For much of human history, Hansen’s Disease—commonly known as leprosy—has been one of the most feared and misunderstood illnesses. It evokes haunting images from ancient texts and medieval accounts: outcasts living on society’s margins, their bodies marked by a slow, creeping disfigurement. We’ve long believed its grip on the Americas began with European colonization, another cruel import in the wake of contact.

But that narrative just changed.

In a stunning breakthrough, a team of international researchers has uncovered genetic traces of leprosy in 4,000-year-old skeletons from Chile—thousands of years before Europeans ever set foot in the Americas. Their findings, published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, suggest that one form of the disease may have originated—or at least flourished—on the American continent far earlier than anyone imagined.

A Disease Lost in Time

Hansen’s Disease is caused by two bacteria: Mycobacterium leprae, the globally dominant strain, and Mycobacterium lepromatosis, a far rarer cousin discovered only in recent decades. Both strains attack the skin, nerves, and bones. If left untreated, the infection can lead to deformities, disability, and severe social stigma. And while modern medicine can treat it, access remains uneven across more than 100 affected countries.

Because of the way it changes bone structure over time, leprosy can sometimes leave behind a silent record in the skeletal remains of its victims. In Europe, Asia, and Oceania, such signs date back more than 5,000 years. But until now, no pre-colonial evidence had ever surfaced in the Americas. The absence led many to believe that leprosy arrived with the ships of European explorers.

That assumption is now under serious review.

Ancient DNA Meets South American Soil

The discovery came through the patient work of an international team led by Dr. Kirsten Bos, head of Molecular Paleopathology at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany. Alongside researchers in Argentina and Chile, Bos and her team examined ancient skeletons for subtle signs of disease—then turned to cutting-edge genetic analysis to see what secrets lay hidden in the bones.

“We’ve been studying pathological bone from the American context for over a decade,” Bos explained. “Ancient DNA has become a great tool that allows us to dig deeper into diseases that have had a long history in the Americas.”

One of those tools paid off in an unexpected way. In remains recovered from the arid lands of northern Chile, doctoral candidate Darío Ramirez from the University of Córdoba made a stunning discovery: genetic material from Mycobacterium lepromatosis, embedded in bones that were nearly 4,000 years old.

“At first, we were skeptical,” Ramirez recalled. “Leprosy has always been considered a colonial-era disease in this region. But the DNA analysis held up—it was clearly M. lepromatosis.”

Rebuilding a Forgotten Genome

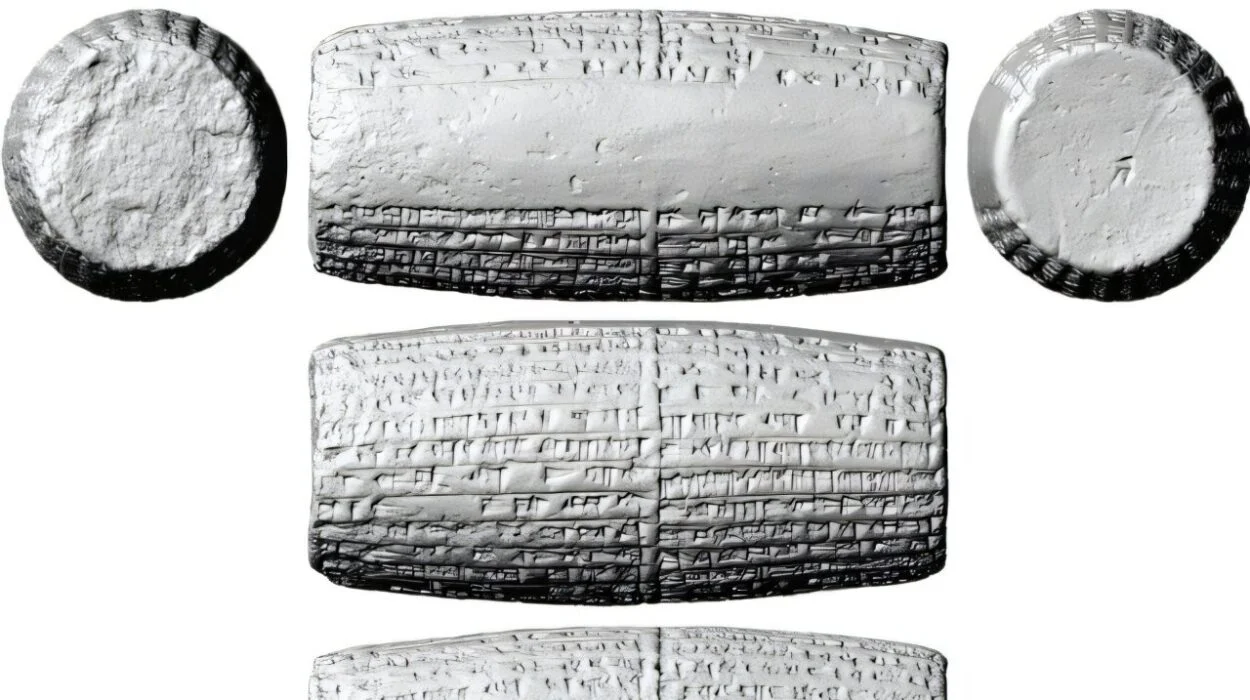

Reconstructing the genetic code of a bacterium that’s thousands of years old is a delicate, painstaking task. Ancient DNA is often degraded, fragmented, and contaminated. But in this case, the preservation was extraordinary.

“The pathogen was in amazing condition,” said Lesley Sitter, a postdoctoral researcher on Bos’s team. “That’s incredibly rare for ancient DNA, especially from samples this old.”

With enough material to work from, the team rebuilt the ancient genome of M. lepromatosis, allowing them to compare it with the few modern versions that exist. What they found was striking: while related to modern forms, this ancient version showed signs of being part of a longer, possibly independent evolutionary journey.

This finding suggests that M. lepromatosis was not a recent arrival to the Americas. It had been circulating—and causing disease—millennia before Columbus.

The Bigger Picture of Disease in the Americas

This discovery opens a new window into the vast and largely untold history of disease in the pre-contact Americas.

For nearly 20,000 years before European colonization, humans lived across the continent in diverse ecosystems—jungles, deserts, mountains, plains. Their bodies, and their immune systems, adapted to a host of regional challenges. But because so much was wiped out or buried beneath the wave of diseases that followed colonization, we’ve only scratched the surface of what diseases once haunted those populations.

“People often imagine the pre-Columbian Americas as being disease-free, but that’s not accurate,” said Bos. “It’s just that many of the diseases left behind little skeletal evidence, or they were buried beneath the epidemic chaos that followed contact.”

Thanks to new techniques in ancient DNA analysis, that story is changing. In recent years, Bos’s team has helped confirm that the family of bacteria responsible for syphilis may have originated in the Americas. Now, with this new evidence of leprosy’s deep roots, scientists are beginning to glimpse the contours of a vast, forgotten biological history.

A Disease of Humans—and More

Modern-day M. lepromatosis is considered rare. It has been detected in only a few human cases, most notably in Mexico and the Caribbean. Unlike M. leprae, which is known to infect armadillos in the southern United States, M. lepromatosis has so far not been detected in any non-human species in the Americas.

Curiously, its cousin M. leprae has recently been found in red squirrels in the United Kingdom and Ireland—an echo of the disease’s global reach and mysterious past.

Now that scientists know what to look for, they’re optimistic that more ancient cases will be uncovered. “This disease was present in Chile as early as 4,000 years ago,” said Professor Rodrigo Nores of the University of Córdoba. “Now that we know it was there, we can specifically search for it in other contexts—other regions, other skeletons.”

Rethinking Where It All Began

The discovery raises an even bigger question: Where did M. lepromatosis originate?

Until recently, the prevailing assumption was that leprosy, in all its forms, emerged in Eurasia around the Neolithic transition—roughly 7,000 years ago. That’s when humans began living in larger, denser communities, making it easier for diseases to spread and evolve.

But now, some experts—including Bos—believe that at least one branch of the leprosy family tree may have deeper American roots.

“So far, the evidence points in the direction of an American origin,” she said. “But we’ll need more ancient genomes, from different time periods and locations, to know for sure.”

It’s possible that the earliest settlers who migrated to the Americas from Asia brought the disease with them. It’s also possible that M. lepromatosis evolved independently on the continent. Either way, the discovery of its presence 4,000 years ago dramatically shifts the timeline—and our understanding of its spread.

A New Chapter in an Old Story

As science peels back the layers of time, it reveals not only what we didn’t know—but what we never thought to ask.

The story of leprosy has always been a global one, but now it’s also an ancient American one. And with every bone unearthed, every fragment of DNA decoded, we move closer to understanding how disease has shaped—and been shaped by—the human journey.

In a lonely desert tomb in Chile, microscopic strands of bacterial DNA survived for thousands of years, waiting for technology and tenacity to catch up. Now they’re telling their story—and it’s rewriting history.

Reference: Darío A. Ramirez et al, 4,000-year-old Mycobacterium lepromatosis genomes from Chile reveal long establishment of Hansen’s disease in the Americas, Nature Ecology & Evolution (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41559-025-02771-y