through a dynamic reconstruction of movement, climate, and survival unfolding over thousands of years.

The result is not a simple answer. It is a story of fragile populations, harsh climates, missed connections, and rare moments when paths might have crossed.

When Modern Humans Entered a Neanderthal World

Between approximately 50,000 and 38,000 years ago, anatomically modern humans arrived in Europe. They did not enter an empty land. Neanderthals had already lived there for hundreds of thousands of years, adapted to cold climates and rugged terrains. The Iberian Peninsula, in particular, is thought to have been one of the last refuges where Neanderthal populations persisted while disappearing elsewhere.

The research team set out to understand what happened when these two human groups shared the same continent. They asked whether their settlement areas overlapped, how they might have moved across the landscape, and whether the timing of their presence allowed for encounters. Beneath those questions lay something deeper. Did they interact? Did they mix? Or did they pass through time like ships in a fog, close but never touching?

The study, titled “Pathways at the Iberian crossroads: Dynamic modeling of the Middle-Upper Paleolithic Transition,” was led by Professor Dr. Yaping Shao from the Institute of Geophysics and Meteorology and published in the journal PLOS One. It was conducted within the framework of the HESCOR research project at the University of Cologne, in collaboration with Professor Dr. Gerd-Christian Weniger (Emeritus) of the Department of Prehistoric Archaeology.

A New Way of Looking at Ancient Lives

Traditional archaeology and genetics offer powerful tools, but they often struggle with gaps in time and space. Bones are rare. Dates carry uncertainties. Landscapes change. To move beyond these limitations, the researchers turned to simulation.

They used a numerical model designed to explore the possibility of both groups meeting on the Iberian Peninsula. The model does something unusual. It does not freeze the past into a single scenario. Instead, it allows history to unfold in many possible ways.

Climate fluctuations are built into the model, along with population sizes, movement patterns, connectivity, and potential interaction between groups. This allows the researchers to test a wide variety of scenarios dynamically, rather than relying on fixed assumptions.

“By linking climate, demography, and culture, our dynamic model offers a broader explanatory framework that can be used to better interpret archaeological and genomic data,” says Professor Weniger from the Department of Prehistoric Archaeology.

The model becomes a kind of time machine, not claiming certainty, but exploring plausibility. It asks what could have happened, given what we know, and what the limits of those possibilities might be.

A World Shaped by Ice and Sudden Warmth

The period in question was anything but stable. During the transition from the Middle to the Upper Paleolithic, Neanderthal populations across Europe experienced a steady decline that eventually led to their extinction. At the same time, anatomically modern humans were spreading across the continent.

All of this unfolded against a backdrop of intense climatic instability. The climate oscillated between cold and warm phases. Some warming phases occurred rapidly, over just a few centuries, while cooling periods were more gradual. These patterns, known as Dansgaard–Oeschger events, were punctuated by even harsher episodes called Heinrich events, when massive iceberg discharges into the North Atlantic triggered severe cold phases.

For human populations already living close to survival limits, these fluctuations mattered deeply. A sudden cold snap could shrink habitable land, reduce resources, and isolate groups. A brief warming could open new corridors and opportunities for movement.

The model shows that populations during this time were highly sensitive to these climatic shifts. Survival was not just a matter of tools or culture, but of timing and resilience in the face of environmental change.

The Vanishing of the Neanderthals and the Question of Meeting

One of the most persistent mysteries is the precise timing of Neanderthal extinction relative to the arrival of modern humans. The dates overlap, but not cleanly. This uncertainty leaves open the possibility that the two groups may have encountered each other on the Iberian Peninsula.

Genetic analyses of bones from archaeological excavations, compared with today’s populations, indicate that mixing occurred in Eastern Europe during the early migration phases of modern humans. Whether similar mixing happened later in Iberia is still unknown. Dating uncertainties make it possible, but no direct evidence has yet confirmed it.

The simulation model allows researchers to explore this uncertainty rather than ignore it. By running the model repeatedly with different parameters, they can see which scenarios are plausible and which are unlikely.

Paths That Rarely Crossed

“Repeated runs of the model with different parameters allow for an assessment of the plausibility of different scenarios: an early extinction of the Neanderthals, a small population size with a high risk of extinction, or a prolonged survival that would allow mixing,” says Professor Shao, principal investigator of the study.

In most of the simulations, the two groups did not meet at all. Their populations moved, shrank, or expanded in ways that kept them apart in space or time. This suggests that, even if both groups lived on the Iberian Peninsula during overlapping periods, direct encounters may have been rare.

Yet the model does not close the door entirely. In scenarios where Neanderthal populations remained stable long enough, mixing became possible. These cases were sensitive to climate, geography, and timing.

With a low probability of about 1%, the simulations ended with small proportions of the population carrying genes from both groups. These proportions ranged from 2–6% of the total population. Such mixing would have been most likely in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, where modern humans could have arrived early enough before Neanderthal populations collapsed completely.

These results do not claim that mixing definitely occurred there. Instead, they show that under certain conditions, it could have happened.

Beyond Humans Alone

The research does not stop with these findings. The team is already looking ahead, planning to improve both the numerical model and the potential field required for it. One key limitation of current simulations is that they focus primarily on human populations.

In future studies, the researchers plan to include animals that could serve as potential prey. This addition matters because human movement and survival are closely tied to available resources. To achieve this, vegetation data will be fed into a potential field calculated separately for humans and animals, using a variety of climatic and geographical data.

The team is also investigating whether a specialized machine learning algorithm could help refine these simulations further, opening new ways to explore ancient population dynamics with greater precision.

Why This Story Matters

This research matters because it reshapes how we think about one of the most pivotal moments in human history. The question of whether Neanderthals and modern humans met is not just about curiosity. It touches on identity, resilience, and the complex pathways that led to the world we inhabit today.

By using dynamic modeling, the researchers show that history is not a single fixed line. It is a landscape of possibilities shaped by climate, chance, and fragile survival. The disappearance of the Neanderthals was not simply inevitable, nor was contact with modern humans guaranteed.

This study reminds us that human history unfolded under pressures we can barely imagine, where small changes in climate or timing could mean the difference between extinction and survival, isolation and connection.

In tracing these ancient pathways, the researchers offer something more than answers. They offer a deeper appreciation of how uncertain, complex, and profoundly human our past truly is.

More information: Yaping Shao et al, Pathways at the Iberian crossroads: Dynamic modeling of the middle–upper paleolithic transition, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0339184