Imagine standing on the edge of a vast African plain nearly three million years ago. The air is dry and filled with the scent of smoke from distant fires. Rivers snake unpredictably through the landscape, sometimes vanishing under the grip of drought. Across this shifting terrain, early humans chip away at stones, shaping them into sharp-edged tools—their lifeline in a world of uncertainty.

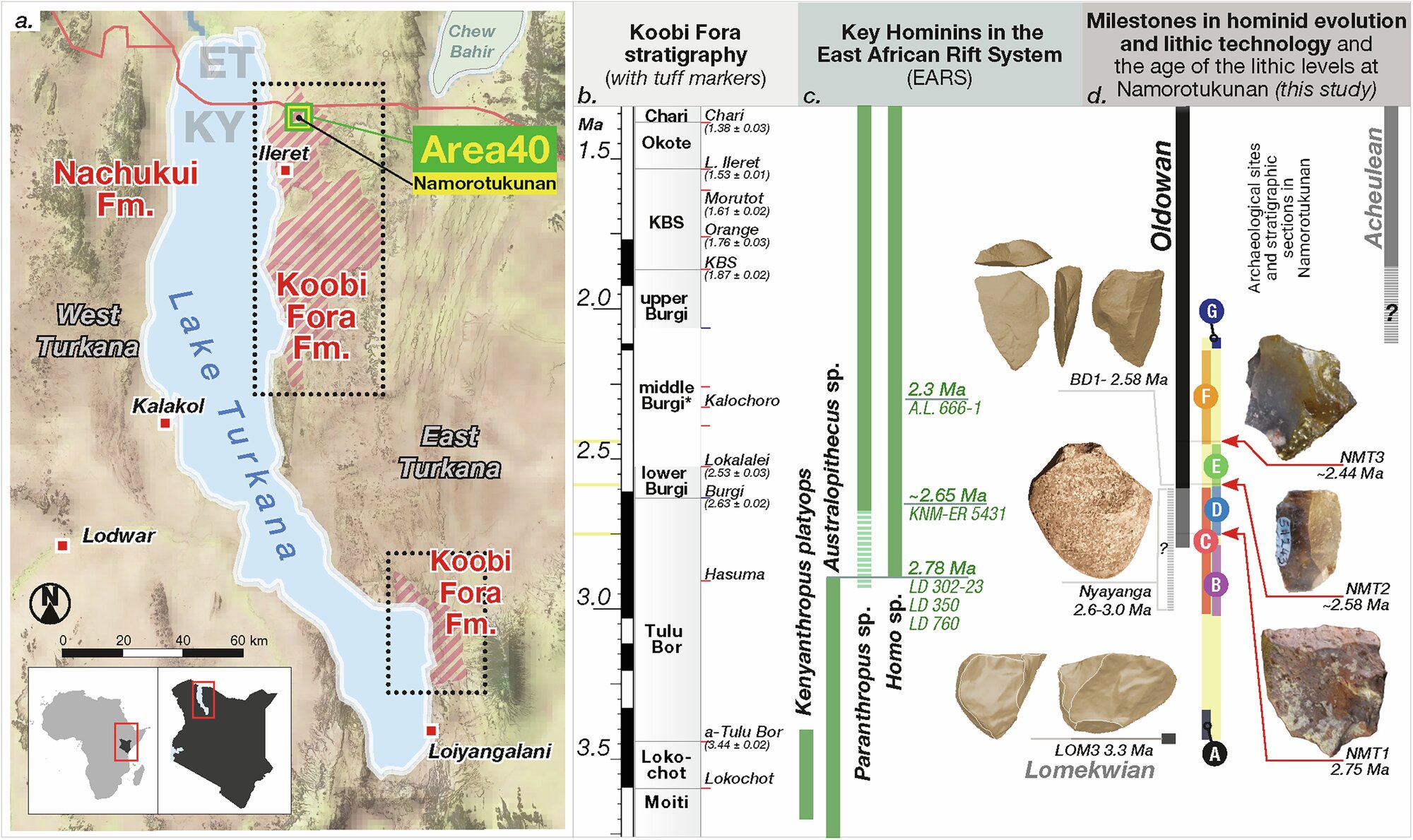

These tools, crafted by ancient hominins in Kenya’s Turkana Basin, tell a story of extraordinary endurance and innovation. According to a groundbreaking study published in Nature Communications, titled “Early Oldowan technology thrived during Pliocene environmental change in the Turkana Basin, Kenya,” scientists have unearthed some of the oldest and longest-lasting examples of early human technology ever discovered.

At a site called Namorotukunan, researchers found thousands of stone artifacts dating between 2.75 and 2.44 million years ago. For nearly 300,000 years, generations of toolmakers returned to this place, shaping similar tools in the same style—even as the world around them changed beyond recognition.

A Window into Deep Time

The Turkana Basin, in northern Kenya, is one of the most important places on Earth for understanding human origins. Its layers of ancient sediments are like pages in a geological book, recording millions of years of environmental change. In this setting, researchers discovered stone flakes, cores, and sharp-edged cutting tools—collectively known as Oldowan tools, the earliest form of human technology.

These were not crude or random objects. Each stone was carefully struck to produce a sharp edge, capable of cutting meat, scraping plants, or breaking bones. They were, in essence, the first multi-purpose tools—primitive yet ingenious instruments that expanded what early humans could eat and how they could live.

At Namorotukunan, these tools appeared in layers spanning hundreds of millennia, revealing not a single moment of invention but an unbroken tradition. “This site reveals an extraordinary story of cultural continuity,” said David R. Braun, lead author of the study and professor of anthropology at George Washington University. “What we’re seeing isn’t a one-off innovation—it’s a long-standing technological tradition.”

This finding challenges the common idea that early human progress was marked by sudden bursts of creativity. Instead, it suggests a deep-rooted continuity of knowledge, passed from one generation to the next—a silent inheritance of skill that shaped our species long before the appearance of modern humans.

Tools Through Fire and Drought

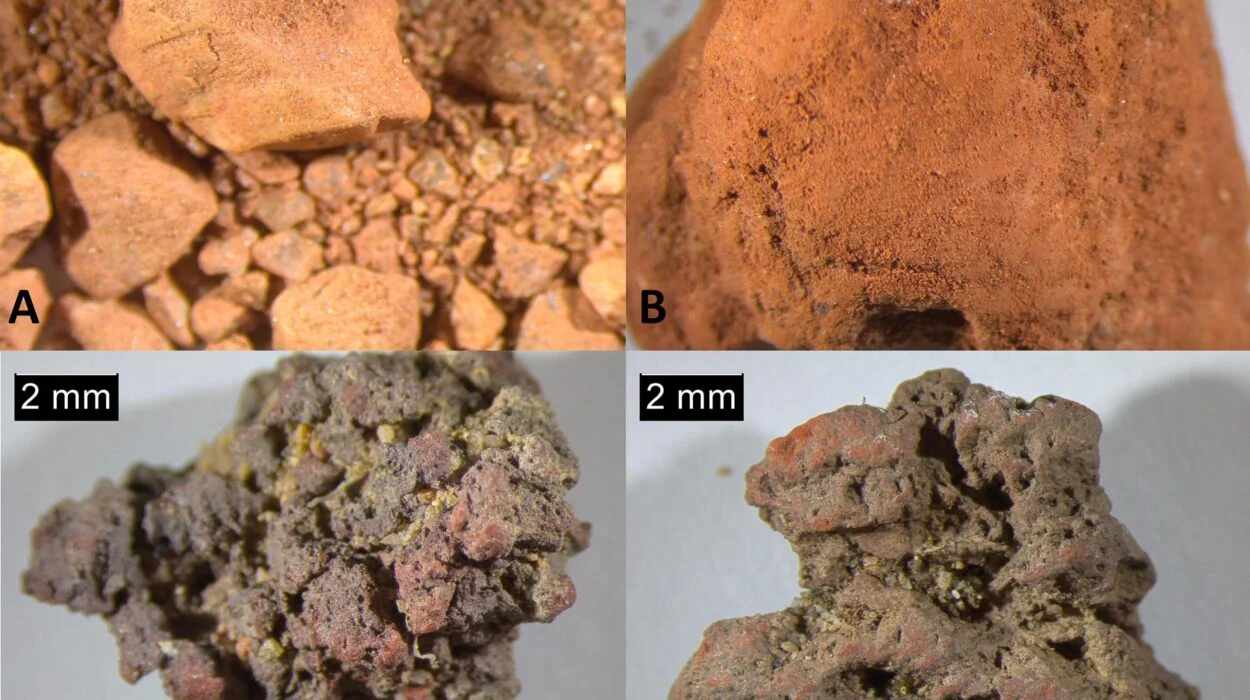

To understand the significance of these discoveries, the research team pieced together an intricate picture of what life was like in the Turkana Basin during the Pliocene epoch. Using volcanic ash dating, magnetic signals preserved in rocks, and chemical analyses, they reconstructed a timeline of environmental chaos—intense droughts, floods, and recurring wildfires that transformed the land.

“The plant fossil record tells an incredible story,” said Rahab N. Kinyanjui from the National Museums of Kenya and the Max Planck Institute. “The landscape shifted from lush wetlands to dry, fire-swept grasslands and semideserts. As vegetation shifted, the toolmaking remained steady. This is resilience.”

Even as rivers changed course and habitats disappeared, the stone tools remained consistent in design and craftsmanship. This unyielding tradition speaks to a powerful truth: early humans had already learned how to adapt through technology.

“Namorotukunan offers a rare lens on a changing world long gone—rivers on the move, fires tearing through, aridity closing in—and the tools, unwavering,” said Dan V. Palcu Rolier, a senior scientist at GeoEcoMar, Utrecht University, and the University of São Paulo. “For roughly 300,000 years, the same craft endures—perhaps revealing the roots of one of our oldest habits: using technology to steady ourselves against change.”

The Birth of Technological Tradition

The tools of Namorotukunan belong to the Oldowan tradition, named after Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, where similar artifacts were first discovered in the early 20th century. These tools represent the dawn of technological thinking—the point when our ancestors realized that nature’s materials could be reshaped to serve their needs.

By striking one stone against another, they produced razor-sharp flakes that could slice meat or plant fibers, unlocking new sources of food and nutrients. This small leap of creativity had enormous evolutionary consequences. Access to meat provided more calories and nutrients, fueling brain growth and supporting the long journey toward becoming human.

“These finds show that by about 2.75 million years ago, hominins were already good at making sharp stone tools, hinting that the start of the Oldowan technology is older than we thought,” said Niguss Baraki of George Washington University.

The tools also provide evidence of meat consumption. At Namorotukunan, animal bones bearing cut marks suggest deliberate butchery—proof that early humans were not just scavengers but skilled users of tools to access meat. “At Namorotukunan, cut marks link stone tools to meat eating, revealing a broadened diet that endured across changing landscapes,” explained Frances Forrest of Fairfield University.

Climate Chaos and Human Ingenuity

The Pliocene epoch, spanning from about 5.3 to 2.6 million years ago, was a period of dramatic climate fluctuations. Shifting rainfall patterns, recurring fires, and expanding grasslands transformed ecosystems across Africa.

In such a volatile environment, survival required flexibility. Animals migrated or went extinct, and vegetation zones shifted over hundreds of kilometers. But at Namorotukunan, early humans found stability not in the land, but in their tools.

The Oldowan toolkit was adaptable—a kind of technological insurance policy. It could process a wide range of materials, from animal flesh to tough roots and woody plants. This versatility helped early hominins maintain a consistent way of life even as their surroundings changed drastically.

“Our findings suggest that tool use may have been a more generalized adaptation among our primate ancestors,” said Susana Carvalho, director of science at Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique and senior author of the study.

This insight reframes how we understand early human behavior. Rather than a sudden spark of intelligence, it points to a slow, steady mastery of survival through innovation. The ability to make and maintain tools—over centuries and across changing worlds—became one of humanity’s defining traits.

A Heritage Written in Stone

The story of Namorotukunan is more than an archaeological discovery—it is a story about who we are. Every strike of stone against stone echoes across millions of years, connecting us to ancestors who faced uncertainty and responded with creativity.

They lived without fire, agriculture, or language as we know it. Yet they understood something essential: that the world could be shaped by human hands. Their tools became extensions of their minds—a physical manifestation of thought, learning, and memory.

In those sharp edges, we see the origins of all technology that followed. The first chipped stone led eventually to the first wheel, the first plow, the first computer. Every innovation in human history traces its lineage to these early experiments in the Turkana Basin.

The Power of Continuity

For almost 300,000 years, the toolmakers of Namorotukunan practiced a craft that remained remarkably consistent. This endurance is not a sign of stagnation, but of stability—a deep cultural rhythm that bound generations together through shared knowledge.

It suggests that early humans valued reliability over novelty. Their world demanded resilience, not constant reinvention. In this light, the Oldowan tradition stands as one of the greatest human achievements—a technology that endured longer than any civilization, longer than written language, longer even than our own species.

As David R. Braun observed, “What we’re seeing isn’t a one-off innovation—it’s a long-standing technological tradition.” That tradition—the passing of skill from hand to hand, mind to mind—is the foundation upon which all of human culture rests.

Echoes of the First Technologists

Today, standing in the Turkana Basin, the landscape appears stark and silent, but beneath the dust lies the evidence of a living legacy. The hands that once struck stone in this place set in motion a chain of ingenuity that continues to this day.

The discovery at Namorotukunan is not just about the past—it is about understanding how deeply technology is woven into the human story. It shows that our relationship with tools is not a modern phenomenon; it is an ancient dialogue between creativity and survival.

In a world once ruled by fire and drought, the first technologists found their way forward—not by changing the environment, but by mastering the ability to adapt. And in doing so, they revealed something timeless about humanity: our enduring will to endure.

More information: David R. Braun et al, Early Oldowan technology thrived during Pliocene environmental change in the Turkana Basin, Kenya, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-64244-x