More than 3,500 years ago, the tranquil island of Thera—now known as Santorini—was shattered by one of the most powerful volcanic eruptions in human history. The explosion tore through the island with unimaginable force, sending plumes of ash and gas high into the stratosphere and generating tsunamis that raced across the eastern Mediterranean. It was a moment of fire and fury that darkened skies, reshaped coastlines, and forever altered civilizations.

For centuries, historians and archaeologists have been captivated by this cataclysm, seeking to understand not just its magnitude, but also its timing. The eruption is believed to have contributed to the collapse of the Minoan civilization on Crete, and its aftermath may have echoed across the ancient world, influencing myths, trade, and even dynastic transitions. Yet one question lingered for generations: when, exactly, did the volcano erupt?

The Mystery of Timing

For decades, scholars debated whether the Santorini eruption took place in the late 17th or 16th century BCE. This was not merely a technical dispute—it had profound implications for understanding how ancient Mediterranean societies interacted. The eruption’s date served as a crucial chronological anchor linking Aegean and Egyptian history.

Egyptian records, with their detailed royal lineages, have long provided the backbone of Bronze Age chronology. If the Santorini eruption coincided with a particular pharaoh’s reign, it could synchronize the timelines of two major civilizations—the Egyptian and the Minoan. But despite decades of effort, archaeological evidence and radiocarbon dating failed to align neatly, leaving the question suspended in uncertainty.

A Breakthrough Beneath the Sand

Now, a groundbreaking study by researchers from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel and the University of Groningen in the Netherlands has brought new light to this ancient mystery. Their results, published in PLOS One, reveal that the colossal eruption of Thera occurred earlier than previously believed—before the dawn of Egypt’s New Kingdom.

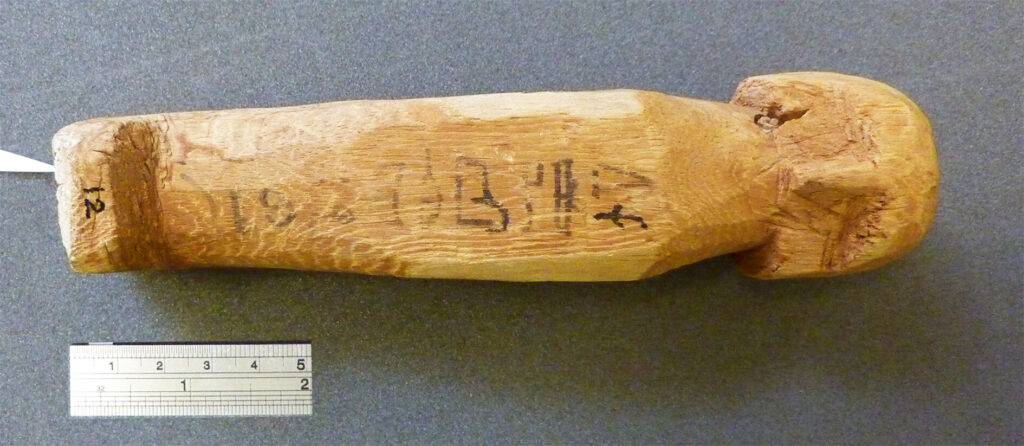

Led by Prof. Hendrik J. Bruins and Prof. Johannes van der Plicht, the research team achieved what few others had done before: they obtained permission to radiocarbon-date rare Egyptian artifacts directly linked to Pharaoh Ahmose I, the ruler who reunified Egypt after years of division. Working under close supervision at the British Museum and the Petrie Museum in London, they carefully selected and analyzed ancient samples—a mudbrick from the Ahmose Temple at Abydos, a linen burial cloth belonging to a noblewoman named Satdjehuty, and wooden shabti figurines from Thebes.

The Pharaoh and the Volcano

Pharaoh Ahmose I stands as one of ancient Egypt’s pivotal figures. His reign marked the end of the Second Intermediate Period—a time when Egypt was divided and partially ruled by foreign powers known as the Hyksos—and the beginning of the New Kingdom, a golden era of expansion, art, and power.

Until recently, many believed that the Thera eruption occurred around the same time as Ahmose’s reign, suggesting that the environmental chaos unleashed by the volcano might have indirectly influenced the political unification of Egypt. But the new radiocarbon evidence tells a different story.

According to Bruins and van der Plicht’s findings, the Santorini eruption predates Ahmose’s rule. The eruption likely occurred during the earlier Second Intermediate Period, before Egypt was reunified. This revelation shifts the timeline of Egyptian history itself, implying that the Second Intermediate Period lasted longer—and that the New Kingdom began later—than previously thought.

The Science Behind the Revelation

Radiocarbon dating is one of archaeology’s most powerful tools for measuring time. It relies on the natural decay of carbon-14, a radioactive isotope found in all living organisms. When something dies—whether a tree, an animal, or a human—the carbon-14 inside it begins to decay at a predictable rate. By measuring how much carbon-14 remains in ancient materials, scientists can estimate their age with remarkable precision.

In this case, the researchers extracted carbon-based samples—wood, cloth, and mudbrick—from objects directly tied to known historical figures. Because these materials were contemporary with Ahmose and his court, they provided an accurate radiocarbon “timestamp” for that period in Egyptian history.

The results were striking. The calibrated radiocarbon ages of these artifacts placed Ahmose’s reign—and therefore the start of the New Kingdom—decades later than traditional archaeological chronologies had suggested. Meanwhile, independent radiocarbon studies of Santorini’s eruption have consistently yielded older dates. When compared, the two datasets showed a clear gap: the eruption occurred before the rise of the New Kingdom.

Rewriting the Timeline

The implications of this discovery ripple far beyond Egypt. The synchronization of Mediterranean chronologies—the delicate web of dates linking Egypt, Crete, Cyprus, and the Levant—has always depended on accurate anchor points. If the New Kingdom began later, then all the historical connections once assumed between Egyptian and Aegean civilizations must be reconsidered.

It also reshapes our understanding of how natural disasters influenced human history. For years, some scholars speculated that the Thera eruption triggered political upheavals in Egypt by disrupting trade and agriculture. But if the eruption predates Ahmose’s unification, its role must be reinterpreted—not as a catalyst for Egypt’s rebirth, but as part of an earlier era’s unfolding chaos.

A World in Ash and Silence

To imagine the Thera eruption is to confront the raw power of nature. The island’s volcanic cone exploded with the energy of several hundred atomic bombs, sending shockwaves through the sea and air. Pyroclastic flows buried settlements beneath molten rock and ash. The sky turned black for days or weeks. In distant lands, crops may have withered under the cooling effects of volcanic aerosols.

The Minoan civilization, thriving on nearby Crete, felt the full brunt of this catastrophe. Archaeologists have found layers of pumice and ash covering Minoan buildings, along with tsunami debris along the coast. The eruption likely devastated ports and trade networks across the Aegean, weakening one of the ancient world’s most sophisticated societies.

The echoes of this disaster may have reached Egypt as well. Ancient Egyptian texts speak of periods of darkness, strange weather, and floods—phenomena that could have been inspired by distant volcanic effects. Though these records are often poetic and symbolic, they hint at a civilization aware of nature’s distant convulsions.

Bridging the Past and the Present

What makes this new study remarkable is its bridge between disciplines—archaeology, chemistry, and history working in harmony to rewrite humanity’s shared story. It is a reminder that science is not merely about collecting data; it is about seeing the invisible threads that connect our past.

Prof. Bruins and Prof. van der Plicht’s work shows how even the smallest fragments—a sliver of wood, a scrap of linen—can reshape the grand narratives of civilization. Their findings challenge long-held assumptions and open new pathways for collaboration among historians, archaeologists, and climate scientists.

The Human Story Beneath the Ash

In the end, the story of the Thera eruption is not only one of destruction—it is also one of resilience. Civilizations rose and fell, yet human creativity endured. Out of chaos came new forms of art, trade, and belief. The myths that followed—the tales of a lost island, of floods and fire, of gods angered and worlds reborn—echo the human need to find meaning in catastrophe.

Perhaps that is why the Santorini eruption continues to fascinate us. It is not just a geological event—it is a turning point in the story of humanity, a reminder of how fragile and interconnected our world has always been.

The Volcano That Still Speaks

Today, the shattered caldera of Santorini remains a hauntingly beautiful place. Tourists walk along its rim, unaware that beneath their feet lies the silent heart of an ancient catastrophe. The blue-domed churches and whitewashed houses of the island cling to cliffs formed by that long-ago explosion—a constant reminder of the power that shaped them.

Science has finally given us a clearer picture of when that eruption occurred, and in doing so, it has illuminated the dawn of the Egyptian New Kingdom, the resilience of Mediterranean societies, and the enduring dialogue between Earth’s forces and human history.

The volcano’s ashes may have long settled, but its story continues to rise—from the depths of the sea, from the dust of museums, and from the hands of those who still seek to understand how the past shaped the world we live in today.

More information: Hendrik J. Bruins et al, The Minoan Thera eruption predates Pharaoh Ahmose: Radiocarbon dating of Egyptian 17th to early 18th Dynasty museum objects, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0330702