In the sun-scorched hills of southeastern Turkey, near the city of Şanlıurfa, a grassy mound slumbered for thousands of years beneath layers of windblown soil and the silence of forgotten time. The locals called it Göbekli Tepe—Potbelly Hill. To farmers, it was just a gentle rise in the land. They plowed it, grazed animals atop it, and occasionally unearthed strange stones that no one could explain. For generations, no one imagined that the world’s oldest known temple complex lay hidden just below the surface.

It wasn’t until 1994, when German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt visited the site, that the story of Göbekli Tepe began to reemerge from oblivion. Schmidt was not the first archaeologist to walk the hill, but he was the first to recognize that the carved stone fragments scattered around were not remnants of a medieval cemetery, as previously believed, but part of a prehistoric monument. And not just any monument—this was something that would rewrite the very timeline of civilization.

Beneath that mound lay something older than any cathedral, older than the pyramids, older even than agriculture itself. With radiocarbon dating placing its construction at around 9600 BCE, Göbekli Tepe predates Stonehenge by more than 6,000 years. It was a place of ritual, spirituality, and mystery—built not by farmers or kings, but by bands of hunter-gatherers before the invention of writing, pottery, or the wheel.

What they built would turn history on its head.

A Puzzle That Defies the Timeline

Before Göbekli Tepe, archaeologists believed that large-scale architecture only arose after the development of farming. The narrative was simple and widely accepted: first, humans discovered agriculture. Then, surplus food allowed people to settle in one place, form societies, create governments, develop religion, and finally, build monumental structures. Civilization, it was believed, began with the plow.

But the stones of Göbekli Tepe say otherwise.

With dozens of circular enclosures containing massive T-shaped pillars—some towering over 16 feet high and weighing up to 20 tons—the site demonstrates advanced planning, engineering, and artistic vision. These stones are decorated with meticulously carved reliefs: fierce predators like lions and snakes, soaring birds, crawling insects, and stylized human-like figures with bent arms and abstract faces. There are no signs of agriculture at the site. No domesticated plants. No ceramic pots. No permanent houses.

This sacred place was not surrounded by a city. Instead, it was likely a gathering place for groups from surrounding regions, possibly for seasonal rituals or festivals. The people who built Göbekli Tepe lived as mobile foragers, yet came together in organized numbers to construct something so grand and complex that it challenges all assumptions about what prehistoric societies were capable of.

The implications are enormous. If hunter-gatherers could organize, collaborate, and create such a place, then perhaps the roots of civilization lie not in farming, but in the spiritual, communal, and symbolic worlds of early humans.

The Monumental Mystery

What exactly was Göbekli Tepe used for? That question remains a subject of heated debate. The lack of domestic structures and tools for everyday life suggests it wasn’t a village or a place where people lived year-round. Instead, the layout, scale, and iconography point strongly to religious or ceremonial use.

The enclosures—most famously Enclosure D—feature two central T-shaped pillars surrounded by rings of similar stones. These central pillars, with stylized arms and hands, appear anthropomorphic. They may represent deities, ancestors, or mythical figures. The surrounding stones, carved with animals, may symbolize elements of myth, seasonal cycles, totemic identities, or cosmological beliefs.

Scholars have proposed that Göbekli Tepe was a place of ritual death and rebirth, a site where the human relationship with nature and the cosmos was enacted in stone. The vulture imagery in particular echoes burial rites from other sites in the region, where bodies were exposed to carrion birds as part of sky burials. This has led to the theory that Göbekli Tepe was connected to death rituals and ancestor worship.

Others suggest it served as a neutral ground where scattered groups gathered for social bonding, intermarriage, and the exchange of goods and ideas. These gatherings may have included feasting, music, storytelling, and ceremonies that reinforced a shared cultural identity.

Whatever the precise function, the site reveals an extraordinary level of symbolic thinking and spiritual consciousness in early humans—far earlier than anyone previously believed.

Engineering Without Tools

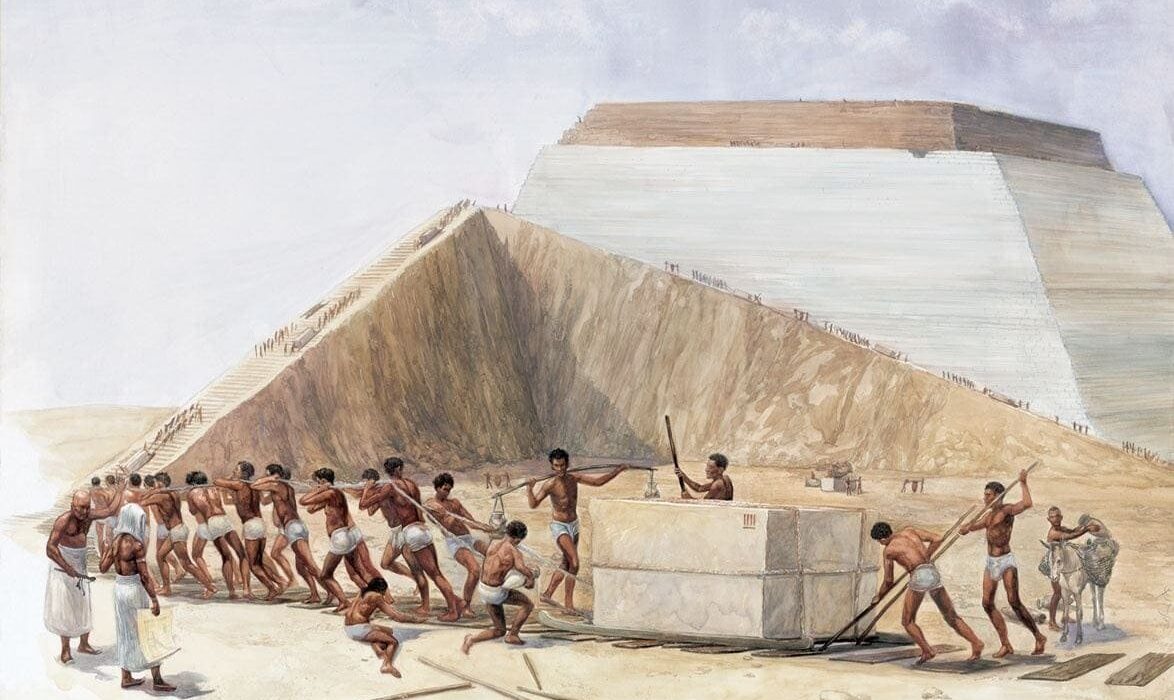

Perhaps the most astonishing aspect of Göbekli Tepe is its construction. Without metal tools, wheels, or domesticated animals, its builders cut and moved massive stone pillars—some weighing over 20 tons—from nearby quarries to the site. They dug deep foundation pits, erected the stones upright, and fitted them into complex architectural arrangements.

How did they do it?

The answer remains speculative. Most scholars believe the stones were carved using stone tools such as flint picks and hammerstones. Transportation likely involved dragging the stones on sledges over log rollers or prepared tracks. Ropes made from plant fibers could have been used to pull and position the pillars. The labor required to quarry, carve, transport, and erect these stones suggests a high degree of social coordination and possibly the existence of skilled workers and leaders.

This implies an emerging social hierarchy or at least specialized roles within the community—another blow to the outdated image of Paleolithic humans as simple bands of nomadic survivalists.

Göbekli Tepe may mark one of the first moments in history when large-scale human cooperation became formalized, perhaps even institutionalized. It is a monument not just to spiritual beliefs, but to the growing complexity of social life.

The Temple Before the Farm?

Göbekli Tepe challenges the fundamental sequence of civilization: what if religion—not agriculture—came first?

It has long been assumed that permanent settlements arose only after humans began farming. But Göbekli Tepe suggests the opposite. People may have first gathered for religious or communal reasons, and only later adopted farming as a means to support such gatherings.

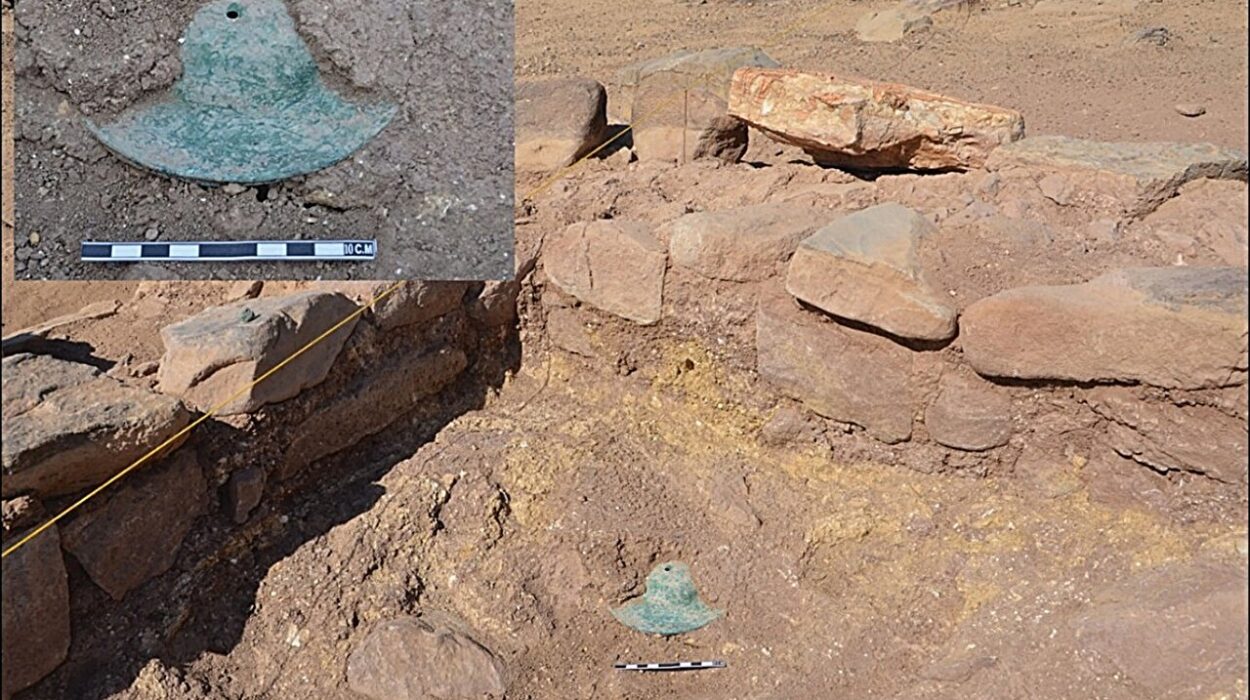

Recent excavations near the site have revealed the earliest evidence of domesticated einkorn wheat—an ancestor of modern wheat—just a few miles from Göbekli Tepe. This has led to the provocative theory that the construction of the site created a demand for food that eventually led to the cultivation of grains. In other words, the need to feed workers and pilgrims may have inspired the agricultural revolution.

If true, this overturns the most deeply ingrained assumptions about how civilization began. The human impulse to build sacred places and share symbolic experiences may have been the very force that pulled our ancestors out of the forests and into the fields.

Göbekli Tepe thus becomes the cornerstone of a new origin story: one in which culture drives economy, not the other way around.

A Network of Forgotten Sites

For decades, Göbekli Tepe stood alone as a prehistoric enigma. But now, other sites are emerging that suggest it was not unique, but part of a much larger cultural phenomenon. Excavations at Karahan Tepe, about 35 kilometers from Göbekli Tepe, have uncovered similar megalithic structures, including T-shaped pillars and sculpted figures. Dubbed “Göbekli Tepe’s sister site,” Karahan Tepe dates to the same era and may be even older in some parts.

Together with smaller sites like Nevali Çori and Sefer Tepe, these locations form what some researchers now call the “Taş Tepeler” (Stone Hills) cultural complex—an interconnected network of early monumental centers that flourished in southeastern Anatolia during the 10th millennium BCE.

This suggests that Göbekli Tepe was not an isolated marvel, but part of a broad and sophisticated tradition that spanned generations and regions. These sites point to a dense, ritual-rich society, one with shared architectural styles, iconography, and belief systems.

The scale of this culture—and the relative lack of attention it has received until recently—hints at how much of prehistory remains buried, unrecognized and misunderstood. It’s entirely possible that more Göbekli Tepes lie waiting under hills and fields across the Fertile Crescent, each with its own secrets to share.

Myth, Memory, and Meaning

The power of Göbekli Tepe lies not only in its stones, but in what it reveals about the human spirit. For the first time in history, we see humans as visionaries—not just survivors. We see them not simply as creatures reacting to their environment, but as beings shaping it with imagination, belief, and symbolic power.

These people weren’t nameless, faceless primitives. They were artists, architects, astronomers, and shamans. They looked to the stars, worshipped their dead, and carved their fears and dreams into limestone. Their work reminds us that religion, myth, and meaning were not byproducts of civilization—they were its foundation.

The animals carved into the stones—leopards, vultures, scorpions, foxes—may have carried mythological meaning, perhaps as totems or protectors. Some researchers have speculated that the arrangement of certain enclosures may reflect astronomical alignments, suggesting that the builders tracked celestial events like solstices or the rising of key stars.

Whether these theories prove true or not, they underscore a critical point: the people of Göbekli Tepe were observing, reflecting, and creating. They were not just surviving—they were building a worldview.

Buried by Intention

Perhaps the greatest mystery of Göbekli Tepe is not why it was built, but why it was buried.

Each of the monumental enclosures was filled in with rubble and refuse—animal bones, stone tools, and broken fragments—carefully packed in. This was not the work of time or nature; it was intentional. The builders themselves covered the site, preserving it beneath a protective layer that kept the stones safe for over 10,000 years.

Why?

Some suggest the site was decommissioned, perhaps as beliefs changed or communities moved. Others believe it was a ritual burial—a symbolic act of closing a chapter in the human journey. Or perhaps the landscape itself became sacred, and burying the stones returned them to the earth they had risen from.

Whatever the reason, the act of burial ensured that Göbekli Tepe would not disappear entirely. It waited, silent and untouched, for the day its story could be told again.

Excavation and Controversy

Though excavation has been ongoing for decades, only a small portion of Göbekli Tepe has been uncovered—perhaps as little as 5 to 10 percent. What lies beneath the rest of the mound remains unknown, protected by both the soil and a growing awareness of the need for careful, methodical research.

The Turkish government has invested heavily in the site, building a museum in Şanlıurfa and promoting the region as a center for archaeological tourism. In 2018, Göbekli Tepe was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Interest from around the world has surged.

Yet the site is not without controversy. Some scholars worry that rapid development and tourism could damage the fragile context of the remaining enclosures. Others caution against wild theories that link the site to Atlantis, aliens, or lost super-civilizations—claims not supported by evidence, but popularized in media and fringe literature.

The real story of Göbekli Tepe is already astonishing. It needs no embellishment. It is the story of early humans at their most inspired and enigmatic—a story still being written by archaeologists and researchers each year.

Rethinking Human History

Göbekli Tepe is more than a site—it’s a mirror, reflecting a version of humanity that we have only just begun to understand. It challenges us to rethink the narrative of progress, to reconsider what it means to be civilized.

It reminds us that long before cities and empires, there were visionaries who carved their beliefs into stone and gathered beneath the open sky to share something larger than themselves.

In that sense, Göbekli Tepe is not a mystery to solve, but a message to remember. It speaks to the roots of art, religion, cooperation, and imagination. And it whispers to us that perhaps the foundations of civilization were always spiritual before they were practical—carved not only in limestone, but in the human heart.