Four hundred thousand years ago, long before the rise of cities, art, or written language, the Italian landscape looked very different. Vast grasslands rolled beneath a warm Middle Pleistocene sun, scattered with patches of woodland and winding rivers. Herds of immense straight-tusked elephants — Palaeoloxodon antiquus — roamed these open plains, their heavy steps echoing across the ancient earth. And watching them from a distance were small bands of humans, our distant ancestors, whose survival depended on the land and the creatures that shared it.

A new study published in PLOS One on October 8, 2025, has breathed life into this long-lost world. Led by Beniamino Mecozzi of Sapienza University of Rome, researchers uncovered extraordinary evidence of human ingenuity and adaptation at a site called Casal Lumbroso in northwest Rome. There, they found the skeletal remains of a single massive elephant, along with more than 500 stone tools — the traces of a moment frozen in prehistoric time when humans and giants met in an encounter of survival.

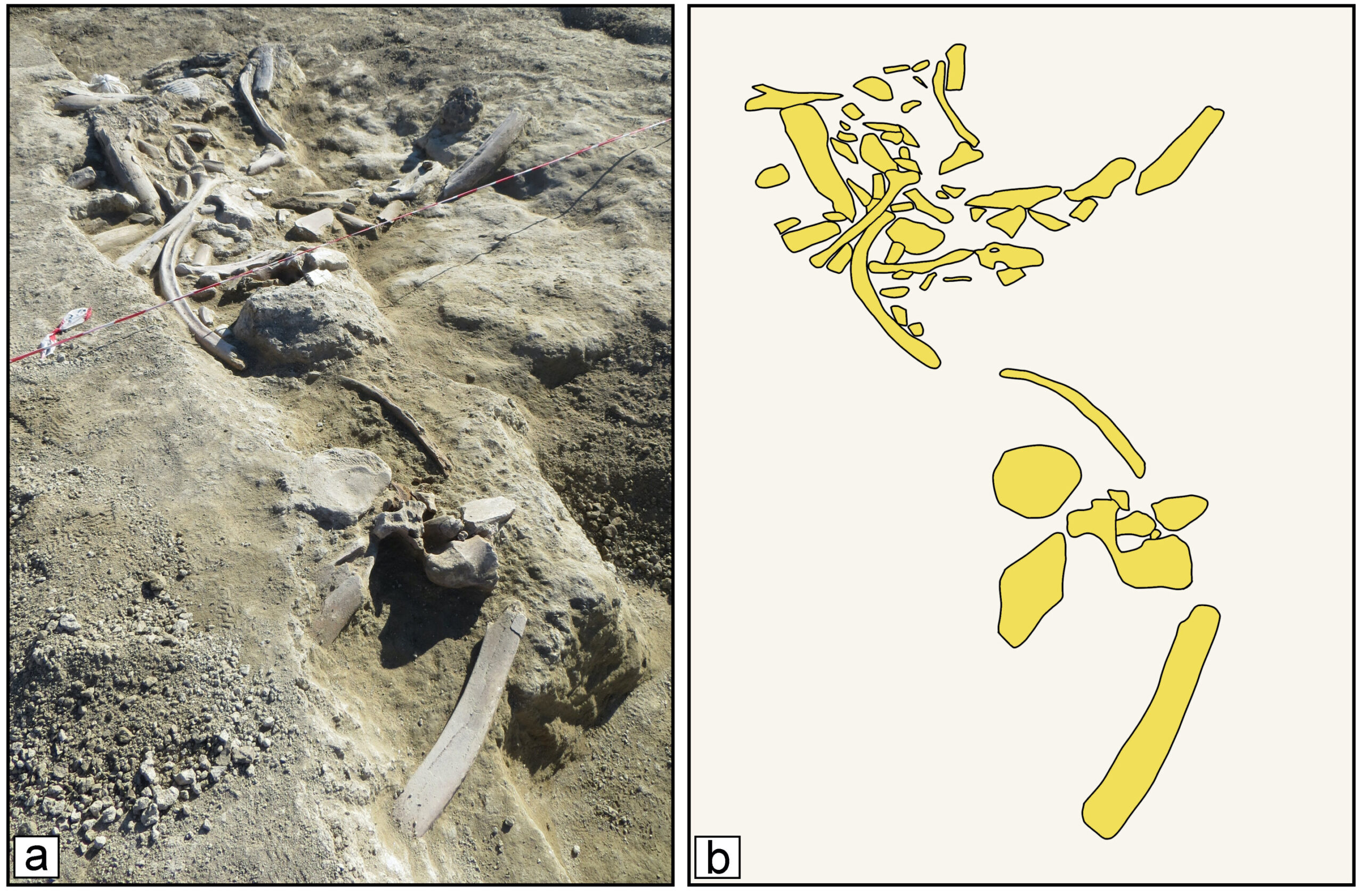

Unearthing the Ancient Feast

The discovery at Casal Lumbroso offers a vivid glimpse into how early humans lived during a particularly warm period of the Middle Pleistocene, around 404,000 years ago. The team identified over 300 fragments from the skeleton of a single Palaeoloxodon — a species of straight-tusked elephant that could weigh up to 13 tons, nearly twice as much as today’s African elephants.

Scattered among the bones lay a treasure trove of more than 500 stone tools, most of them surprisingly small — many less than three centimeters long. These tiny tools might seem unimpressive at first glance, but in the hands of resourceful humans, they became instruments of survival. The researchers believe they were used to carve meat from the elephant’s enormous carcass and extract the rich marrow hidden within its bones.

What’s remarkable is what was missing: deep cut marks or slicing grooves typically left behind by large, sharp tools. Instead, the bones bore blunt impact marks and fractures — signs that ancient humans struck them with forceful blows soon after the animal’s death. This suggests a butchery process that relied more on percussive techniques and small cutting edges than on large, finely crafted blades.

Tools from the Bones of Giants

The study also revealed that humans didn’t stop at consuming the elephant’s meat. Several of the elephant’s bones themselves were modified into tools — transformed from the remains of a meal into instruments for future survival. In the absence of larger stones, which were scarce in the region, these early Italians adapted by turning bone into technology.

Such resourcefulness speaks volumes about the intelligence and adaptability of Middle Pleistocene humans. They didn’t waste. Every part of the elephant was valuable: meat to feed their community, fat for fuel, hide for coverings, and bones for crafting. This was not mindless scavenging — it was strategy, precision, and an understanding of the materials the Earth provided.

A Shared Strategy Across Ancient Italy

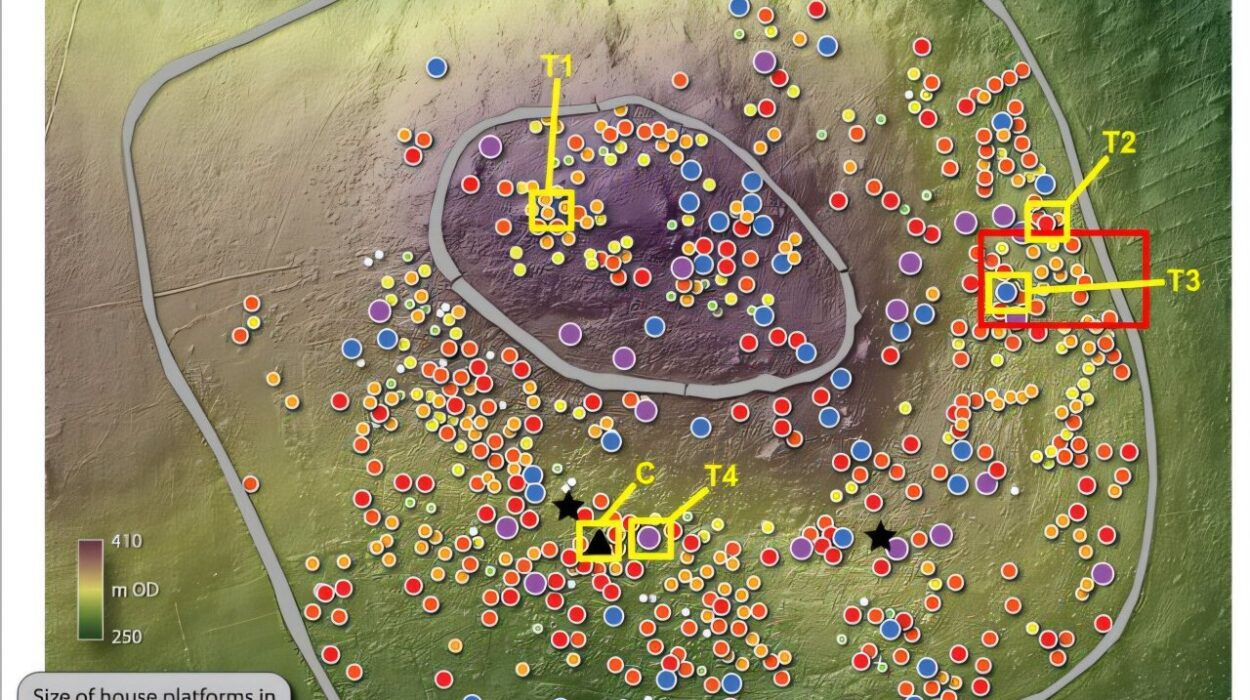

The Casal Lumbroso site is not an isolated case. Similar evidence has been uncovered at other Middle Pleistocene sites in central Italy, showing a consistent pattern. Butchered elephant remains, modified bones, and small stone tools have been found together at multiple locations, suggesting that this was a well-established strategy among early humans living in the region.

This pattern paints a picture of communities that flourished during warmer intervals — times when elephants and other large animals roamed freely across fertile landscapes. These ancient humans were not passive scavengers living on leftovers; they were active participants in the ecosystem, capable of exploiting massive resources when the opportunity arose.

The study’s authors describe this discovery as a window into a vanished world — a time when humans, animals, and climate were locked in an intricate dance of survival and adaptation.

Life in the Middle Pleistocene

To imagine these events, we must first understand the world these humans inhabited. The Middle Pleistocene, which spanned from about 780,000 to 125,000 years ago, was a time of fluctuating climates — alternating glacial and interglacial periods that transformed the face of Europe again and again. During warmer intervals, Italy was a refuge of abundance, a safe haven for both animals and humans.

The humans of this era were likely early members of the species Homo heidelbergensis, an ancestor of both Neanderthals and modern humans. They were intelligent, social, and capable of complex behavior. Their lives were defined by adaptation — building tools from whatever they could find, using fire to cook and protect themselves, and forming tight-knit groups that hunted, shared, and survived together.

For these humans, an elephant carcass represented an extraordinary windfall — a single animal could provide food for weeks, perhaps months, as well as valuable materials for tools and shelter. But accessing this resource wasn’t easy. Whether they hunted the elephant or scavenged it after a natural death, processing such a colossal creature required planning, cooperation, and courage.

Reading the Marks of Time

Archaeologists have become detectives of deep time. At Casal Lumbroso, every fracture and groove on the elephant’s bones tells part of the story. Fresh fractures reveal that the bones were broken soon after death — when they were still moist and pliable. The patterns of damage indicate intentional strikes rather than random natural forces.

The ash deposits found nearby helped researchers date the event to around 404,000 years ago. This precise dating, achieved through comparative analysis with other sediment layers, confirms that the butchery occurred during a warm phase of the Middle Pleistocene. Such warm periods encouraged lush vegetation and attracted herds of large animals — and in turn, the humans who followed them.

Reconstructing a Prehistoric Scene

Picture the scene: an open landscape under a golden sky. A small group of early humans approaches the carcass of a fallen elephant — perhaps brought down by age, injury, or coordinated effort. They work together, communicating with gestures and simple sounds. Some strike the bones with stones, cracking them open for marrow. Others use sharp-edged flakes to slice through thick flesh.

The air smells of smoke and blood. The earth is littered with flakes of stone, each one the result of a human hand shaping a tool. Nearby, children might watch and learn, imprinting the techniques that would one day keep their own families alive. For these people, the elephant is not just food — it is survival embodied, a gift from the land that sustains them.

A Testament to Human Ingenuity

The study’s lead author, Beniamino Mecozzi, put it beautifully: “Our study shows how, 400,000 years ago in the area of Rome, human groups were able to exploit an extraordinary resource like the elephant—not only for food, but also by transforming its bones into tools. Reconstructing these events means bringing to life ancient and vanished scenarios, revealing a world where humans, animals, and ecosystems interacted in ways that still surprise and fascinate us today.”

Indeed, what makes discoveries like Casal Lumbroso so powerful is not just the evidence of butchery, but what it tells us about the people behind it. These were not primitive brutes. They were problem-solvers, innovators, and survivors — shaping their world through creativity and collaboration.

The Legacy of the Butchers of Casal Lumbroso

The humans who lived and worked at Casal Lumbroso are long gone, their bones turned to dust and their voices lost to time. Yet their actions endure in the fragments they left behind — a broken tusk, a stone flake, a fractured bone. Through these remnants, we see echoes of ourselves: the same hunger, curiosity, and ingenuity that have defined our species since its dawn.

The elephants they butchered no longer roam Italy’s hills, and the warm Pleistocene winds have cooled into modern temperate breezes. But the story unearthed in the soil near Rome reminds us that even in the deepest reaches of prehistory, humans were already shaping their destiny — one stone, one meal, one discovery at a time.

More information: From meat to raw material: the Middle Pleistocene elephant butchery site of Casal Lumbroso (Rome, central Italy), PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0328840