When Plato first spoke of Atlantis more than two thousand years ago, he wasn’t telling a bedtime story. Or at least, that’s what many believe. In two of his most famous dialogues—Timaeus and Critias—he described a vast and technologically advanced island nation that had supposedly existed some 9,000 years before his own time. Atlantis was powerful, majestic, and deeply flawed. In Plato’s account, its military ambitions led it to wage war on the rest of the known world, only to be struck down by divine retribution. In a single day and night, he claimed, Atlantis sank into the sea and vanished.

Plato’s tale was meant as a parable—a moral lesson about hubris and the dangers of imperial overreach. But he rooted it in real geography, naming its location as beyond the “Pillars of Heracles,” what we now know as the Strait of Gibraltar. That detail, along with his rich description of Atlantis’ culture, infrastructure, and sudden demise, has fueled more than two millennia of speculation.

Was Atlantis merely allegory, a philosopher’s way of exploring virtue and vice? Or was it a memory, distorted by time, of a real civilization lost beneath the waves?

A World Hungry for Lost Civilizations

The idea of a lost city buried by the sea has a hypnotic pull. Atlantis isn’t just a location—it’s a symbol. A reflection of our collective fear and fascination with cataclysm, of what we might lose and how quickly we might lose it. That emotional resonance explains why the Atlantis myth has never died.

Throughout history, the legend has been resurrected again and again—sometimes by scholars, more often by adventurers, mystics, and opportunists. It re-emerged during the Renaissance when ancient texts regained prestige and people searched for ancient wisdom. It surged again in the 19th century with the explosion of colonial exploration and pseudoscience, often laced with racial theories and nationalism.

In the modern era, Atlantis has appeared in novels, comic books, cartoons, and even conspiracy theories about alien civilizations and underwater pyramids. But beneath the layers of imagination and fantasy lies a compelling question: could the story have a core of historical truth?

Plato’s Atlantis: Fantasy or Distorted Memory?

To understand whether Atlantis could have been real, we must return to Plato. His dialogues describe an island empire larger than Libya and Asia Minor combined. It was divided into concentric circles of land and water, built with advanced engineering and full of wealth, including precious metals like orichalcum. Atlantis was blessed with a fertile climate, teeming forests, and a powerful navy.

But Plato’s goal wasn’t to write history. He was constructing a philosophical narrative. In Critias, the dialogue abruptly ends mid-sentence, and many scholars believe the story was unfinished—possibly even abandoned. There is no other contemporary Greek record of Atlantis before Plato. Not a single mention in Homer, Herodotus, or Thucydides.

Still, some believe Plato may have been drawing from older traditions—oral histories passed down from the Minoans, Egyptians, or perhaps even memories of natural disasters handed down through generations. Plato claimed that his source was Solon, the Athenian statesman who had visited Egypt and heard the tale from priests in the city of Sais. According to them, Atlantis existed 9,000 years before Solon’s time—far earlier than any known civilization.

That enormous timespan casts doubt on the story’s accuracy. Yet if one removes the exact numbers and looks instead at the pattern—the rise of a powerful island culture, its clash with other societies, and its sudden destruction—the echoes become harder to ignore.

The Minoans: A Civilization That Vanished

If there’s a real-world counterpart to Atlantis, it may be found in the ancient Minoan civilization.

Centered on the island of Crete, the Minoans flourished from around 2700 BCE to 1450 BCE. They were skilled sailors, engineers, and artists. Their palaces were elaborate, often multi-storied with plumbing systems and colorful frescoes that depicted rituals, animals, and mythic scenes. Their wealth, drawn from trade across the Mediterranean, was immense.

And then they disappeared.

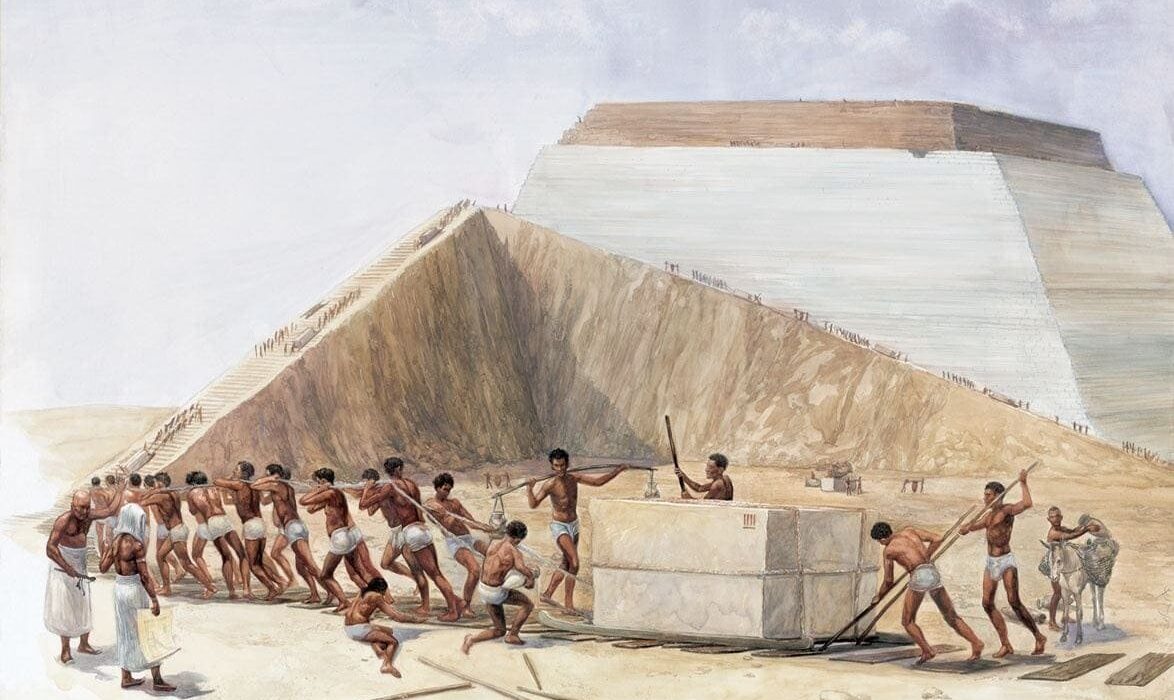

Not entirely, of course. But their dominance ended abruptly. One of the most widely accepted explanations is the eruption of Thera (modern-day Santorini) around 1600 BCE—one of the most violent volcanic events in recorded history. The eruption sent tsunamis sweeping across the Aegean, possibly decimating Minoan ports and infrastructure. Ash clouds may have choked crops and blackened skies for months. Some suggest this catastrophe made them vulnerable to Mycenaean conquest.

The similarities are tantalizing: a powerful maritime culture, located on an island, technologically advanced, undone by a natural disaster. Could this be the seed of the Atlantis story?

Many scholars think so. While the Minoans never matched the vast scale described by Plato, it’s possible that over centuries, oral retellings warped real history into myth.

Thera’s Explosion and Global Memory

The eruption at Thera was not a local event. Its effects rippled outward, altering the climate and possibly even affecting the Nile’s flood cycle. Modern geological evidence shows that the explosion ejected more than 60 cubic kilometers of rock and ash into the atmosphere—comparable to the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883 or Tambora in 1815.

Ancient cultures may have witnessed the skies darken and the seas roar. Some scholars speculate that memories of this apocalyptic event became embedded in myths—Atlantis in Greece, Deucalion’s flood, or even the biblical story of Noah.

Geologists drilling deep under the Mediterranean seabed have found evidence of tsunamis dating to the Bronze Age, consistent with the Thera eruption. A real disaster occurred. Whether it inspired Plato, directly or through layers of retelling, is a matter of interpretation.

Searching the Seafloor

Modern technology has reignited the hunt for Atlantis with sonar scans, deep-sea dives, and satellite imaging. Some searches have focused near the Azores, a volcanic archipelago in the Atlantic. Others have looked off the coast of Spain, around Cadiz and the Doñana National Park. In 2011, a team led by Richard Freund announced that they believed Atlantis had been buried in the mud flats of southern Spain by tsunamis. Their evidence included what appeared to be city-like shapes and circular patterns visible from satellite imagery.

Critics quickly dismissed the claims as speculative. The structures, many argued, were natural formations or Roman-era ruins. The scientific community remains deeply skeptical of “Atlantis sightings,” often citing a lack of peer-reviewed studies and archaeological rigor.

Nonetheless, the idea persists. Every few years, headlines announce a new discovery. In truth, much of the Earth’s ocean floor remains unmapped. Entire civilizations—if they existed—could still lie buried beneath layers of sediment and sea.

The Allure of Pseudoscience

Atlantis has not only attracted historians and archaeologists but also a host of fringe theorists. In the early 20th century, mystic Edgar Cayce claimed to channel Atlantean knowledge. He described Atlantis as a highly advanced culture powered by crystals and destroyed by misuse of energy.

Later, books like Chariots of the Gods? by Erich von Däniken speculated that Atlantis was a colony of extraterrestrials. Some claimed the Bermuda Triangle held the ruins. Others placed Atlantis in Antarctica, India, or even the Caribbean.

These theories—while colorful—lack credible evidence. They often cherry-pick data, ignore contrary findings, or reinterpret myths to fit preconceived conclusions. Yet they remain popular, in part because they tap into something deeper: a longing for forgotten wisdom, for mystery, for meaning.

In a world that often feels too mapped, too known, Atlantis offers a mythic frontier.

Lost Worlds in the Real Record

There is no need to invent Atlantis to find wonder. Archaeology has uncovered dozens of lost cities—real, not mythical—once buried by sands, jungles, or water.

The city of Dwarka in India, once considered purely mythological, was found submerged off the coast of Gujarat, revealing temple ruins and artifacts. Pavlopetri in Greece, an underwater Bronze Age city, preserves roads, buildings, and tombs more than 5,000 years old.

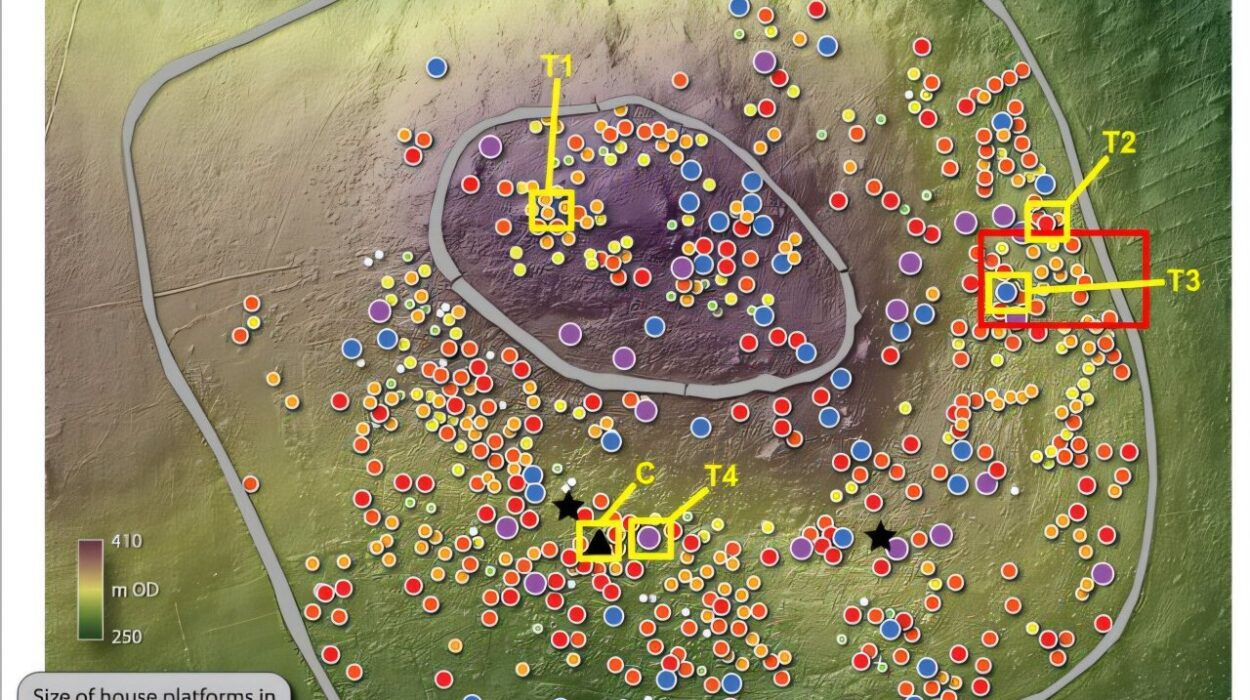

In the Americas, sites like Cahokia or the Amazon’s geoglyphs suggest complex societies that vanished before European contact. In Turkey, Göbekli Tepe challenged assumptions by revealing monumental structures built by pre-agricultural peoples over 11,000 years ago.

The Earth hides its history well. With every year, technology gives us better tools to uncover it.

Atlantis as a Mirror

Whether or not Atlantis was real, it serves a profound purpose.

Plato used it to explore the fallibility of civilization. He warned that even the most enlightened society could collapse under the weight of its own ambition. Today, the legend serves a different function—it reflects our fears and desires, our sense of loss, and our hope that there is still magic in the world.

The story asks us to look deeper—beneath the waves, beneath the myths, beneath our assumptions. It challenges us to imagine civilizations not yet discovered, and perhaps to think more carefully about how we preserve our own.

Conclusion: Between Myth and Memory

Science has not found Atlantis. But it has revealed the power of volcanic eruptions to erase whole cultures. It has shown us that the ocean, while vast, can swallow empires. It has also reminded us that myths often have roots in reality—blurred, shifted, but not entirely invented.

Atlantis may never be proven. It may remain forever on the edge of the map, marked not by coordinates but by imagination.

Yet the search continues—not just for a city beneath the sea, but for something older and deeper: a story that connects us, a mystery that reminds us of what lies hidden in the deep, and a warning of what we might lose if we forget to listen to the echoes of the past.