Thirteen thousand years ago, the Earth stood at the threshold of transformation. Vast sheets of ice were retreating, the climate was warming, and early humans of the Clovis culture thrived across North America. Mammoths, mastodons, saber-toothed cats, and giant ground sloths roamed the landscape. But then, almost suddenly, something changed.

The great beasts vanished. The Clovis people, known for their masterful stone tools, disappeared from the archaeological record. And instead of continued warming, the planet was thrust back into a millennium of ice-age-like conditions. This sudden climatic reversal is called the Younger Dryas, and for decades, scientists have wrestled with one haunting question: what happened?

Among the most compelling—and controversial—answers is the Younger Dryas impact hypothesis. It suggests that fragments of a comet exploded above Earth, unleashing firestorms, shockwaves, and environmental collapse. Now, new evidence adds weight to this extraordinary scenario.

Evidence Written in Sand and Stone

A team led by James Kennett, an emeritus professor of Earth science at UC Santa Barbara, has reported striking new findings in PLOS One. At three iconic archaeological sites tied to the Clovis culture—Murray Springs in Arizona, Blackwater Draw in New Mexico, and Arlington Canyon on California’s Channel Islands—the researchers discovered grains of shocked quartz.

Shocked quartz is unlike ordinary sand. Under normal geological conditions, quartz crystals form neat, stable patterns. But when exposed to sudden, extreme pressures and temperatures—such as those generated in a cosmic explosion—the crystal lattice fractures in distinctive ways. These microscopic scars are signatures of catastrophe.

Using advanced techniques, including electron microscopy and cathodoluminescence, Kennett and colleagues confirmed that the quartz grains bore these telltale marks of trauma. Some even contained tiny veins of melted silica, evidence of temperatures that no volcano or human activity of the time could have produced.

The significance is profound: shocked quartz has long been considered one of the strongest indicators of extraterrestrial impact. And here, it was found alongside other cosmic fingerprints, including nanodiamonds, metallic spherules, meltglass, and layers of carbon-rich “black mat” sediments suggesting widespread burning.

When Fire Fell from the Sky

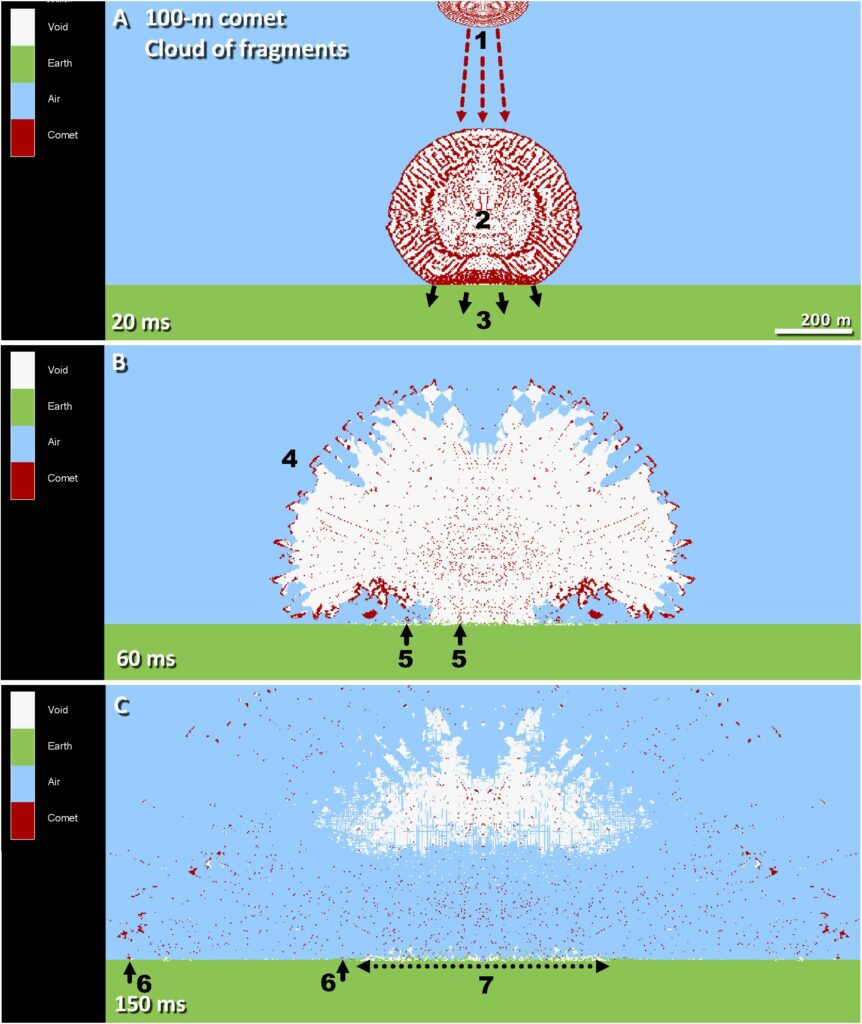

So what could have caused this destruction? Unlike the colossal asteroid that struck 65 million years ago and carved out the Chicxulub crater, the Younger Dryas event leaves behind no crater. That absence once cast doubt on the impact hypothesis. But Kennett’s team argues that the culprit was not a single massive asteroid, but rather a fragmented comet.

Such a comet, breaking apart in Earth’s atmosphere, would unleash airbursts—violent explosions above ground that deliver immense heat and shockwaves without ever striking the surface. These “touchdown airbursts” could vaporize landscapes, set forests ablaze, and blast shock patterns into quartz grains across vast regions.

To test this, the researchers used hydrocode modeling to simulate how low-altitude explosions might deform quartz. The results matched the diverse shock features found in their samples: some grains bore evidence of high-energy trauma, while others showed subtler fractures. This variation is precisely what would be expected from a fragmented comet scattering its fury over wide areas.

As Kennett vividly put it: “All hell broke loose.”

The Younger Dryas: A Sudden Deep Freeze

The timing of the explosions aligns eerily with the beginning of the Younger Dryas, roughly 12,800 years ago. For reasons still debated, the planet’s warming abruptly reversed. Glaciers surged again. Temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere plummeted.

One explanation is that the comet explosions injected soot, dust, and debris into the atmosphere, blocking sunlight and plunging Earth into an “impact winter.” Fires would have filled the skies with smoke, while shock-heated ice sheets released torrents of cold meltwater into the oceans, disrupting circulation patterns and deepening the chill.

The consequences would have been catastrophic for life. Plants struggled in the cold and darkness. Herbivores starved. Carnivores followed. And the Clovis culture—so reliant on megafauna—lost both its prey and its place in history.

The Death of Giants and a Culture’s Collapse

Mammoths and mastodons, icons of the Ice Age, dwindled and died. Saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, and giant ground sloths vanished as well. Across the Americas, more than 70% of large animal species went extinct.

For humans, the loss was cultural as well as biological. The Clovis people, once dominant, disappeared from the archaeological record. Their signature fluted spear points, masterworks of stone craftsmanship, ceased to be made. Some groups likely perished, while others adapted and evolved new ways of life.

The comet hypothesis suggests that this was not a slow decline but a rapid unraveling—triggered by cosmic violence.

Layers of Evidence

The discovery of shocked quartz is only the latest piece in a growing puzzle. For nearly two decades, Kennett and colleagues have documented impact proxies across North America and beyond. Among them are:

- The “black mat” layer, a dark sediment rich in soot and carbon, found at more than 50 sites.

- Nanodiamonds, tiny crystals formed under extreme pressures.

- Platinum and iridium anomalies, rare elements more common in comets and asteroids than in Earth’s crust.

- Meltglass and spherules, materials that only form when minerals are flash-melted and re-solidified at blistering temperatures.

Taken together, these proxies paint a consistent picture: something extraordinary, violent, and extraterrestrial scarred the planet at the onset of the Younger Dryas.

The Debate That Still Burns

Not all scientists are convinced. The Younger Dryas impact hypothesis remains controversial, with critics arguing that wildfires, volcanic activity, or human overhunting could explain the extinctions. Some question whether the impact proxies are truly cosmic in origin.

But the discovery of shocked quartz—long considered the “gold standard” of impact evidence—strengthens the case. While not definitive proof, it narrows the alternatives and underscores the possibility that Earth’s history has been shaped by forces from the sky more often than we realize.

Why It Matters Today

This story is not just about ancient mysteries. It is about our planet’s vulnerability. If a fragmented comet could transform the world 13,000 years ago, it could happen again. Unlike our Ice Age ancestors, however, we now have telescopes to track near-Earth objects, technologies to study them, and perhaps one day, the means to deflect them.

At the same time, the Younger Dryas event reminds us of nature’s fragility. Climate systems can shift suddenly. Ecosystems can collapse with terrifying speed. Human cultures can vanish in the wake of disaster. These lessons, written in layers of quartz and carbon, resonate in a world grappling with its own environmental challenges.

The Story Written in Quartz

The grains of shocked quartz found at Clovis sites are more than geological curiosities. They are tiny witnesses to a cataclysm, time capsules of a moment when fire rained from the sky and reshaped the destiny of life on Earth.

They remind us that history is not only made by slow, grinding forces but also by sudden, explosive events. They show that humanity’s story is inseparable from the story of the cosmos—that sometimes, the sky itself falls, and everything changes.

And so the mystery endures, a blend of science and wonder. Did a comet truly end the reign of mammoths and silence the Clovis hunters? The evidence grows, grain by grain, shard by shard, in the patient hands of those who dig and dream.

The truth, like the quartz itself, waits to be uncovered—etched into the Earth, illuminated by human curiosity, and forever tied to the night sky that still watches over us.

More information: James P. Kennett et al, Shocked quartz at the Younger Dryas onset (12.8 ka) supports cosmic airbursts/impacts contributing to North American megafaunal extinctions and collapse of the Clovis technocomplex, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0319840