In the heart of modern-day Osijek, Croatia, archaeologists have uncovered a haunting remnant of Rome’s turbulent past—an ancient water well concealing a mass grave. Within it lay the bones of seven men, each a silent witness to one of the most violent and uncertain chapters in Roman history.

This remarkable discovery, published in PLOS ONE, reveals a rare and deeply human glimpse into the Battle of Mursa, fought around 260 CE during the Roman Empire’s notorious Crisis of the Third Century. What began as a routine archaeological excavation turned into a story of war, identity, and survival—an ancient tragedy hidden in the depths of the earth for nearly 1,800 years.

The Crisis of the Third Century: A World in Collapse

To understand the significance of these buried soldiers, one must step back into the 3rd century—a time when the Roman Empire was crumbling from within. Between 235 and 284 CE, Rome faced political chaos, economic collapse, and relentless invasions. Emperors rose and fell in rapid succession, armies mutinied, and provinces declared independence.

In this era of upheaval, Mursa (present-day Osijek) was a frontier settlement, strategically placed along the Drava River in the province of Pannonia. The region was both a gateway and a battlefield, where Roman legions clashed with external enemies and each other in civil wars that tore the empire apart.

It was here, amid the smoke and blood of the Crisis, that a group of soldiers met their fate—now rediscovered centuries later in the dark, waterlogged confines of ancient wells.

The Team Behind the Discovery

The excavation was led by Mario Novak and his team from the Institute for Anthropological Research in Zagreb, Croatia. Their work brought together archaeology, genetics, and isotopic science to reconstruct not just how these men died, but who they were.

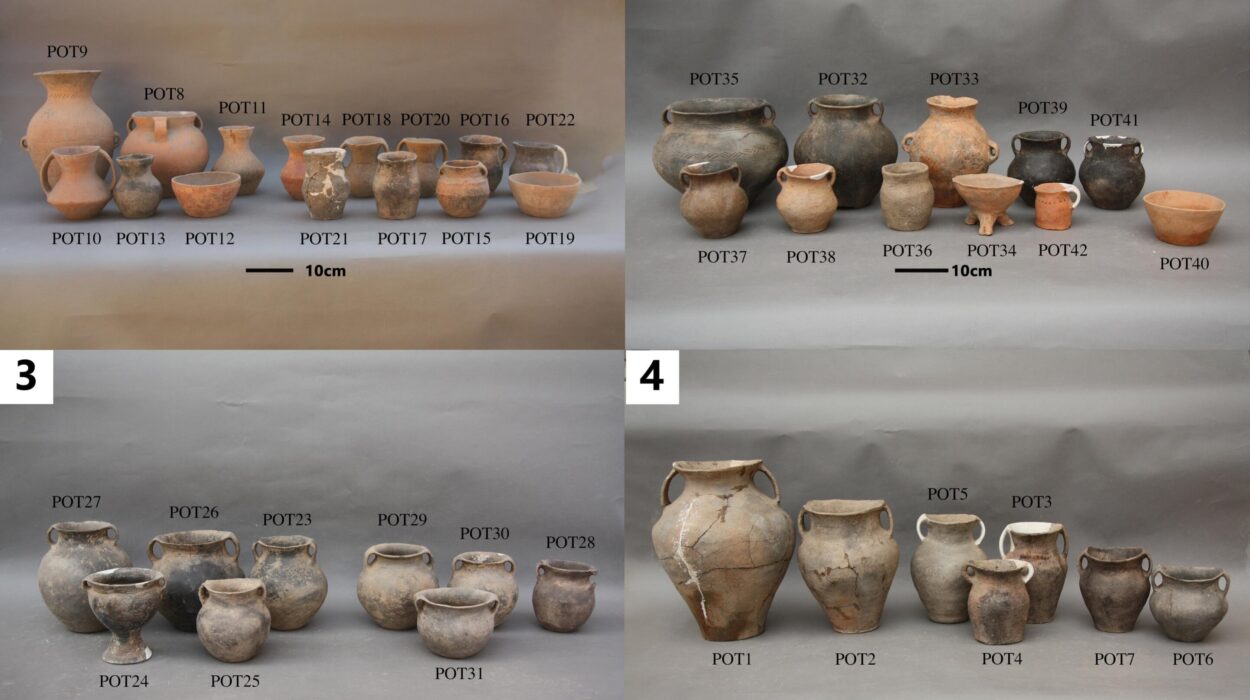

The bodies, seven in total, were recovered from two water wells at the ancient site of Mursa. They were all robust adult males between 18 and 50 years old—prime fighting age for Roman soldiers. Radiocarbon dating confirmed their burial during the second half of the 3rd century, aligning perfectly with the crisis years. A Roman coin, a sestertius minted in 251 CE, was found among the remains, serving as both an anchor in time and a chilling memento of their world.

Evidence of Battle and Brutality

The skeletal remains told a grim story. Several of the men bore injuries inflicted in life and in death—fractures to ribs and skulls, blunt force trauma, and sharp puncture wounds consistent with spears or swords.

Some of the wounds showed signs of healing, suggesting that these soldiers were veterans, accustomed to violence and survival. Others bore perimortem injuries—blows delivered just before or at the time of death. These men likely fell in battle, perhaps during or after the fateful confrontation known as the Battle of Mursa.

The researchers found no evidence of careful burial. The bodies appeared hastily disposed of, perhaps thrown into the wells in the aftermath of combat. There were no grave goods or rituals, only bones, mud, and a silence that endured for centuries.

The DNA of an Empire

The most surprising revelation came not from the bones themselves but from the DNA within them. Genomic analyses performed at the University of Tübingen in Germany uncovered a striking fact: none of these men shared ancestry with the local Iron Age populations of the region.

Their genetic signatures were astonishingly diverse, pointing to origins scattered across the vast expanse of the Roman world. Some traces linked to the eastern provinces, others to western Europe or the Mediterranean. This diversity painted a vivid picture of the Roman military at the time—a melting pot of cultures, languages, and ancestries.

The Roman army was not an army of Romans alone. By the 3rd century, the Empire routinely recruited soldiers from conquered territories and frontier regions. Men from distant lands fought side by side under the Roman banner, united by duty, pay, or survival rather than birthplace.

As the researchers wrote, “The observed genetic diversity might reflect the reliance of the Roman Empire on heterogeneous military recruitments, corroborating historical evidence for the integration of ‘foreign’ groups into imperial forces.”

The Men Who Fought and Fell

While their names are lost to history, the bones of these seven men whisper stories of loyalty and displacement. They were likely part of a garrison or a legion drawn from across the Empire—perhaps recruited from Gaul, Thrace, Syria, or North Africa.

In life, they might have spoken different tongues, eaten different foods, and worshipped different gods. Yet on the battlefield, they stood as one under the imperial eagle, defending a crumbling empire from enemies within and without.

Their final resting place—discarded in water wells—suggests the chaos that followed their deaths. Perhaps their comrades were forced to retreat, leaving the dead behind. Or perhaps they were the defeated, stripped of honor and abandoned by the victors.

Parallels Across Time

The discovery at Mursa echoes other historical mass graves where diverse armies met their end. Similar genetic diversity has been identified in burial sites of Napoleon’s Grand Army and in mass graves near Skopje. In each case, the graves tell a story not just of death, but of global human movement—of armies formed from many peoples, fighting for causes greater than themselves.

The Mursa soldiers embody that same theme. They were men caught in the machinery of empire, serving in distant lands far from home. Their bones testify to a universal truth of history: that war binds and breaks humanity in equal measure.

Science Revives Forgotten Lives

What makes this discovery extraordinary is not only what it tells us about the past but how it tells it. The Mursa investigation is a triumph of multidisciplinary science—archaeology revealing the physical evidence, genomics exposing ancestry, and isotopic analysis uncovering diet and migration.

By blending these tools, scientists can now resurrect human stories long thought lost. Every bone becomes a data point, every gene a clue to ancient lives. Together, they paint a vivid image of soldiers once flesh and blood—men who lived, fought, and died nearly two millennia ago.

The Broader Picture: Rome’s Human Tapestry

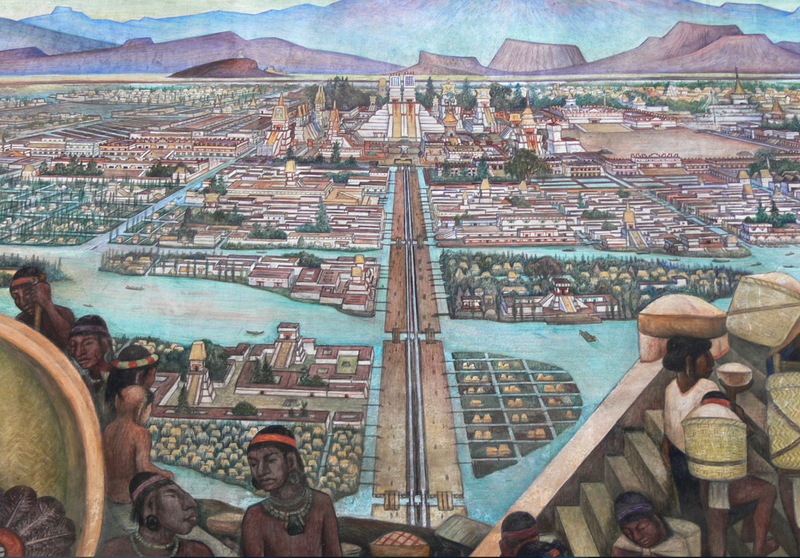

This discovery reinforces what historians have long suspected: that the Roman Empire was not merely a political or military system—it was a vast web of cultural exchange and human mobility.

From Britain to Mesopotamia, Rome’s power depended on the movement of people—soldiers, traders, slaves, and settlers. The army, in particular, was a reflection of this diversity. Recruits from conquered provinces gained citizenship, learned Latin, and adopted Roman customs, yet they also brought their own traditions and identities into the empire’s heart.

The soldiers of Mursa, in their diversity, exemplify this fusion. They were living symbols of Rome’s reach and its fragility. When the empire fractured, it was men like them who bore the brunt of its decline.

Remembering the Fallen of Mursa

For nearly 1,800 years, the soldiers of Mursa lay forgotten beneath layers of earth and history. Today, their rediscovery connects the present to a moment of chaos and courage in the ancient world.

They remind us that history is not only written in chronicles and monuments but buried in the soil beneath our feet. Each excavation is an act of remembrance—an acknowledgment of lives lived and lost.

In studying them, we are reminded that even in an age of empire and war, the essence of humanity endures: the will to survive, the bonds of comradeship, and the universality of sacrifice.

The Continuing Search for Answers

Archaeologists are continuing their work at Mursa, examining additional burial sites in hopes of understanding whether similar graves contain men of homogeneous or equally diverse ancestry. Each new discovery adds another layer to the complex story of the Roman frontier and its people.

The research stands as a testament to what collaboration between disciplines—and between nations—can achieve. It bridges the ancient and modern worlds, connecting the living with the dead through science and shared curiosity.

More information: Mario Novak et al, Multidisciplinary study of human remains from the 3rd century mass grave in the Roman city of Mursa, Croatia, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0333440