For thousands of years, ivory has captivated the human imagination. Smooth, pale, and lustrous, it was prized as both a rare material and a symbol of wealth. In the ancient world, ivory was not simply a substance—it was a marker of status, artistry, and power. The people of the southern Levant, situated between mighty empires and thriving coastal cities, were no strangers to its appeal.

A recent study led by Dr. Harel Shochat of the University of Haifa has cast new light on ivory’s journey into this region, tracing not just its artistic use but also its biological and geographical origins. Published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, this work blends archaeology, chemistry, and history to reveal a story of trade networks, cultural shifts, and human ingenuity. The results not only expand our understanding of ancient economies but also remind us that luxury and necessity often blur across time.

Ivory in the Late Bronze Age

In the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1600–1200 BCE), ivory was a luxury commodity par excellence. Artisans carved it into furniture components, cosmetic boxes, intricate decorative pieces, and votive items meant for ritual offerings. These ivories reflected the sophistication of the Canaanite city-states that dotted the Levant, many of which had fallen under the sway of Egypt’s New Kingdom.

In this period, ivory signaled elite consumption. To own an ivory-decorated chair or cosmetic box was to declare oneself part of a higher order of society—cosmopolitan, wealthy, and connected to international trade routes. The Egyptian presence in the region further reinforced this status: Egypt not only valued ivory but also played a key role in facilitating its movement from Africa into the Levant. Ivory was part of the texture of diplomacy, power, and display.

Shifting Realities in the Iron Age I

But history is rarely static. By the Iron Age I (ca. 1200–950 BCE), the great Canaanite city-states had collapsed, and Egypt had retreated from the region. This was an age of upheaval—marked by population shifts, the emergence of new groups like the Philistines, and the decline of established elites.

Ivory followed these social transformations. It disappeared from much of the northern Levant but lingered along the southern coastal areas, particularly in Phoenician and Philistine cities. Its function also changed. Instead of elite luxury objects, ivory was increasingly shaped into utilitarian items: spindles, whorls, combs—tools of daily life.

This democratization of ivory is striking. As Dr. Shochat explains, ivory “percolated further down in the social strata.” With no dominant elites to monopolize it, ivory found new life in the hands of merchants and ordinary people along the coast. A weaving kit carved from ivory was not just a tool—it was a subtle declaration of economic success, a way for merchants to showcase their status without the need for gilded thrones or monumental palaces.

Ivory’s Revival in Iron Age II

By the Iron Age II (ca. 950–600 BCE), the political landscape of the southern Levant had shifted once again. Territorial states such as Israel and Judah consolidated power, though by the 9th century BCE they had fallen into the orbit of the mighty Assyrian and Babylonian empires.

Ivory reemerged as a material of prestige. Its uses returned to decorative functions: furniture inlays, fittings, and ornaments once again adorned the homes of elites. Yet, in contrast to earlier eras, its trade networks showed remarkable resilience. Even as empires rose and fell, ivory continued to flow.

This resilience sets ivory apart from other commodities. Silver and copper trade waned during times of political collapse, but ivory endured. The networks that supplied it seem to have been more flexible, more personal, and more resistant to disruption.

Tracing the Origins of Ancient Ivory

Until recently, scholars studying Levantine ivory focused primarily on artistic style and historical references. But the question of origin—what animals the ivory came from, and where—remained largely unanswered. Dr. Shochat and his colleagues sought to change that.

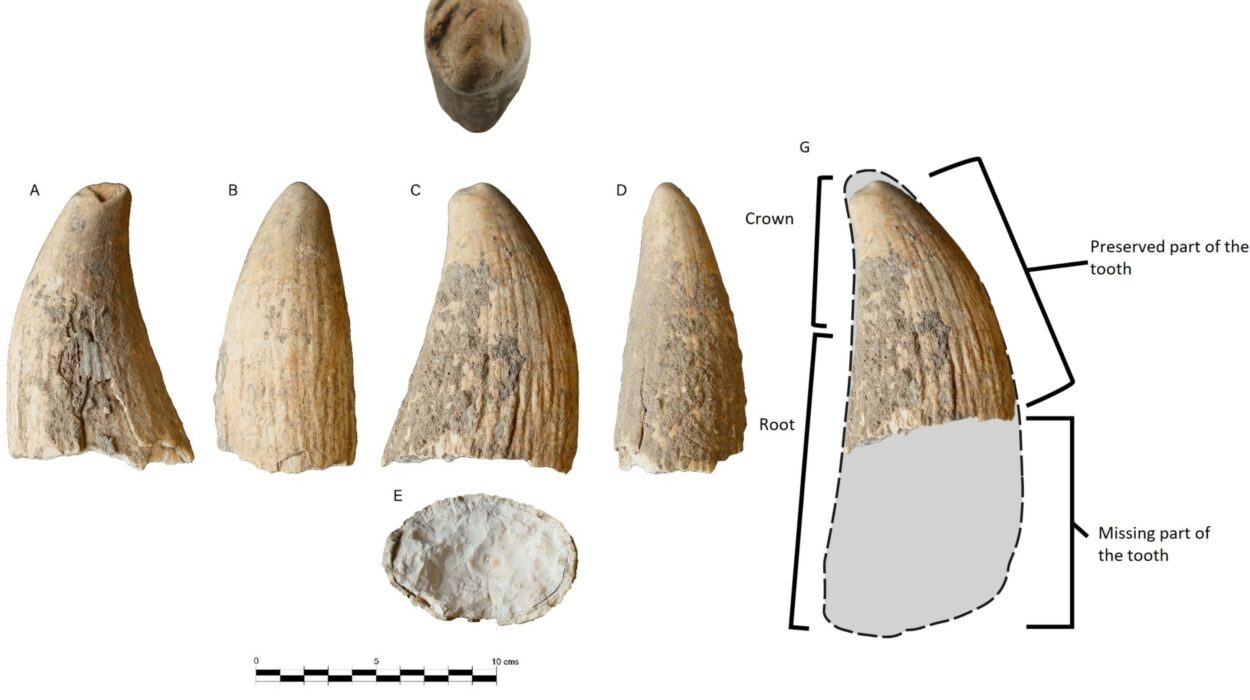

They analyzed 624 ivory artifacts using cutting-edge techniques: microscopy, mass spectrometry, and stable isotope analysis of carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, and nitrogen. These methods, often used today to track illegal poaching, provided direct biological and geographical evidence for the source of the ivory.

The results were illuminating. About 85% of the ivory came from elephants, nearly 15% from hippopotami, and a small fraction from boar tusks. Hippopotamus ivory was both local and imported, some originating in the Nile River basin. The elephant ivory, however, came exclusively from African elephants—not from Asian elephants, despite the potential for such ivory to have reached the Levant.

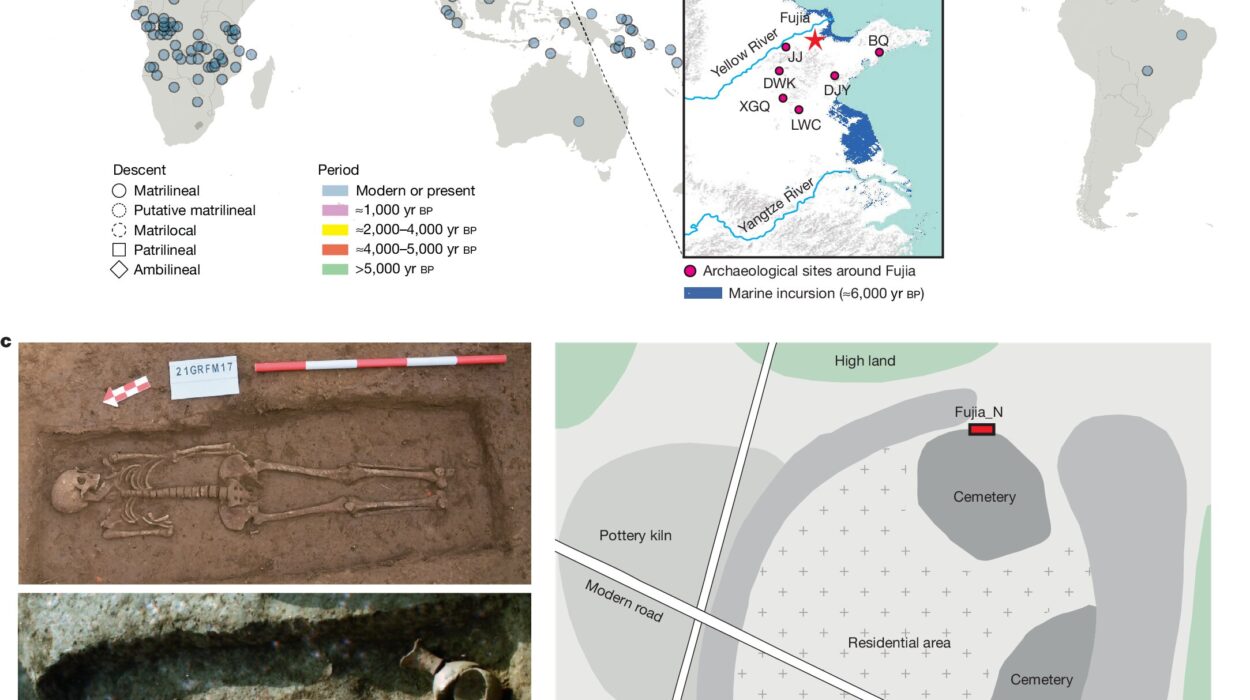

Even more specifically, the elephant tusks were traced to the sixth cataract of the Nile, south of modern Khartoum in Sudan. This finding implicates the Nubians as likely procurers of ivory, reshaping long-standing assumptions about the trade’s organization.

Rethinking Egypt’s Role

Traditionally, scholars assumed that Egypt tightly controlled the ivory trade, serving as the dominant hub that directed goods into the Levant. Egyptian sources often depicted Nubians as intermediaries, funneling ivory and other commodities northward.

Yet the new evidence paints a more complex picture. While Egypt certainly played a role in initiating exchange networks, the trade appears less centralized than previously believed. Instead of a rigid bureaucratic monopoly, the trade may have been characterized by permeability and individual enterprise.

This model helps explain why ivory trade persisted even when Egypt and the Levant experienced turmoil. Merchants, Nubians, and regional actors had incentives to maintain the networks, regardless of larger political collapses. In some cases, as Dr. Shochat suggests, Nubians may even have taken the lead in sustaining these flows once Egypt’s grip loosened.

The Social Life of Ivory

What emerges from this research is not just a story of trade but of people—how they valued ivory, used it, and wove it into their daily lives. In the Late Bronze Age, it was elite and exclusive. In the Iron Age I, it became utilitarian, signaling the aspirations of merchants and craftspeople. In the Iron Age II, it returned to elite decorative use, even under the shadow of imperial domination.

Ivory was never just ivory. It was a mirror of society, reflecting shifts in power, wealth, and identity. To pull out an ivory spindle in a coastal marketplace was to announce not only your craft but your success. To sit on an ivory-inlaid throne was to declare your authority. To carve votive offerings from ivory was to connect the material to the sacred.

Ivory’s Enduring Mystery

Even with this new study, questions remain. How exactly were trade routes organized? Who benefited most from the flow of ivory—states, merchants, or local communities? How did ivory intersect with other traded goods, like wine, oil, or textiles?

Dr. Shochat hopes that future research will expand the scope, applying the same analytical techniques to ivories from Cyprus, Syria, and beyond. By tracing the biological fingerprints of ancient ivory, archaeologists may uncover broader networks that linked the Mediterranean, Africa, and Asia in webs of exchange long before globalization as we know it.

Why This Matters Today

The story of ancient ivory is more than an academic puzzle. It reminds us that human societies have always been connected, that trade and exchange are as old as civilization itself. It shows how luxury items can shift in meaning—elitist in one age, utilitarian in another, resilient across centuries of upheaval.

It also illustrates the power of science to breathe life into history. By combining archaeology with chemistry and biology, researchers can reach beyond texts and artworks to touch the material reality of the past. The very tusks and teeth of animals long dead still speak, carrying the imprint of the rivers and soils where they once lived.

And in that sense, ivory is not just a relic of wealth or artistry. It is a witness—silent but enduring—to the movements of people, the rise and fall of kingdoms, and the unbroken thread of human ingenuity.

More information: Harel Shochat et al, A thousand years of Nubian supply of sub-Saharan ivory to the Southern Levant, ca. 1600–600 BCE, Journal of Archaeological Science (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2025.106366