More than 2.6 million years ago, long before the first sparks of fire or the rise of civilizations, small bands of ancient humans gathered along the shores of what is now Lake Victoria in southwestern Kenya. Life was raw and precarious: hippos lurked in the shallows, predators prowled the plains, and survival demanded ingenuity.

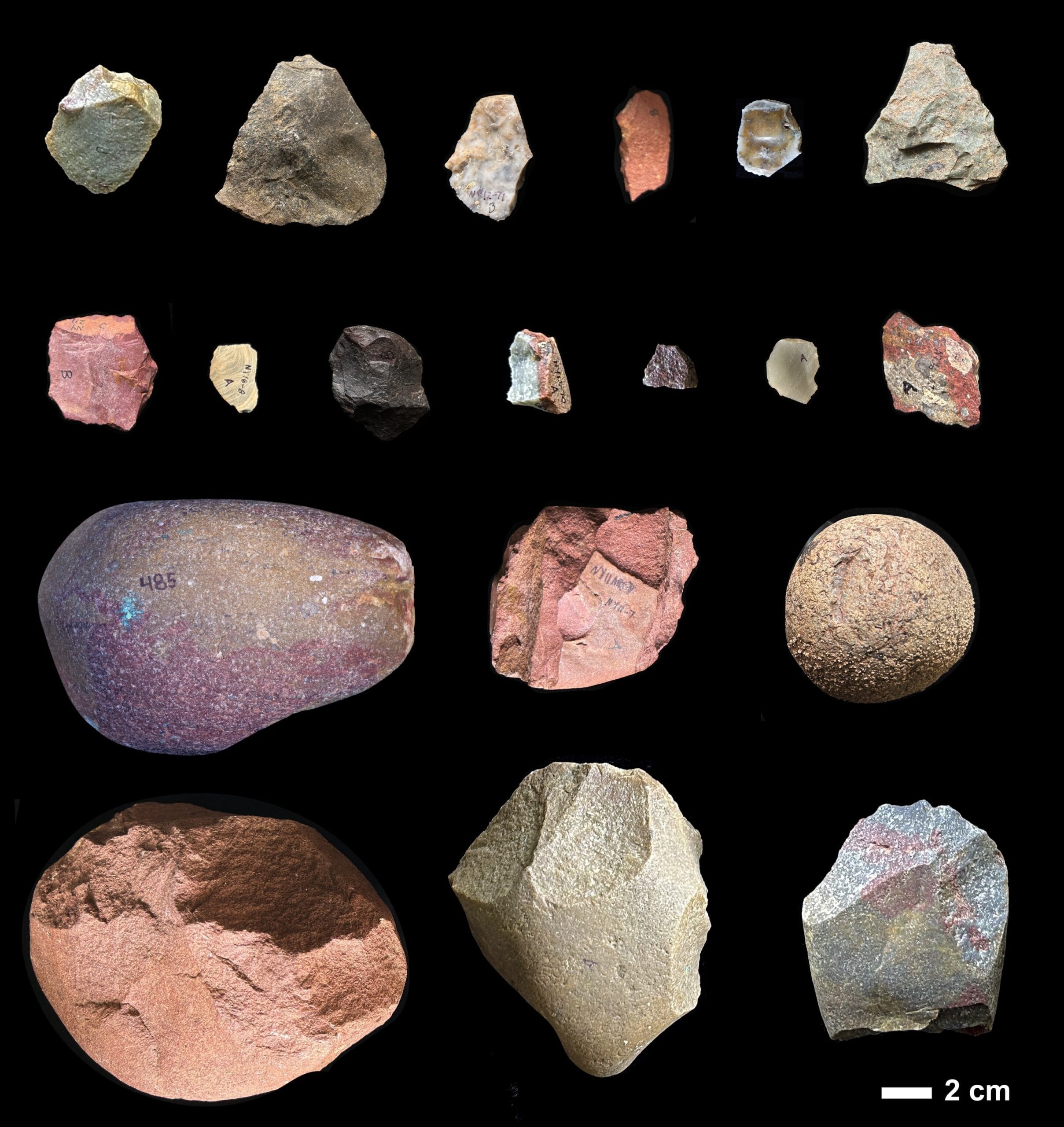

Amid this world, our ancestors held in their hands something extraordinary — rough stone tools. These objects, known as the Oldowan toolkit, were simple by today’s standards, yet revolutionary for their time. With them, early humans pounded fibrous plants, split open animal bones, and sliced through the thick hides of giant prey.

A new study, led by researchers at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, and Queens College, has now revealed that these tools were not just opportunistic scraps of rock. They were carefully chosen materials, carried from distant sources, and shaped with purpose. This discovery pushes the story of human planning, foresight, and innovation far deeper into prehistory than scientists once believed.

Stones That Traveled Miles

The archaeological site of Nyayanga, perched on Kenya’s Homa Peninsula, has yielded hundreds of stone artifacts alongside butchered hippopotamus bones. What astonished researchers was not just what the tools could do, but where they came from.

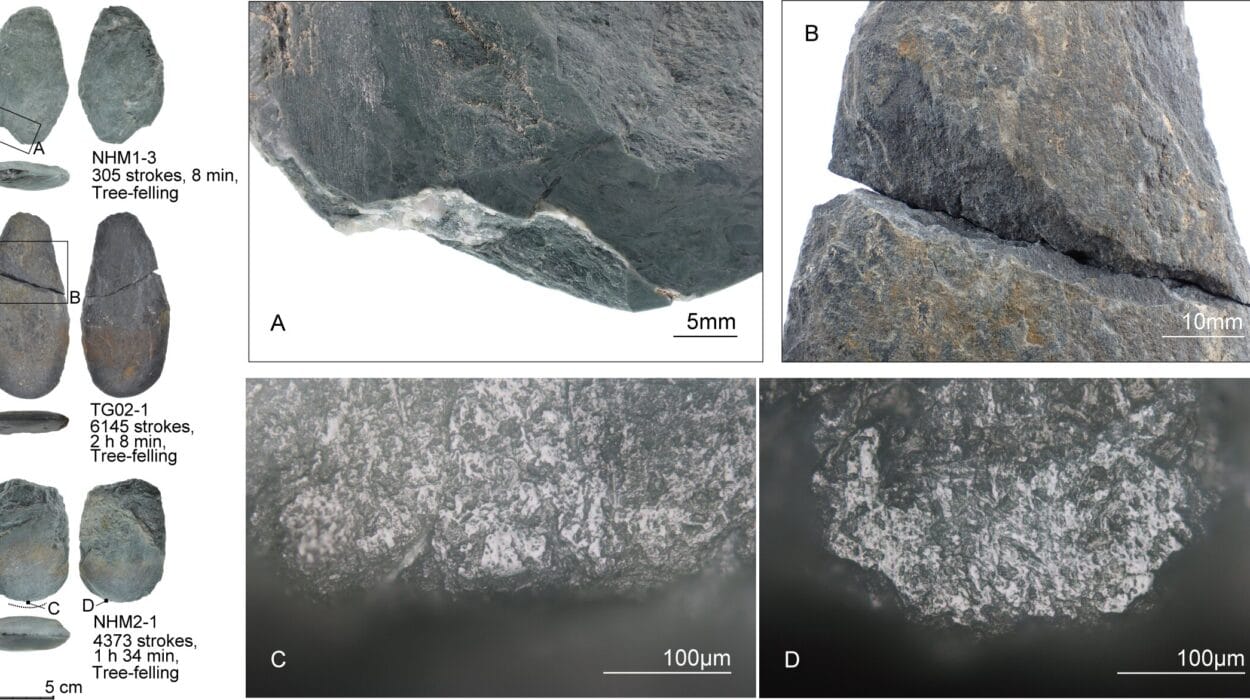

Geochemical analysis showed that many of these stones were not native to Nyayanga’s soil. Instead, they were volcanic and metamorphic rocks — rhyolite and quartzite — sourced from drainage basins located more than six miles away.

For early humans with no pack animals, carts, or roads, carrying heavy stones such distances was no small feat. It required planning: an awareness of where good toolmaking stone could be found, an understanding of where food was abundant, and a decision to bridge the two. In short, it revealed a mind capable of mapping landscapes and thinking ahead.

“People often focus on the tools themselves,” said Rick Potts, senior author of the study and the Smithsonian’s Peter Buck Chair of Human Origins. “But the real innovation of the Oldowan may actually be the transport of resources from one place to another.”

The Earliest Signs of Planning

Until now, the oldest evidence of humans deliberately transporting stone over long distances dated back around two million years. The Nyayanga discoveries push that timeline back by at least 600,000 years, into a period when tool use was still in its infancy.

That change is profound. Carrying stones is not simply about muscle — it reflects foresight. It shows that our ancestors could weigh future needs against present effort, selecting the right materials to bring back to camp, where they could be transformed into cutting flakes or pounding tools.

“It’s surprising,” said Emma Finestone, lead author of the study and curator at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. “The Nyayanga assemblage is early in the Oldowan, and we previously thought longer transport distances might only come later in our evolutionary story. Clearly, the capacity for planning was present from the very beginning.”

Life on the Edge of Survival

The Nyayanga site has also preserved a vivid picture of how these tools were used. Excavations uncovered the butchered remains of hippopotamuses, massive animals weighing several tons. Marks etched into their bones reveal that stone flakes had been used to slice through flesh, while pounding tools cracked open tough surfaces to access marrow.

For small-bodied hominins living without fire or advanced weapons, hippos would have been both a prize and a peril. A single animal could provide days of food, but approaching one was dangerous. The Oldowan tools gave our ancestors an edge — transforming carcasses into resources and expanding the range of foods they could consume.

“Hominins were using stone tools for a variety of pounding and cutting tasks,” explained Thomas Plummer, co-author and professor at Queens College. “The diversity of activities suggests that, even at this early stage, stone tools enhanced adaptability.”

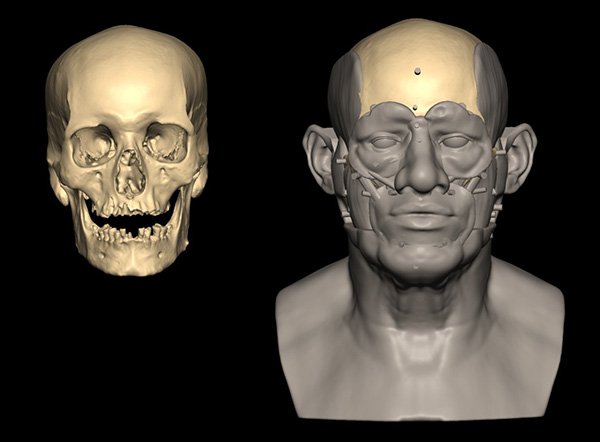

Who Were the Toolmakers?

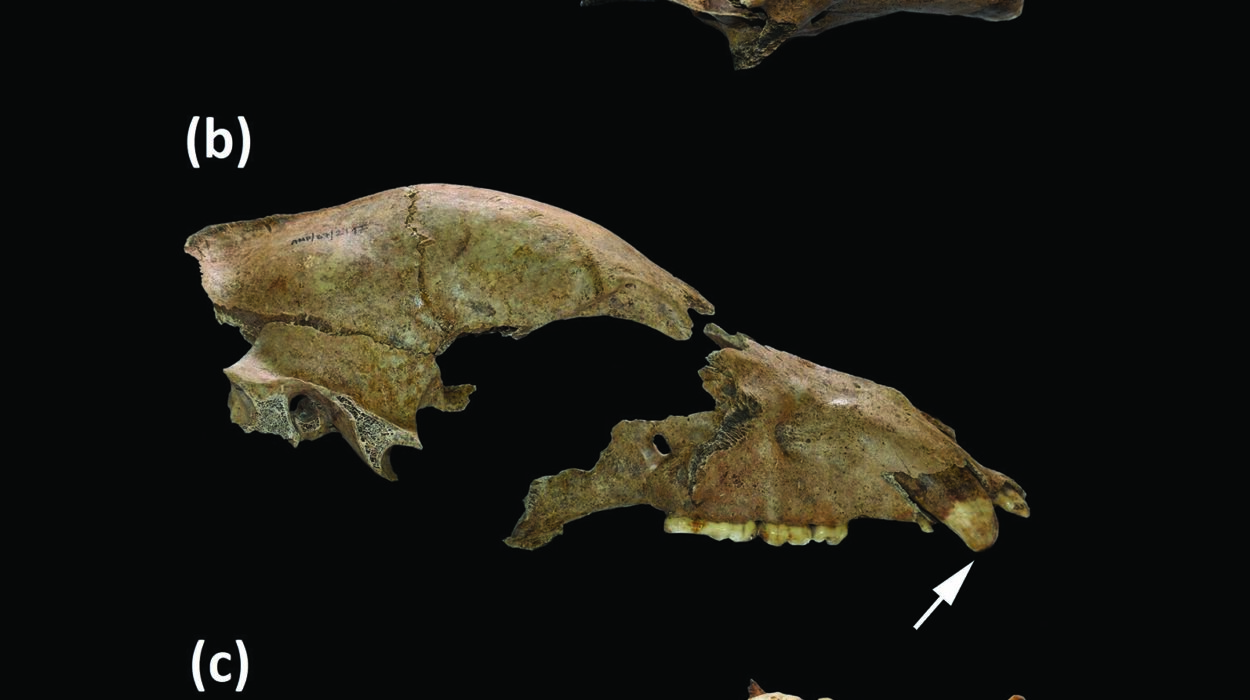

The question of who made these tools lingers. At Nyayanga, researchers discovered fossil teeth from Paranthropus, a robust hominin with powerful jaws and large molars. For decades, scientists assumed that only members of the genus Homo — our direct ancestors — crafted stone tools. The Nyayanga evidence complicates that view.

“Unless you find a hominin fossil actually holding a tool, you can’t say definitively which species made them,” Finestone noted. “But our findings suggest that toolmaking may have been more widespread across different hominin groups than we once thought.”

If true, this broadens our view of intelligence in the ancient world. Tool use may not have been the sole domain of Homo, but a shared strategy among multiple human lineages, each finding ways to extend their reach with stone.

The First Step in a Long Journey

The discovery at Nyayanga underscores a timeless truth: humans are a species of toolmakers and travelers. The instinct to seek, carry, and transform raw materials is etched deep into our evolutionary past.

From carrying rocks across Kenyan landscapes millions of years ago to carrying smartphones and satellites across the globe today, the story of technology is also the story of humanity’s survival.

“Humans have always relied on tools to solve adaptive challenges,” Finestone reflected. “By understanding how this relationship began, we can better see our connection to it today — especially as we face new challenges in a world shaped by technology.”

The Legacy of Stone and Memory

As we hold these chipped stones today, they appear humble, unremarkable. Yet in their sharp edges and worn surfaces lies a revolution — the dawn of human foresight. At Nyayanga, our ancestors looked beyond the immediate moment. They imagined a future need, they planned, they carried, and they created.

These tools are more than artifacts; they are echoes of intention. They remind us that the ability to shape the world around us — to envision what might be, and to act upon it — began with simple stones carried across ancient plains.

In those first steps of resourcefulness lies the seed of everything that followed: fire, art, language, science, and the endless horizon of human imagination.

More information: Emma Finestone, Selective use of distant stone resources by the earliest Oldowan toolmakers, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adu5838. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adu5838