Every culture tells stories—of creation, of gods, of floods and heroes, of lost cities and golden ages. Myths have long shaped the way civilizations understood their world, but for much of modern history, scientists and historians relegated them to the realm of fantasy. Myths were seen as metaphors at best, or the hallucinations of pre-scientific minds at worst.

But in recent decades, archaeology has begun to peer beneath the poetic veils of these ancient narratives—and what it finds is often astonishing. Sometimes, shreds of truth shimmer beneath the legends. Cities thought to be fictional emerge from the dust. Cataclysms once dismissed as imagination turn out to be etched in the geological record. And heroes once considered symbolic leave behind real-world footprints.

This dance between archaeology and myth is not about proving that every dragon or deity once walked the Earth. It’s about something deeper: understanding how human beings used storytelling to encode memory, trauma, history, and even survival.

Troy and the Wrath of Achilles

For centuries, the tale of Troy was a masterpiece of ancient Greek literature—and little more. Homer’s Iliad, with its gods and heroes, was celebrated for its artistry but dismissed as historical fiction. The idea that a real Trojan War had taken place was seen as romantic nonsense.

Then came Heinrich Schliemann.

A German businessman turned archaeologist, Schliemann followed Homer’s words not as poetry but as geographic clues. In the 1870s, he began digging in Hisarlik, a hill in modern-day Turkey. There, beneath layers of earth and time, he uncovered ruins of a massive city—one that had been destroyed and rebuilt many times. Among the layers was evidence of a city burned and besieged in the 12th or 13th century BCE.

Could this have been the real Troy?

Modern archaeologists now largely agree that Hisarlik is indeed the site of ancient Troy. While the Iliad may not recount events exactly as they happened, the story likely draws from a real conflict—perhaps even several—that took place during the Late Bronze Age collapse.

Troy’s discovery ignited a revolution. If Homer’s song contained truth, how many other myths might echo reality?

Floods, Arks, and a Shattered Memory

Few stories are more widespread than that of a great flood. From the Epic of Gilgamesh in Mesopotamia to the Book of Genesis, from Hindu texts to Aboriginal legends, tales of a deluge wiping out civilization span continents and centuries.

Could they all be exaggerating the same ancient catastrophe?

In Mesopotamia, where the Tigris and Euphrates meet, archaeologists uncovered flood layers in ancient cities like Shuruppak and Ur—places linked to Sumerian flood myths. These floods were local but massive, capable of reshaping the landscape and terrifying survivors.

Further north, in the Black Sea region, marine geologists have found submerged shorelines suggesting a sudden and violent expansion of the sea around 5600 BCE. The theory, proposed by William Ryan and Walter Pitman in the 1990s, argues that melting glaciers caused the Mediterranean to burst into the freshwater lake of the Black Sea, flooding coastal settlements with ferocious speed.

While the theory remains debated, it raises profound possibilities. Could the memory of such a flood—passed down through oral tradition—have eventually become the biblical story of Noah or the Babylonian tale of Utnapishtim?

Here, geology and archaeology provide a bridge across millennia, suggesting that even the most epic myths may carry the weight of real human suffering.

The Lost City of the Monkey God

In the dense jungles of Honduras, rumors have long whispered of a city buried by time and vegetation. Indigenous tales spoke of a “White City,” or the “City of the Monkey God”—a place of beauty and curse, where gods walked and men vanished.

For decades, explorers searched for it. Most failed. Some disappeared. Skeptics labeled it legend.

Then, in 2012, high-tech LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) scans from aircraft flying over the Mosquitia jungle revealed geometric structures hidden beneath the canopy—evidence of pyramids, plazas, and canals. A ground expedition in 2015 confirmed the find: a previously unknown civilization had indeed built a vast city there, later reclaimed by nature.

The legend was not entirely mythic.

Archaeologists caution that the story of the “Monkey God” is not literally true, but the local oral traditions—told and retold for centuries—pointed toward a real place, a lost society once thriving in isolation.

This discovery underscores a vital truth: local mythologies often encode geographic memory. Where Western science dismissed them, indigenous wisdom remembered.

Atlantis: Sunken Dream or Misplaced History?

No tale captures the imagination quite like Atlantis. Plato’s ancient account describes an advanced civilization that vanished beneath the waves in a single day and night. For some, it’s allegory. For others, it’s obsession.

Atlantis has been “found” everywhere—from the Bahamas to Antarctica, from the Mediterranean to South America. Most claims crumble under scrutiny. Plato’s tale, after all, was meant as a philosophical warning against hubris, not a travelogue.

Yet recent archaeological work has added fuel to the speculation. In the Mediterranean, the eruption of Thera (modern-day Santorini) around 1600 BCE was one of the most violent volcanic events in history. It devastated the Minoan civilization, a sophisticated maritime culture centered on Crete.

The Minoans had art, plumbing, written language, and trade stretching across the Aegean. Then, quite suddenly, they vanished—or more accurately, were absorbed and displaced. The tsunami and climate disruption caused by the eruption might have inspired later tales of a vanished world.

Was Plato’s Atlantis a distorted memory of the Minoans? Did Greek travelers, centuries later, hear garbled echoes of a real catastrophe?

While we may never know for certain, the fusion of myth and archaeology in this case is tantalizingly close.

Giants in the Earth: Mythic Beings and Ancient Bones

Myths around the world are populated by giants. The Bible speaks of the Nephilim. Norse legends tell of frost giants. In Native American traditions, enormous beings often shape the land or war with humans.

For centuries, these stories were considered pure fantasy.

But then, archaeologists began unearthing the remains of megalithic cultures—people who moved massive stones to build burial sites, temples, and observatories. In places like Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, dating back to 9600 BCE, massive T-shaped pillars carved with animals and symbols challenge our assumptions about prehistoric humans.

The people who built these structures were not physically giant, but their accomplishments certainly were. Without metal tools or the wheel, they reshaped the Earth with monumental ambition.

In some cases, fossilized bones of extinct megafauna—like mammoths or giant ground sloths—may have inspired legends of giants. To an ancient observer, a femur as long as a man might easily belong to a race of titans.

While science does not confirm the existence of literal giants, it helps us understand how awe-inspiring discoveries of the past could become mythic tales passed down for thousands of years.

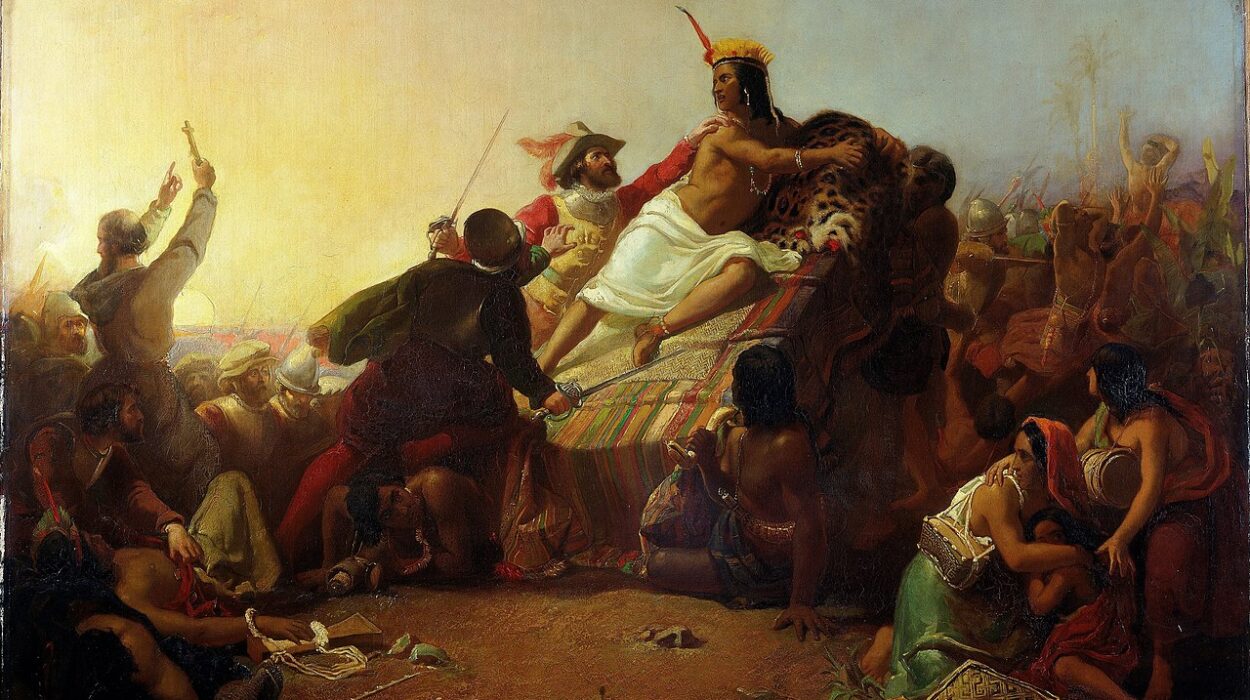

When Gods Walked Among Men

Ancient mythologies are filled with divine beings descending to Earth—Zeus and Odin, Shiva and Quetzalcoatl. Often, these deities taught skills, brought fire, or judged humanity. Skeptics dismiss them as personifications of natural forces or psychological archetypes.

But archaeology offers another lens.

In Central America, the Maya and Aztec civilizations told stories of gods who gave calendars, mathematics, and astronomy. Excavations of their temples reveal sophisticated knowledge of celestial cycles, solstices, and planetary movement—encoded in pyramids aligned with cosmic precision.

In Egypt, myths described Thoth, the god of writing and wisdom. The actual invention of writing in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt coincides with a flourishing of administrative and religious systems—an explosion of “godly” knowledge.

While archaeology doesn’t confirm gods as literal beings, it reveals how transformative innovations—like language, astronomy, or metallurgy—could be mythologized as gifts from higher powers.

The line between miracle and invention, especially in ancient times, is often razor-thin.

The Oracle and the Earthquake

Delphi, in ancient Greece, was said to be the navel of the world—a place where the god Apollo spoke through a priestess known as the Pythia. Her cryptic prophecies shaped politics, war, and culture. Skeptics long dismissed her visions as theatrics.

But geological studies in the late 20th century revealed that the temple sits atop a fault line. Natural gases—particularly ethylene, which can induce trance-like states—likely seeped through cracks in the floor. Inhaling these, the priestess may well have experienced altered states of consciousness, explaining the ecstatic rituals described in ancient texts.

Once again, science does not mock the myth—it illuminates it.

The Delphic Oracle becomes not a fraud, but a window into how ancient people engaged with the powerful forces of nature.

How Far Can Science Go?

Archaeology is not a tool for proving myths “true” or “false” in black-and-white terms. It works in strata, nuance, and probability. Myths are not scientific documents, but that doesn’t make them worthless. They are cultural time capsules, preserving ancient hopes, fears, and memories.

Yet science can now analyze soil for ancient pollen, scan underground structures with radar, date wood with precision, and reconstruct landscapes lost beneath oceans. As its tools grow sharper, archaeology becomes a decoder of stories—revealing when myth aligns with memory.

New techniques, like DNA analysis, are even shedding light on ancient family lines and migrations, sometimes validating tribal or cultural origin stories previously dismissed as fiction.

But science has limits. It cannot weigh the spiritual meaning of a myth. It cannot measure belief, or fully decode poetry. What it can do is help us understand the context, the conditions, the human spark behind the legend.

Why This Matters Now

In a world increasingly obsessed with data and evidence, myths remind us that truth is not always found in numbers. Myths teach values, convey identity, and offer wisdom that pure fact sometimes cannot.

Yet, when science and myth work together—when a legend inspires an expedition, and archaeology lends it shape—we get something extraordinary. We get to see through ancient eyes, walk lost roads, and feel the echo of ancestors reaching across time.

In this age of satellites and deep-earth scanners, it’s tempting to believe we’ve already discovered all there is to know. But the Earth is still full of secrets, and the human story is far from complete.

Maybe, just maybe, some of our wildest stories are still waiting to be uncovered, not disproven.

Conclusion: The Myth of the Myth

Myths are not lies. They are the soul’s way of remembering. Whether born from trauma, awe, or revelation, they encode how ancient people understood the world and their place in it. Archaeology, in its most poetic form, is not about digging up bones and stones—it’s about listening.

And if we listen closely, with science in one hand and wonder in the other, we might hear echoes not just of the past—but of the truth hidden within the tales.