Beneath our feet lies a forgotten world—one carved not by nature alone but by the chisels, hands, and fears of ancient civilizations. Across continents and centuries, people have tunneled into the earth to create elaborate underground cities: self-contained, mysterious, and often baffling even to modern science. These subterranean realms are not mere shelters or hiding spots. They are entire communities, complex in architecture and haunting in design.

Some of these cities are buried beneath deserts and volcanic plains. Others lie below bustling modern towns, hidden in plain sight. Many were lost to history, buried by time or intentionally sealed, only to be rediscovered centuries later with wonder and confusion. Their existence forces us to rethink the resilience, ingenuity, and perhaps even desperation of those who built them. Who were these people? What were they hiding from? And how did they accomplish such feats of engineering with tools we now deem primitive?

This is not a story of fantasy or myth, but of archaeology, geology, and the indomitable human will to survive—even if that meant vanishing from the surface of the Earth.

The Enigma of Derinkuyu

In the heart of Turkey’s Cappadocia region lies a labyrinthine marvel: Derinkuyu. It stretches some 60 meters below the surface and could once shelter more than 20,000 people. It was rediscovered not by an archaeologist, but by accident. In 1963, a man knocking down a wall in his basement stumbled upon a hidden passageway. That led to more corridors, rooms, wells, ventilation shafts—an entire city beneath the city.

Derinkuyu is the deepest of over 200 known underground settlements in the region. Its purpose was clear: protection. Cappadocia has long been a crossroads of empires and conflict. Christians fleeing Roman persecution, later Byzantine citizens evading Arab raiders, and perhaps even earlier civilizations all sought safety beneath the earth.

But what still puzzles researchers is the sheer scale and sophistication. The city had food storage rooms, wine presses, stables, schools, and chapels. Large circular stones were used as doors, rolled across entryways to seal off chambers from intruders. Complex air shafts provided ventilation, and there was even a water system that connected with underground springs—carefully designed so invaders couldn’t poison it from above.

To create such a structure would have required planning, geological knowledge, and a deep understanding of the volcanic rock known as tuff—a soft material that hardens when exposed to air, making it ideal for carving. The people of Derinkuyu weren’t merely hiding. They were adapting, engineering, and surviving.

Beneath the Eternal City: Rome’s Subterranean Secrets

Rome, the famed Eternal City, holds layer upon layer of history—not just in its ruins but deep beneath the cobblestones. Archaeologists have often said that digging in Rome is like slicing through a mille-feuille pastry: each stratum reveals another era.

The most famous underground structures here are the catacombs. Stretching for hundreds of kilometers, these burial sites were initially created by early Christians during times of persecution. They contain tens of thousands of tombs, frescoes, inscriptions, and early religious symbols that predate Christianity’s acceptance by the Roman Empire.

But the catacombs are only part of the story. Beneath the modern city lie ancient temples, aqueducts, cisterns, and even entire marketplaces. The Basilica of San Clemente is a powerful example: walking down through its levels, you pass through a 12th-century church, then a 4th-century church, and finally arrive in a 1st-century Roman house and pagan temple to Mithras. Each layer is a time capsule.

Rome’s underground, though often overshadowed by its grand monuments above, offers a far more intimate look into the daily lives and secret fears of its people. These buried spaces weren’t just used for burials but for rituals, storage, escape, and protection.

The Hidden Cities of China’s Ancient Dynasties

While China is celebrated for its imperial palaces and Great Wall, its subterranean cities are equally impressive and far more mysterious. One of the most striking examples is found near Xi’an, the former capital of multiple dynasties.

In 1974, farmers digging a well stumbled upon one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of the 20th century: the Terracotta Army. Thousands of life-sized clay soldiers stood guard over the tomb of Emperor Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor to unify China. But the burial complex itself—still only partially excavated—is rumored to be a sprawling underground city of palaces, weapons, rivers of mercury, and astronomical ceilings.

According to historical texts, the emperor was so obsessed with immortality that he commissioned an entire world underground to mimic the one he ruled in life. The toxic levels of mercury detected in the soil suggest that legends about mercury rivers might not be mere myths. Chinese archaeologists have long debated whether the tomb should be opened at all, as its fragile ecosystem could collapse under modern interference.

In another part of China, in the Loess Plateau of Shanxi and Shaanxi, millions of people to this day live in yaodongs—cave dwellings carved into soft soil cliffs. Though not cities in the traditional sense, these cave communities span generations and are a living example of how underground life can be more than just refuge—it can be home.

The Subterranean Metropolises of Naours and Beyond

France, too, holds secrets beneath its soil. In the quiet town of Naours in northern France lies a vast underground city carved from chalk. It has over 300 rooms and stretches nearly 2 miles. Unlike many subterranean structures born of fear, Naours was built in times of relative peace—around the 3rd century—but later repurposed during periods of war, especially during the Thirty Years’ War and later in World War I.

French monks, villagers, and eventually soldiers used these tunnels as hiding places. Walls are etched with graffiti from World War I, when Allied troops took shelter here. Many messages remain untouched—emotional time stamps left by young men in a world at war.

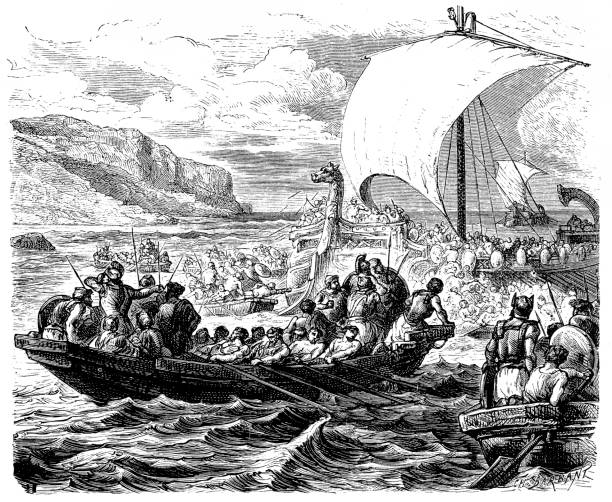

Across Europe, similar underground towns—called souterrains—appear in Ireland, Scotland, and Cornwall. Most were likely used for storing food and valuables, perhaps hiding from Viking raids. Their small entrances and winding passages suggest secrecy and defense.

These weren’t just cold bunkers. They were complex, purposeful designs—a fusion of practicality and ingenuity.

Subways of Stone: The Hidden Civilizations of South America

In the high Andes of Peru, the city of Cusco—once the capital of the Inca Empire—stands upon even more ancient foundations. Beneath it lie long-forgotten tunnels and chambers. Some legends claim these connect to Sacsayhuamán, an enormous fortress temple on a nearby hill.

While hard evidence is scarce due to modern building and restricted access, there are known subterranean structures throughout the Sacred Valley. The Incas, and possibly pre-Inca civilizations, carved not just temples and altars, but underground channels for water, storage, and ceremony.

At Tiwanaku in Bolivia, engineers discovered that the massive stones of Puma Punku may have been sourced from subterranean quarries miles away, then transported using methods still debated today. Subterranean temples like the Semi-Subterranean Temple also reveal a sacred function—built with extraordinary precision, aligned with astronomical events.

Unlike other underground cities built for hiding, many of South America’s subterranean spaces seem sacred, ceremonial, and cosmic in nature. They were built not out of fear but faith.

The Myth and Mystery of the Deros

Not all underground city stories stem from history or archaeology. Some come from the tangled webs of myth, conspiracy, and pseudoscience.

In the 1940s, Richard Shaver published strange stories in science fiction magazines claiming he had discovered ancient underground cities populated by malevolent beings called “Deros.” These creatures, he claimed, were the remnants of an ancient advanced race that had gone mad in the darkness.

Shaver’s stories sparked intense interest and controversy. While most scientists dismissed them as fantasy, some readers believed there was truth in his tales. His accounts were often linked to real places like Mammoth Cave in Kentucky or Mount Shasta in California—locations long tied to local Native American legends about hidden peoples or inner-earth realms.

Though discredited, the Shaver Mystery points to something deeper: our cultural obsession with what lies below. The idea of an inner Earth—whether as a scientific reality or a mythic realm—touches something primal in us. We fear the dark, but we are drawn to it. We bury our dead, but also our treasures, our fears, and our secrets.

Science, Survival, and the Future Underground

The age of underground cities is not over. In fact, it may be just beginning again.

In a world increasingly vulnerable to climate change, nuclear threats, overpopulation, and resource scarcity, the underground has once again become a frontier of possibility. Cities like Helsinki, Finland, are already building deep underground infrastructure: shopping malls, data centers, swimming pools, and shelters—designed not just for emergencies but as livable spaces.

In Singapore, engineers are exploring how to expand their city downward, creating underground science parks, storage areas, and even living quarters.

NASA, too, is interested in underground living—not on Earth, but on the Moon and Mars. Lava tubes on both celestial bodies offer natural shelter from radiation and extreme temperatures. One day, astronauts may carve cities into the sides of Martian cliffs, just as our ancestors once did in Cappadocia.

In this sense, the ancient underground cities are not relics. They are blueprints.

What the Darkness Teaches Us

The enduring mystery of underground cities is not merely architectural or historical—it is existential. They force us to consider the things we hide, the ways we survive, and the limits of what we think is possible.

These cities are echoes of fear, faith, and resilience. They are monuments to the human capacity for adaptation. They remind us that history is not always written in grand halls and golden temples. Sometimes it is etched into the walls of a tunnel, deep beneath the earth, in silence.

The subterranean world challenges our sense of linear progress. It proves that ancient people, with far fewer tools than we possess today, achieved astonishing feats—not only of survival but of imagination.

And as we stare down an uncertain future on a planet changing faster than we can predict, we may need to look down—not up—for answers.