A thousand years ago, in the rugged mountains of Zimapán, Mexico, a man lived, walked, hunted, and dreamed — unaware that centuries later, his body would whisper secrets to science. His remains, wrapped carefully in woven maguey fibers and native brown cotton, were laid to rest in a rock shelter by his people, the ancient Otopame. To them, he may have been a respected member of the community, honored in death as he had been in life.

To modern scientists, he has become something equally remarkable: a time capsule of biology. Within his mummified remains lies not just his body, but an invisible world — his microbiome — preserved across the centuries like a message from the past. And now, through delicate molecular analysis, researchers have begun to read that message, uncovering what life — and health — may have looked like in pre-Columbian Mexico.

The Hidden Universe Inside Us

Every human being carries an inner world teeming with life. Trillions of microorganisms — bacteria, viruses, fungi, and archaea — inhabit our intestines, forming what scientists call the gut microbiome. Though microscopic, this vast ecosystem shapes nearly every aspect of our existence. It helps digest food, produces essential vitamins, strengthens the immune system, and even influences mood and behavior.

Yet the microbiome is not static. It shifts with diet, environment, and culture, reflecting how humans live and what they eat. For modern humans, processed foods, antibiotics, and urban lifestyles have dramatically altered this internal world. By studying ancient microbiomes, scientists can trace how these changes unfolded — offering a biological record of human evolution, migration, and adaptation.

A Window Into Ancient Mexico

Santiago Rosas-Plaza and colleagues from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México recently opened that window wider than ever before. Publishing their findings in PLOS One, the team analyzed the preserved feces and intestinal tissue of the “Zimapán man,” who lived about 1,000 years ago — long before European contact reshaped the Americas.

Earlier studies suggested that this young man, aged between 21 and 35 at the time of his death, was a seminomadic hunter-gatherer of the Otopame culture. His people roamed the dry highlands of central Mexico, relying on hunting, gathering, and perhaps early agriculture. What he ate, the water he drank, and the air he breathed all influenced the microscopic community that lived within him — and astonishingly, that microbial world survived the centuries sealed in his remains.

Using a powerful genetic technique called 16S rRNA sequencing, the researchers identified the bacterial DNA preserved in his intestines and feces. The results illuminated not only the Zimapán man’s inner ecosystem but also how his microbiome compared to that of modern humans.

The Ancient Bacterial Blueprint

Among the bacterial families identified were Peptostreptococcaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, and Enterococcaceae — all commonly associated with the human gut. These bacteria would have helped digest food, break down complex plant materials, and protect against harmful microbes. Their presence suggests that, despite the gulf of centuries, some elements of the human microbiome have remained remarkably consistent.

But there were surprises as well. High levels of Clostridiaceae bacteria were found, mirroring results from other ancient Andean mummies. These bacteria thrive in low-oxygen environments like the human gut and may have been central to the digestion of traditional ancient diets rich in natural fibers.

Even more intriguing was the discovery of Romboutsia hominis — a bacterium associated with the modern human gut but never before detected in an ancient microbiome. Its presence bridges the past and present, hinting that certain bacterial lineages have endured through millennia, adapting to human lifestyles as we evolved.

Tracing a Life Through Microbes

The bacteria found in the Zimapán man’s body are more than names on a genetic chart; they are evidence of how he lived. The dominance of fiber-digesting microbes, for instance, implies a diet composed mainly of plants, roots, and perhaps unprocessed grains — consistent with a seminomadic lifestyle. The absence of microbes commonly linked to high-fat or sugar-rich diets suggests that his world was untouched by the modern dietary revolution.

Each bacterial trace tells a story. The balance of microbes may reveal the region’s ecology — its soil, water, and climate. Some bacteria might have entered his system through fermented foods or the natural environment, reflecting the tight bond ancient peoples had with the land. Others could indicate the man’s health or even the conditions surrounding his death.

By studying his microbiome, scientists can reconstruct more than just biology; they can glimpse his world — what he ate, where he lived, and how his people’s relationship with nature shaped their health and survival.

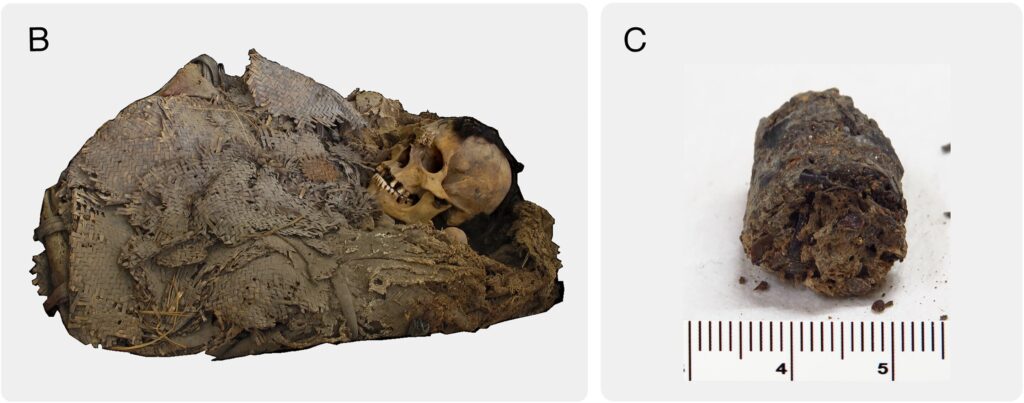

The Sacred Bundle and Its Secrets

The Zimapán man’s body was not simply buried — it was honored. Wrapped like a sacred bundle, he was laid within a mat woven from maguey fibers, covered by an exquisitely crafted sheet of native brown cotton. Researchers studying the fabric discovered a complex mathematical pattern in its knots, suggesting careful craftsmanship and cultural significance.

According to the team, such an arrangement could indicate that he was a person of importance — perhaps a hunter, a leader, or a respected member of his community. For nearly a decade, restoration expert Master Luisa Mainauo and her team have worked to preserve the bundle. Their goal is to one day share it with the people of Mexico and the world — allowing the Zimapán man to be seen not just as an archaeological specimen, but as a person whose story bridges the ancient and the modern.

Why Ancient Microbiomes Matter

At first glance, studying 1,000-year-old intestinal bacteria might seem like an obscure pursuit. But the implications stretch far beyond archaeology. Ancient microbiome research offers a unique window into human history, health, and evolution.

By comparing ancient and modern microbiomes, scientists can trace how industrialization, antibiotics, and changing diets have reshaped our internal ecosystems. Some modern diseases — allergies, obesity, autoimmune disorders — may be linked to the loss of microbial diversity that once protected ancient humans. Understanding what our ancestors’ microbiomes looked like could help modern medicine restore that balance.

Moreover, studying ancient bacteria reveals how microbes themselves evolved alongside us — a co-evolutionary partnership that has defined our species since its origins. The Zimapán man’s microbiome thus becomes part of a much larger story: the deep-time relationship between humans and the unseen life that sustains us.

Preserving the Past, Illuminating the Future

The discovery from Zimapán is not just a scientific milestone; it is a bridge across time. It connects modern Mexico to its pre-Columbian heritage, reminding us that science and culture are intertwined. Every thread of the ancient cotton, every bacterial gene sequence, tells us something about who we are and where we come from.

Future analyses will aim to reconstruct the complete microbial composition of the Zimapán man’s gut. This could reveal not only dietary habits but also potential pathogens, symbiotic relationships, and even the microbiome’s role in ancient immunity. With advances in DNA sequencing, scientists can now resurrect the invisible ecosystems that once thrived within our ancestors, offering unprecedented insight into the history of life itself.

The Eternal Dialogue Between Life and Time

The Zimapán man may have died a thousand years ago, but his microbiome lives on — not as a collection of cells, but as information, as a story encoded in molecules. His gut bacteria, preserved by chance and honored by culture, have become storytellers in their own right. They whisper of a life close to the earth, of natural diets and microbial balance, of a time when humans lived in rhythm with the world that sustained them.

In studying him, we study ourselves. For though the world has changed beyond recognition, the microscopic partnerships within us remain — fragile, enduring, and vital. The Zimapán man’s final gift is a reminder that life’s history is written not only in bones and artifacts but in the smallest forms of life that accompany us from birth to death.

In those ancient microbes, we find not only the story of one man but the shared biological heritage of all humanity — a testament to how deeply, and how beautifully, the living and the dead remain connected.

More information: Microbiome characterization of a pre-Hispanic man from Zimapán, Mexico: Insights into ancient gut microbial communities, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0331137