When people imagine the end of Roman Britain around AD 400, they often picture a land slipping quickly into silence. Roman roads crumbled, villas fell into disrepair, and the organized economy of empire seemed to dissolve into a so-called “Dark Age.” For generations, historians assumed this collapse extended to industry as well. Large-scale lead and iron production—the backbone of Roman Britain’s contribution to empire—was thought to have vanished almost overnight.

But a new study suggests this picture is far too simple. Deep beneath the soil of Yorkshire, in the former Roman town of Aldborough, a five-meter-long sediment core has preserved a hidden story. Layer by layer, it records traces of metal pollution from ancient furnaces and workshops. And what it reveals is striking: the metal industry in Britain did not collapse when the legions departed. Instead, production continued, even expanded for a time, before encountering an unexpected crash more than a century later.

The Roman Gift of Industry

The Romans were more than conquerors; they were builders of systems. Their roads, aqueducts, sanitation networks, and urban planning left a legacy that still echoes today. Among their less visible but equally transformative contributions was large-scale industrial activity. Roman Britain became a hub for extracting and processing metals, especially lead and iron. These resources were essential for everything from plumbing and coinage to weapons and construction.

By the third century, Britain was recognized across the empire as a major center of metal production. Yet after the fourth century, written sources fall silent. No inscriptions record new lead mines, and archaeological traces seemed to thin. For many historians, this silence became evidence: surely the industry had withered along with Rome’s authority.

A Window Beneath the Soil

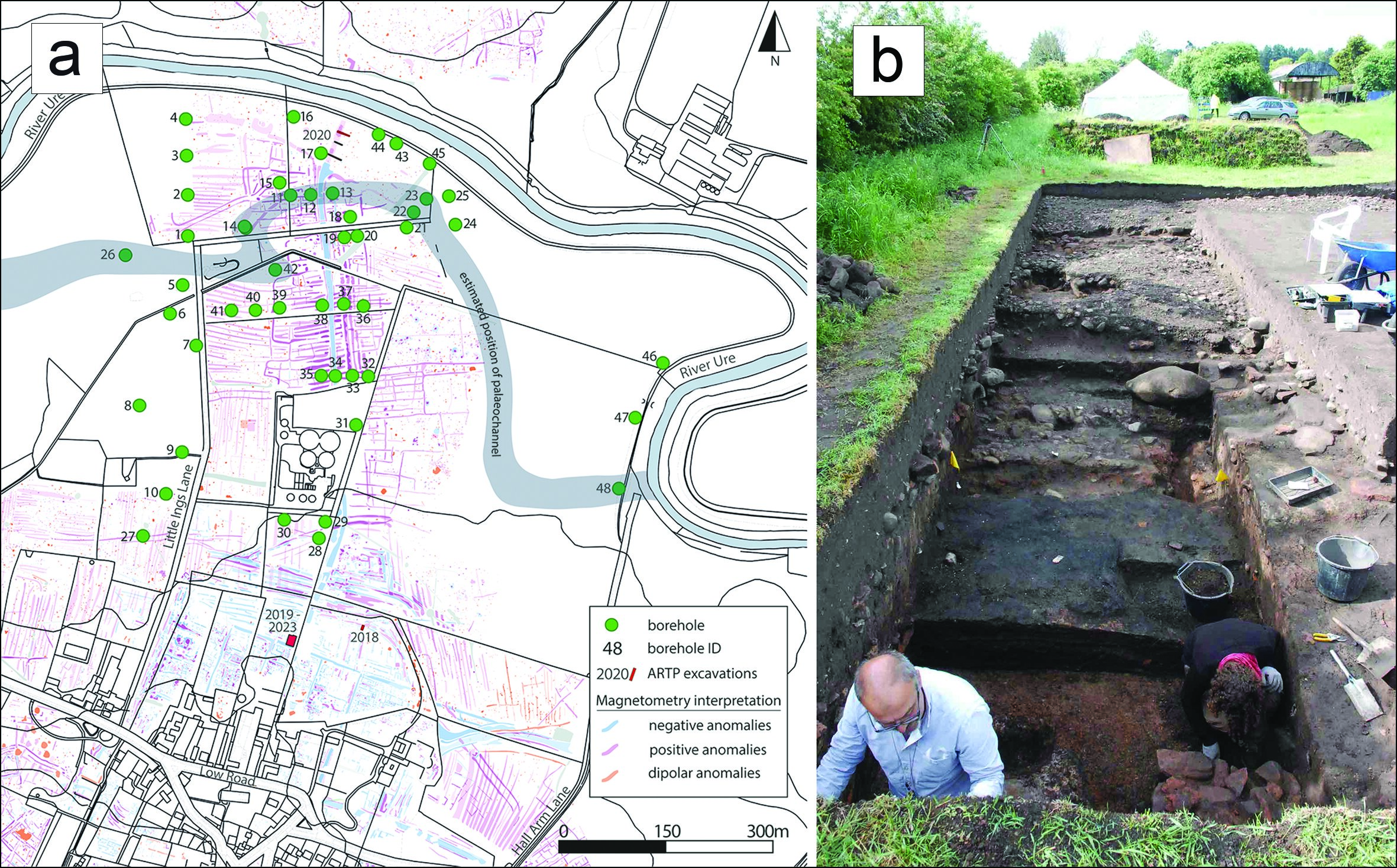

To test whether this assumption held true, a team of researchers from the Universities of Cambridge, Nottingham, and other UK institutions turned to a method that bypasses written records altogether. They extracted a sediment core from Aldborough, once the bustling tribal town of the Brigantes and a major Roman industrial site.

Sediment cores are like natural history books, with each layer capturing the chemical fingerprint of its time. In Aldborough’s core, researchers found traces of heavy metals such as lead, copper, and zinc—direct evidence of smelting and ore processing. Unlike fragmentary artifacts or scarce inscriptions, this record is continuous and unbroken, spanning from the fifth century to the present day.

What emerged was a timeline of Britain’s industrial heart, preserved grain by grain, year by year.

Continuity Beyond the Empire

The findings overturned centuries of assumption. Instead of a dramatic collapse in AD 400, the record shows steady or even increasing levels of metal pollution into the fifth century. This suggests that local communities, freed from Roman control, continued to exploit the resources and technologies left behind.

Coal, already used in Roman times, may have fueled this post-imperial industry. Ores still lay abundant in the region, and the skills to work them had not vanished. Far from retreating into isolation, some parts of Britain may have maintained vibrant, organized economies well into the so-called Dark Ages.

It was not until around AD 550–600 that the record shows a sudden, sharp decline. Metal production, it seems, faltered not with the fall of Rome but with something more insidious.

The Plague and the Great Crash

Why did metal production collapse in the late sixth century? The answer may lie not in politics but in disease. Historical sources and modern DNA evidence point to outbreaks of bubonic plague across Europe during this period. Known as the Justinian Plague, it ravaged populations, decimating economies and leaving entire regions depopulated.

If Britain was struck, its workshops and furnaces may have gone silent not because people forgot how to use them, but because there were too few people left to keep them running. The collapse, then, was biological as much as economic—a reminder of how fragile even the strongest industries can be in the face of pandemic.

Beyond the “Dark Age” Myth

These findings challenge one of the most persistent myths about early medieval Britain: that it was a time of total regression, when the achievements of Rome disappeared and society fell into barbarism. Instead, the sediment record paints a more complex picture. Industry continued. Skills were preserved. Communities adapted.

The term “Dark Age” has long carried the implication of backwardness, but Aldborough’s soil tells another story. Rather than a sudden descent into chaos, Britain experienced continuity, resilience, and eventual disruption caused by forces beyond its control.

Echoes Through Later History

The sediment core also reveals how Britain’s industrial heartbeat pulsed across later centuries. Metal production rose and fell with the tides of history. During Henry VIII’s reign, for instance, metal levels dropped when resources were stripped from monasteries during the Dissolution. Then, in Elizabeth I’s time, smelting surged again to fuel wars against Spain and France.

What the core provides is not just a snapshot but a moving picture—a continuous economic timeline showing how politics, religion, and war left chemical signatures in the earth itself.

A Revolutionary Insight

For Professor Christopher Loveluck of the University of Nottingham, the study’s lead author, the implications are profound. “The results offer a revolutionary new insight into the economic history of Britain,” he explains. “They contradict previous thought that all industrial-scale commodity production collapsed at the end of the Roman period.”

Instead, the story is one of adaptation, resilience, and sudden catastrophe—not of inevitable decline. The soil of Aldborough has shown that the past is never as simple as we assume, and that even in the silence of lost centuries, industry and innovation continued to shape lives.

Rethinking Our Own Legacies

What can we learn from this? On one level, it is a story about Britain’s ancient past, about Romans and their successors. But on another, it is about how human activity leaves marks that last for millennia. Just as the Romans’ furnaces left traces still detectable today, so too will our industries shape the soil of the future.

The Aldborough core is more than a record of metals; it is a reminder of continuity, resilience, and the enduring interplay between human societies and their environments. It shows us that the end of one empire does not mean the end of progress, and that history is often written not just in stone or parchment, but in the earth beneath our feet.

More information: Aldborough and the metals economy of northern England, c. AD 345–1700: a new post-Roman narrative. Antiquity (2025). doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10175