For generations, our understanding of human history relied on what our ancestors left behind—bones, tools, paintings on cave walls, the charred remains of ancient hearths. Archaeologists sifted through soil, piecing together stories of migration, conflict, and culture. But these stories, as detailed and insightful as they were, always had missing pieces. The past was a puzzle with many of its most vital parts lost to time.

Then something extraordinary happened. In the 1980s, researchers began isolating ancient DNA—genetic material preserved in the remains of people who lived tens of thousands of years ago. At first, it was crude and unreliable. The technology to read and interpret degraded DNA sequences barely existed. But like a whisper from the past growing steadily louder, ancient DNA became one of the most powerful tools ever discovered in the study of human origins.

What followed was a revolution—not just in archaeology or biology, but in how we understand ourselves as a species.

Cracking the Genetic Time Capsule

DNA is a fragile molecule. It decays rapidly when exposed to heat, humidity, and time. The dream of extracting useful genetic information from ancient human remains seemed laughable in the early days. But scientists persevered. They began looking in the coldest places—the Arctic, high-altitude caves, permafrost—and discovered that under the right conditions, fragments of DNA could survive for tens of thousands of years.

Then came the rise of next-generation sequencing: machines capable of reading millions of DNA fragments at once. Suddenly, the scraps of degraded ancient genomes could be reassembled like a mosaic. We weren’t just guessing anymore—we were listening directly to the voices of our ancestors, encoded in their biology.

In 2010, the genome of a Neanderthal was published for the first time. Months later, another ancient human was sequenced—this one from a previously unknown group that had never been identified by archaeologists. They were dubbed the Denisovans, named after the Siberian cave where their tiny finger bone had been found. It was a stunning discovery: proof that the human family tree had more branches than we had ever imagined.

Neanderthals, Denisovans, and the Ghosts in Our Genes

For much of the 20th century, the story of Homo sapiens was told as a triumph of progress. We evolved in Africa, spread across the globe, and outcompeted all rivals—including the brutish Neanderthals who vanished around 40,000 years ago. But ancient DNA has upended that narrative.

We now know that modern humans didn’t simply replace other human species—they interbred with them.

Today, nearly all non-African people carry 1–2% Neanderthal DNA. In some populations, especially in Oceania, there’s an additional dose of Denisovan DNA, up to 5%. These traces are not just footnotes—they affect immune systems, fat storage, even skin color and how our bodies respond to altitude.

Our ancestors weren’t isolated branches. They were tangled vines, weaving and reweaving across time. Human evolution was not a neat procession but a swirling mosaic of encounters, mingling, and hybrid vigor.

Rewriting the Story of Human Migration

For decades, the prevailing theory held that Homo sapiens left Africa around 60,000 years ago and slowly populated the rest of the world. But ancient DNA has complicated that timeline dramatically.

It turns out that there were earlier migrations—perhaps as far back as 120,000 years ago. These early explorers didn’t leave lasting genetic legacies, but their journeys are being rediscovered through archaeology and genetics alike.

Even more surprising has been the realization that human populations have undergone vast turnovers. In Europe, for instance, ancient DNA shows that the people who built the megaliths—Stonehenge among them—were almost entirely replaced by newcomers from the steppes of what is now Russia and Ukraine around 4,500 years ago. These newcomers, linked to the Yamnaya culture, brought new technologies, languages, and genetics that would reshape Europe forever.

Similar upheavals occurred in South Asia, where the ancient Indus Valley Civilization gave way to populations carrying steppe ancestry, and in sub-Saharan Africa, where Bantu-speaking peoples spread across the continent, replacing and mixing with older groups.

Human history, once seen as the slow accumulation of change, now looks more like a series of sudden transformations—driven by migration, conquest, collapse, and rebirth.

The Ancient Africans Speak

For too long, Africa—the cradle of humanity—was left out of genetic research. DNA degrades quickly in warm climates, and the lack of ancient genomes from the continent left a yawning gap in our understanding. That is beginning to change.

Recent studies have revealed that African genetic history is astonishingly complex. Far from being a monolithic origin point, ancient Africa was home to a multitude of diverse and deeply diverged human populations—many of which no longer exist.

Some ancient African individuals show no close connection to any living group. Others are closer to hunter-gatherers in the south, or to pastoralists in the east. The data suggest that early Homo sapiens weren’t a single population but a network of interacting groups spread across the continent, mixing and diverging over hundreds of thousands of years.

Even more tantalizing are the signs of so-called “ghost lineages”—extinct human populations that left no bones behind but whose DNA survives in modern Africans. These unknown ancestors may have split from the Homo sapiens line as far back as 500,000 years ago, only to later rejoin the human gene pool through interbreeding.

Africa’s genetic legacy is not just deep—it is vast, layered, and far from fully mapped. Each new ancient genome from the continent peels back another layer of forgotten prehistory.

The Americas: A Tale of Ice, Isolation, and Surprise

The peopling of the Americas has long been one of archaeology’s great debates. Who were the first Americans? When did they arrive? And how?

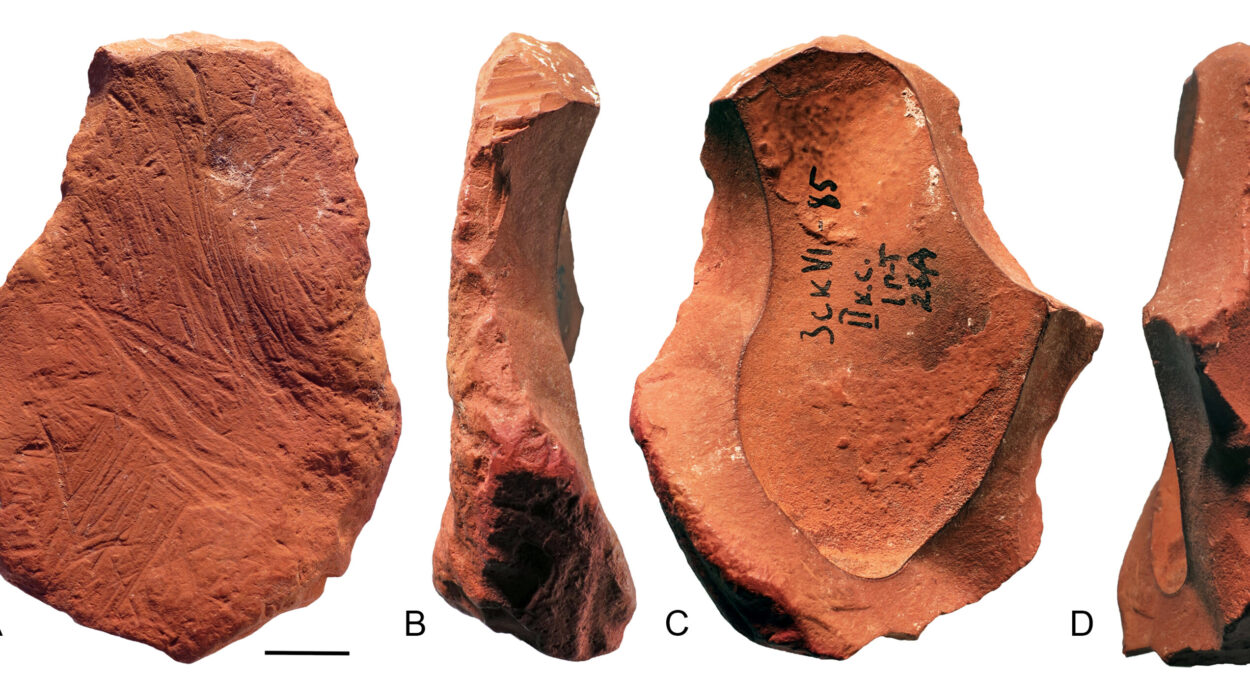

For years, the Clovis culture—known for distinctive stone tools—was thought to represent the earliest settlers, arriving around 13,000 years ago. But ancient DNA has pushed that date back even further. Remains from Montana, Alaska, and even central Brazil reveal a much older and more diverse picture.

Genetic data now suggest that the first humans arrived in the Americas at least 15,000 years ago—possibly earlier—via a coastal route along the Pacific or a now-submerged land bridge through Beringia. These early migrants split into multiple groups, some moving south quickly, others staying in the north.

Even more stunning was the discovery of ancient Brazilian remains with genetic affinities to modern Indigenous Australians and Melanesians. Though still hotly debated, it suggests that early humans may have made their way into the Americas in multiple waves from different regions—not just northeast Asia.

In South America, DNA has revealed rapid movement across vast distances. Some lineages vanished entirely, replaced by later arrivals. The genetic record tells a story of expansion, extinction, and survival that spans thousands of years and countless generations.

The Unexpected Impact of Epidemics and Empires

History books tell us about empires and conquests. Ancient DNA shows us their true cost.

When the Romans expanded across Europe, they brought not just roads and laws, but also diseases and genetic shifts. When Genghis Khan’s armies thundered across Asia, they didn’t just reshape borders—they left traces in the genomes of millions.

In the Americas, the most devastating impact of colonization wasn’t recorded by scribes but in the genes of survivors. Ancient DNA shows a massive population collapse following European contact—up to 90% in some regions—due to disease, war, and displacement. Entire genetic lineages vanished.

But resilience also shines through. In many Indigenous communities, ancient genomes have helped people reconnect with lost histories, languages, and ancestral lands. The genetic past is not just a story of erasure—it is also a story of endurance.

Ethics, Identity, and the Power of the Past

The ability to sequence ancient DNA is a scientific miracle—but it comes with profound ethical questions.

Who owns the DNA of the dead? Should researchers study remains without the permission of descendant communities? What happens when genetic data contradict oral histories or cultural identities?

In recent years, Indigenous groups around the world have demanded more say in how ancient DNA is used. Some have embraced it as a way to validate traditions. Others see it as a violation of the sacred.

In the United States, the remains of a 9,000-year-old man found in Washington State sparked a decades-long legal battle. Scientists wanted to study his bones; Native American tribes wanted to bury him. Eventually, ancient DNA proved he was closely related to modern tribes, who reburied him with ceremony and honor.

Science, for all its power, must tread carefully. The stories encoded in ancient DNA are not just data points. They are the memories of human beings—our ancestors—and deserve respect.

A Revolution Still Unfolding

We are only at the beginning of the ancient DNA revolution. Every month brings new discoveries: a 7,000-year-old mummy in Egypt that challenges ideas about early farming; a teenage girl in Indonesia who belonged to a previously unknown lineage; a burial site in Sweden revealing surprising genetic links to distant Siberia.

The world of our ancestors was richer, more interconnected, and more surprising than we ever imagined. Ancient DNA is not just changing the timeline—it is changing the entire map.

It tells us that human history is not a straight road, but a braided river. That our species was never alone. That our differences are recent, and our connections run deep.

The genes that shape our eyes and skin are only the surface. Beneath them lies a shared inheritance, passed down not just from kings and conquerors, but from hunters, midwives, potters, and storytellers—the countless ordinary people whose lives shaped the world we live in.

What the Future Holds

As technology advances, the next frontier is even more breathtaking. Scientists are developing ways to read DNA from dirt, bones, even the air. Soon, we may be able to reconstruct entire communities—not just who lived there, but what they ate, what diseases they had, what they feared and believed.

We may one day piece together the full genome of our deepest ancestors—not just Neanderthals and Denisovans, but Homo erectus, Homo floresiensis, and perhaps others not yet discovered. We may learn how language emerged, how culture spread, and even how our minds came to be.

The science of ancient DNA is not just rewriting history. It is revealing that history itself is more fluid, more human, and more miraculous than we ever dared to believe.