In a dusty Moroccan river valley nestled at the edge of the Atlas Mountains, a new chapter of human history has been unearthed—one that rewrites the role of northwest Africa in the rise of farming societies. At the Oued Beht site, archaeologists have uncovered what is now the oldest and largest known farming settlement in Africa outside of the Nile Valley, dating back to the Final Neolithic period, nearly 6,000 years ago. This extraordinary discovery bridges a long-standing archaeological gap and shines a powerful spotlight on the Maghreb’s central role in the emergence of complex societies across the Mediterranean.

The Maghreb: A Long-Ignored Crossroads of Ancient Worlds

Northwest Africa, or the Maghreb, has always held a strategic position. Flanked by the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the vast Sahara Desert to the south, it served as both a barrier and a conduit between continents. Its proximity to Europe—especially across the narrow Strait of Gibraltar—makes it an ideal node in the web of ancient migrations and exchanges. Yet, for reasons rooted in scholarly tradition and colonial-era neglect, the region’s deep past, particularly between 4000 and 1000 BC, has remained stubbornly obscure.

During this transformative period, known elsewhere for dramatic shifts such as the rise of the first cities in Mesopotamia and the early states of Egypt, the archaeological silence in the Maghreb has long puzzled researchers. Was this land isolated from the forces that birthed complex societies, or had its ancient voices simply been buried too deep to hear?

A Collaborative Effort Breaks the Silence

To answer these long-standing questions, archaeologists Youssef Bokbot of Morocco’s National Institute of Archaeological Sciences and Heritage (INSAP), Cyprian Broodbank of the University of Cambridge, and Giulio Lucarini of Italy’s CNR-ISPC and ISMEO launched an ambitious field project in the Oued Beht valley. Combining expertise in paleoenvironmental studies, ancient technology, and social archaeology, the team conducted a multidisciplinary excavation that revealed an astonishing picture of prehistoric life in the Maghreb.

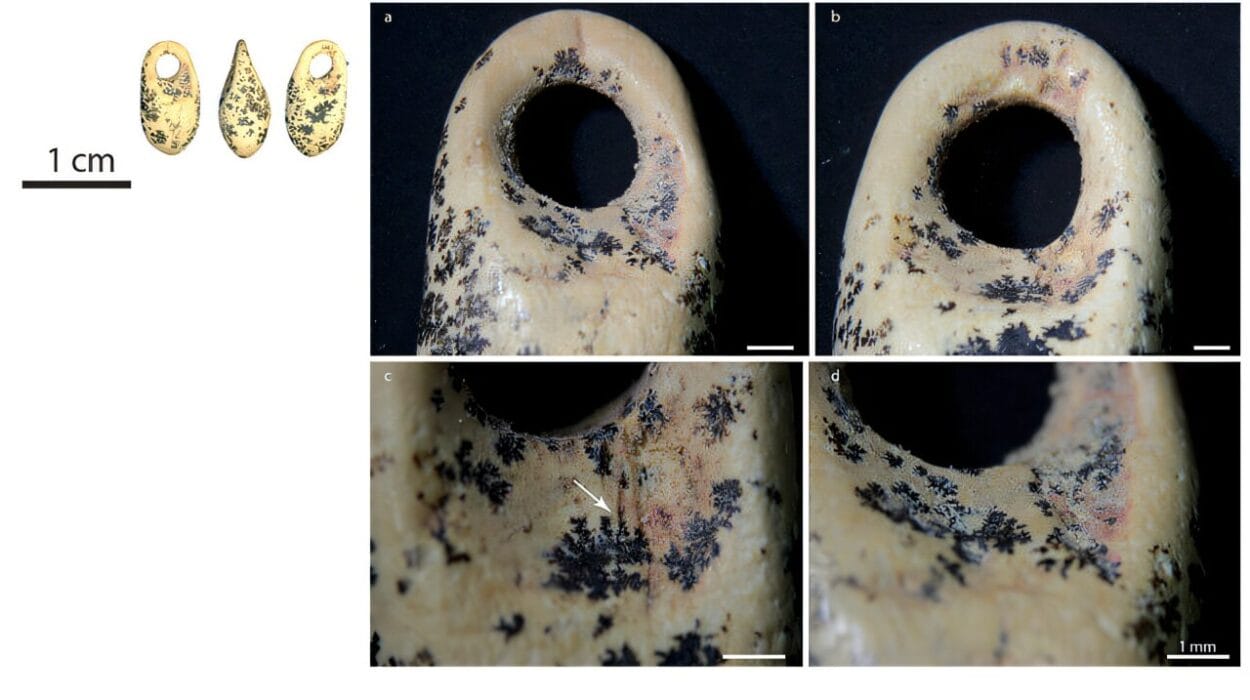

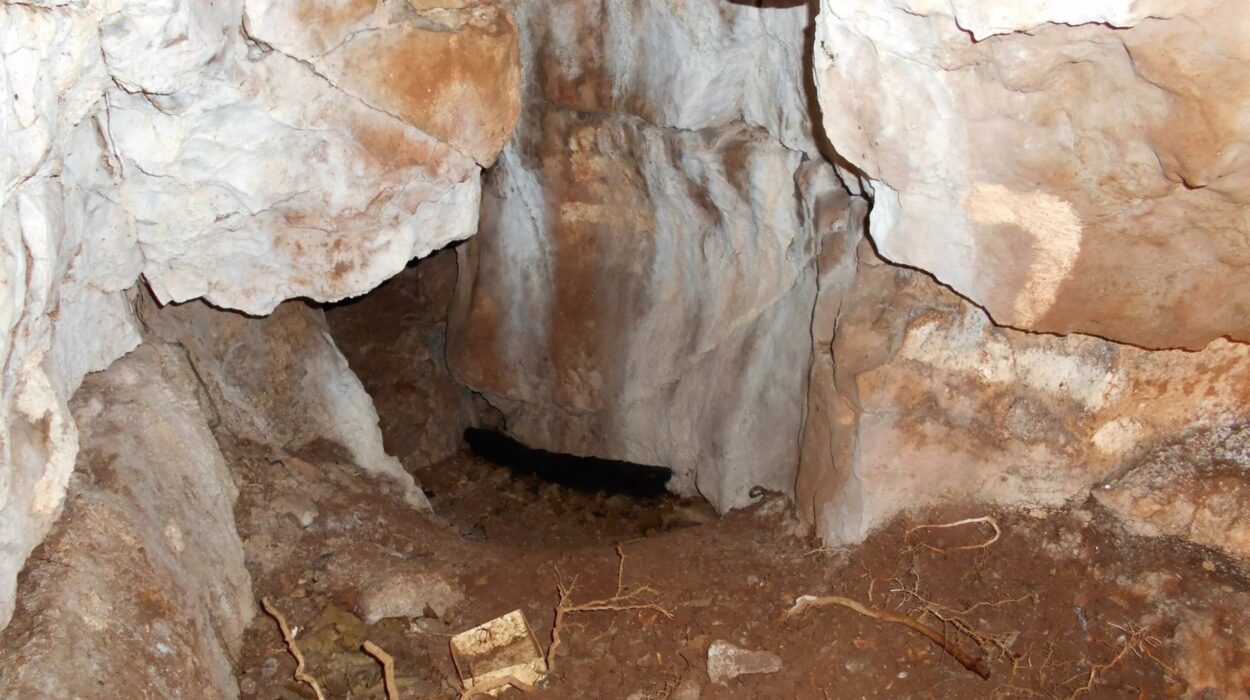

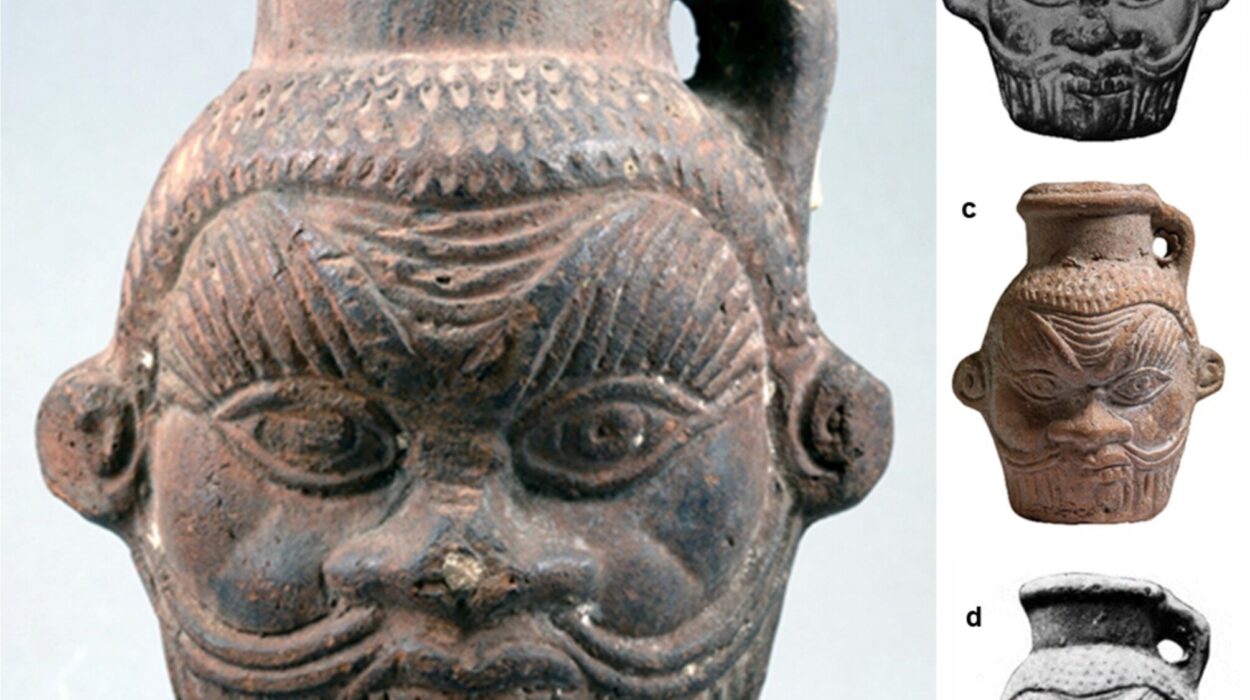

The excavation site yielded a wealth of well-preserved artifacts—lithic tools, elaborately decorated pottery, domesticated grains and legumes, animal bones from managed herds, and extensive subterranean storage pits. These remains were not scattered traces of temporary habitation; they told the story of a permanent, organized farming community of significant scale—possibly comparable in size to early urban centers such as Bronze Age Troy.

Agriculture and Architecture: A Flourishing Neolithic Heartland

What makes Oued Beht so exceptional is the clarity with which it demonstrates the presence of a fully developed agrarian society at a time when such communities were thought to be rare or nonexistent in this part of Africa. The deep storage pits point to long-term planning, surplus production, and food security strategies typical of sedentary farmers. Moreover, the variety and quantity of cultivated crops and domesticated animals provide undeniable proof of advanced agricultural techniques.

Notably, these early Maghrebi farmers appear to have developed their economy and architecture independently, though in dialogue with surrounding regions. The layout of the settlement and its material culture suggest both local innovation and external connections—an echo of the complex dynamics that shaped early Mediterranean civilizations.

Echoes Across the Strait: Iberian Links and African Roots

Perhaps the most thrilling dimension of this discovery lies in the evidence of long-distance interactions. Similar storage pits have been identified in contemporaneous sites across the Strait of Gibraltar in southern Iberia, alongside exotic materials such as ostrich eggshells and ivory that could only have originated in Africa. These artifacts had long hinted at contact, but until now, the African side of the story was missing.

The Oued Beht findings provide the crucial missing link. They reveal not only that northwestern Africa was actively participating in the cultural exchanges that defined the western Mediterranean during the fourth millennium BC, but that it may have been one of the engines driving that exchange. This challenges the traditional Eurocentric narrative that portrays innovation and progress as flowing outward from Europe and the Near East. Instead, it underscores a far more nuanced and interconnected prehistoric world in which African communities played leading roles.

Rethinking the Prehistoric Mediterranean

The implications of the Oued Beht discoveries ripple far beyond the borders of Morocco. They force a reassessment of how scholars understand the development of Mediterranean societies and the flow of ideas, technologies, and cultures across the region. For over a century, the southern coast of the Mediterranean—west of Egypt—was often treated as a blank spot on the map of prehistoric progress. Now, thanks to careful excavation and rigorous analysis, that blank spot has begun to fill with vivid color.

As Professor Broodbank reflects, “For over thirty years I have been convinced that Mediterranean archaeology has been missing something fundamental in later prehistoric North Africa. Now, at last, we know that was right.” These findings vindicate decades of academic suspicion that the absence of evidence was due less to a lack of ancient activity, and more to a lack of modern archaeological attention.

An African Community at the Heart of Mediterranean History

The people of Oued Beht were not passive recipients of Mediterranean influence; they were active contributors to a shared social and technological world. The final centuries of the Neolithic in the Maghreb saw the birth of something profound—distinctly African communities that helped shape the early chapters of civilization across continents.

By embedding Oued Beht within a broader Mediterranean-Atlantic framework, the research team emphasizes the importance of seeing prehistoric development not as isolated local phenomena, but as part of a co-evolving network. Whether through trade, migration, or parallel innovation, these ancient farmers of the Maghreb were shaping—and being shaped by—their world.

Rediscovering Africa’s Place in the Human Story

The excavation of Oued Beht is more than just an archaeological milestone; it is a reminder of the need to widen our historical lens. Too often, the global narrative of human civilization has marginalized Africa’s role outside of Egypt and the Nile Valley. But here, in a Moroccan valley long ignored by mainstream scholarship, is compelling proof of Africa’s dynamism, creativity, and interconnectedness at a formative time in world history.

In the coming years, further research at Oued Beht and other sites in the region may reveal even more about the rhythms of life, belief systems, and innovations of these early farmers. For now, their rediscovery stands as a triumph of archaeology—and a long-overdue correction to our understanding of the ancient world.

Reference: Antiquity (2024). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2024.101