In a dark, quiet corner of the southern sky, 620 light-years from Earth, a vast molecular cloud silently churns with the potential for new stars. Known as the Chamaeleon cloud complex, this cosmic nursery is one of the most intriguing star-forming regions in our galaxy. Now, thanks to sensitive new radio observations, astronomers have just peeked deeper into its mysterious heart—and found five more young stars hiding in the dust.

Using the Australia Telescope Compact Array (ATCA), a team of astronomers led by Ernesto Garcia Valencia of the University of Sonora in Mexico has uncovered new stellar signals—radio whispers from stars just beginning their lives. Their research, published June 19 on the preprint server arXiv, adds new data to our evolving portrait of how stars, like our own Sun, first ignite in the darkness.

Listening to Starlight in Radio Frequencies

While optical telescopes capture the beauty of the night sky in familiar starlight, radio telescopes listen to the universe’s quiet murmurs—especially valuable when stars are still swaddled in thick blankets of gas and dust that obscure visible light.

This is exactly what makes ATCA so vital in regions like Chamaeleon. Instead of merely seeing the stars, it hears them: the radio emissions that leak from their spinning magnetic fields, heated material, or turbulent interactions.

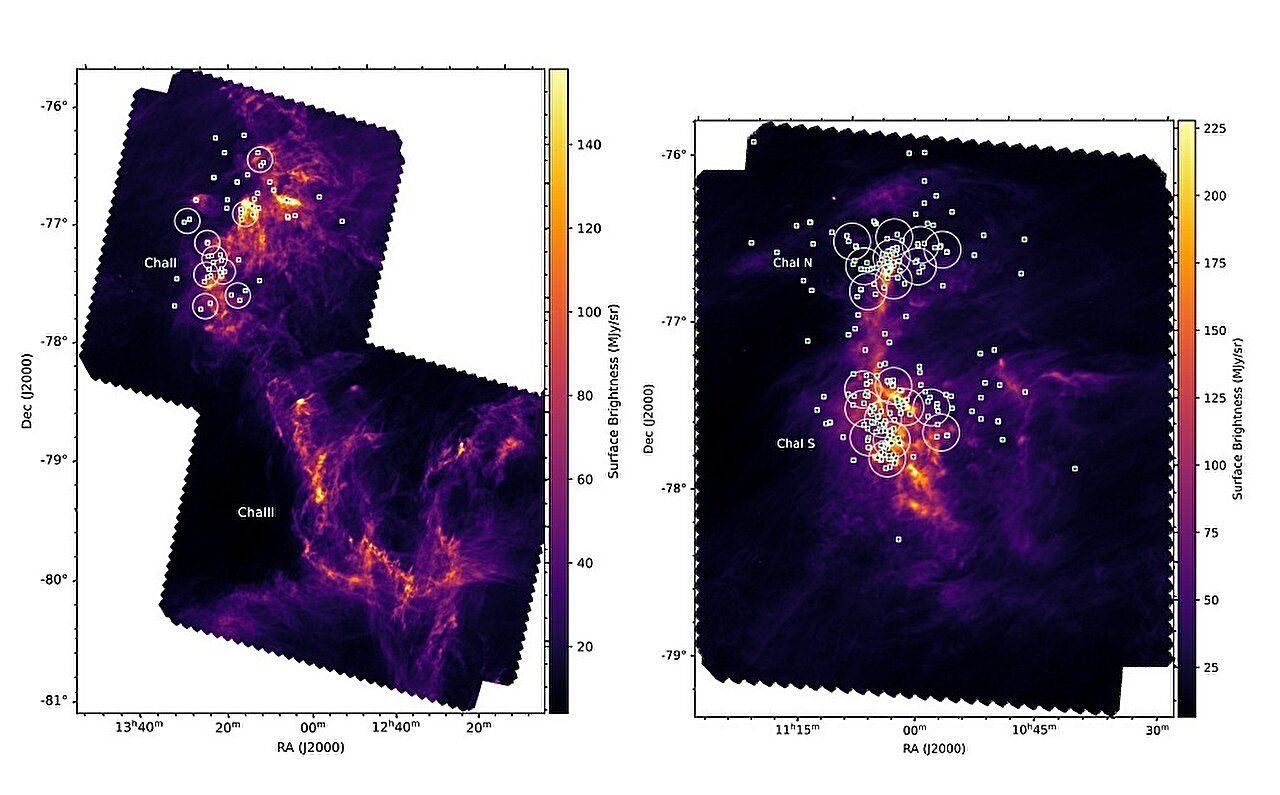

In this case, the team conducted a large-scale, high-resolution radio survey of the Chamaeleon cloud complex, which includes three major dark clouds: Chamaeleon I (Cha I), II (Cha II), and III (Cha III). These are not the kind of clouds you find in the Earth’s sky—they are frigid, thick concentrations of interstellar gas and dust, where gravity works slowly but steadily to pull matter together until stars are born.

Young Stars Emerge from the Dark

The survey detected radio emission from five young stars, each at a different point along the evolutionary road from interstellar gas to fully-fledged sun.

Three of the stars are T Tauri stars, a type of young, low-mass star still contracting under its own gravity and not yet stable like our Sun. These are the toddler stars of the galaxy—full of energy, spinning fast, and often surrounded by swirling disks of leftover material that could one day form planets.

One of the detected objects is a protostar—a star so young it hasn’t even reached the T Tauri phase yet. It’s still in the messy, violent process of forming, pulling in material and lighting up in the cold dark.

The fifth find is a Herbig Ae/Be star, a more massive cousin of the T Tauri stars, representing an early stage of higher-mass stellar development. These stars shine brighter and evolve faster, burning through their fuel more quickly than smaller stars like the Sun.

These detections paint a layered picture of stellar evolution happening all at once—some stars just forming, others moving steadily toward maturity, all within the same cloud.

A Closer Look with Long Baseline Precision

To dig deeper into the nature of these new radio sources, the team turned to the Australian Long Baseline Array (LBA)—a network of radio telescopes spread across Australia. The LBA offers higher spatial resolution, capable of spotting finer details and even detecting stellar companions.

This closer look revealed something extraordinary. One of the sources, named J11061540−7721567, appears to be a tight binary system—two stars gravitationally bound in a celestial dance. Based on the data, they likely orbit one another every 40 years, with a total mass close to that of our Sun, and a separation of just 12 astronomical units (about the distance between the Sun and Saturn).

Binary systems are important cosmic laboratories, offering clues about how stars interact, how they form, and even how planets might behave in their gravitational grip.

Tentative Stars and a Puzzle of Percentages

Intriguingly, the ATCA survey also revealed five additional faint radio sources that may also be young stars. These are still unconfirmed, but they suggest that the region may hold even more stellar infants waiting to be discovered.

Still, the detection rate—between 2.5% and 5% of known young stars in the surveyed region—is lower than in other star-forming regions. This could be due to limitations in sensitivity, or it could hint at something unique about Chamaeleon itself.

Why are fewer stars radiating in radio wavelengths here? Are the magnetic fields weaker, the environments quieter, or the stars less active? The team doesn’t yet know—but these kinds of questions are exactly what drive deeper exploration.

A Living Map of Cosmic Evolution

Star-forming regions like the Chamaeleon cloud are more than pretty celestial backdrops. They are living laboratories where astronomers can watch the universe build the building blocks of everything—stars, planets, and eventually life.

What makes Chamaeleon special is its structure. Cha I, with its population of around 250 pre-main sequence stars, is bustling with activity. Cha II is sparser, with less than 100 young stars. Cha III, on the other hand, appears to be a quiet womb, not yet begun the process of birthing stars at all. Observing all three allows scientists to compare different phases of a stellar nursery’s life, like watching a time-lapse of cosmic creation.

Each discovery adds one more data point to our understanding of the stellar life cycle—from gas, to gravity, to glorious fusion.

Listening to the Stars Yet to Be Born

The new findings in Chamaeleon are a testament to how far astronomy has come—not just in tools, but in imagination. Where once we gazed at the stars in awe, today we decode their earliest moments with precision.

By capturing the radio voices of baby stars, scientists like Garcia Valencia and his team are giving us the story of how stars like our own were born. And in doing so, they bring us closer to answering one of humanity’s oldest questions: Where did we come from?

For now, the Chamaeleon clouds continue to swirl in the southern sky—silent to our eyes, but not to our instruments. Somewhere in that darkness, more stars are being born. And thanks to the patient ears of radio astronomy, we’re learning to hear their first words.

Reference: Ernesto García Valencia et al, High resolution radio observations of the Chamaeleon star-forming region, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2506.15927