For nearly 4,500 years, the dead lay in silence beneath the soil of Shandong’s coastal plains—bones woven into the earth, stories buried in time. But now, thanks to groundbreaking genetic research, their quiet resting place has found a voice. And it tells a tale that upends long-standing beliefs about how ancient societies were organized.

A Neolithic farming settlement in northeastern China, known as the Fujia site, has become the centerpiece of a remarkable new study published in Nature, revealing the first confirmed matrilineal society in prehistoric East Asia. The findings suggest that for more than ten generations, this small millet-farming community structured its society not around fathers, but around mothers.

This is not just a footnote in anthropology. It’s a revelation—one that rewrites our understanding of early human kinship and challenges the idea that patriarchal norms dominated ancient civilizations.

A Village Etched in Bone

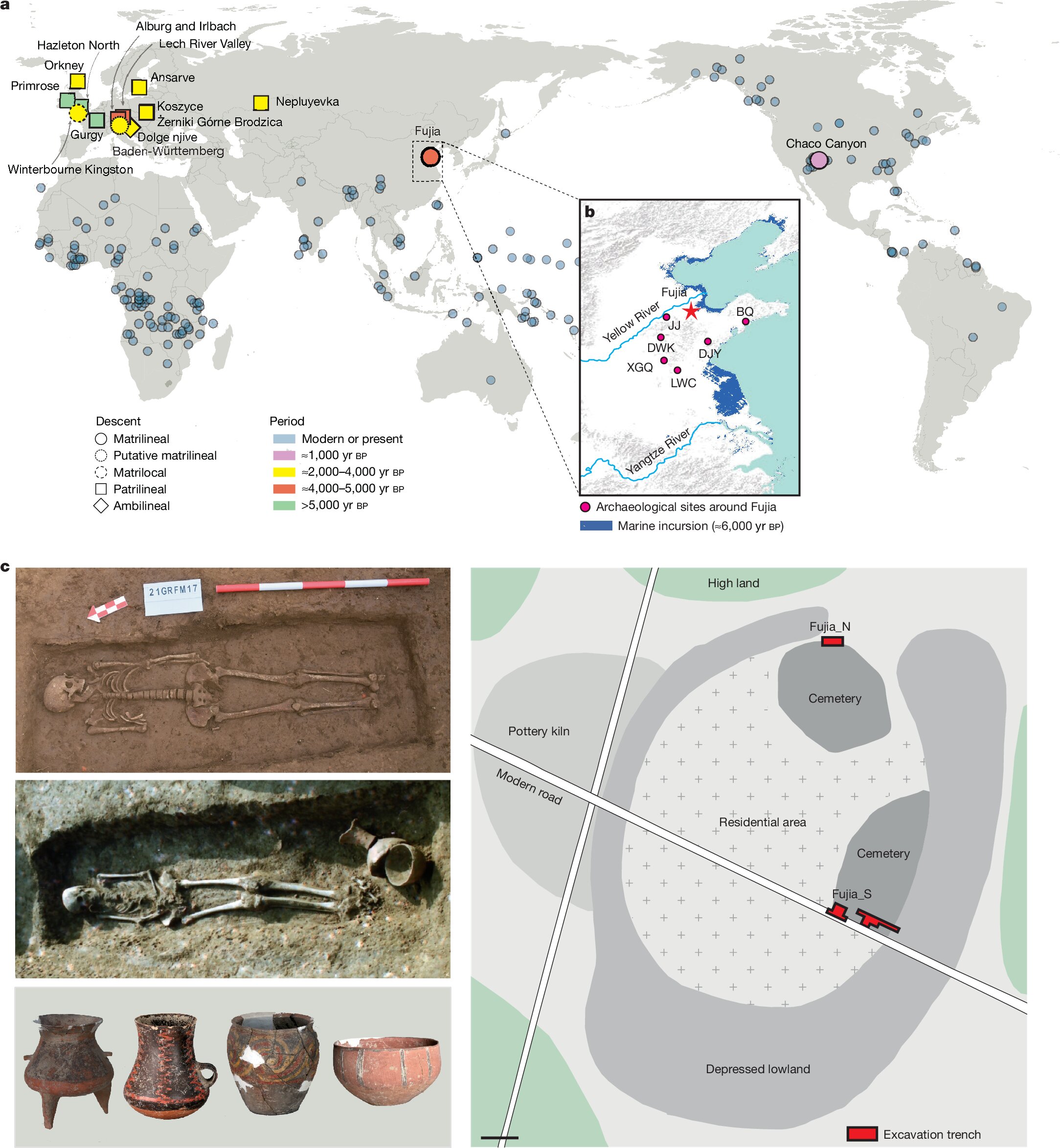

The Fujia site, located in Shandong province and dating from around 2750 to 2500 BCE, was once part of the late Dawenkou culture. Archaeologists from Peking University and international partners excavated more than 500 burials over three field seasons, uncovering two distinct cemeteries situated apart like silent echoes of long-forgotten family lines.

Within these cemeteries, researchers found more than just skeletons. They found a pattern. Of the 60 individuals whose ancient DNA was successfully sequenced, all 14 from the northern cemetery shared an identical mitochondrial DNA lineage—haplogroup M8a3. Meanwhile, 44 of the 46 from the southern cemetery carried haplogroup D5b1b. These mitochondrial signatures, passed down exclusively from mother to child, provided genetic fingerprints of maternal descent.

And yet, the Y-chromosome data—the paternal side of the family tree—told a different story. Male-line lineages varied widely, suggesting that paternal ties did not determine where people were buried. These men were not buried with their sons, nor women with their husbands. They were buried with their mothers’ people, adhering to the silent authority of the maternal line.

When Mothers Ruled the Hearth

For decades, archaeogenetics has painted a fairly uniform picture of Neolithic and Bronze Age Eurasian societies: patrilineal, patrilocal, and patriarchal. Men stayed in their natal communities, while women married out—migrating, often over long distances, to join their husbands’ families.

But Fujia flips that narrative on its head. Here, it was the women who stayed. Sons and daughters alike were buried with their maternal kin. Over centuries, these maternal clans remained remarkably intact—spanning at least ten generations, long enough for oral histories to fade, yet close enough for genetic memory to endure.

Even in cases where individuals were closely related across both cemeteries—say, first cousins whose mothers were sisters—each person was buried strictly in accordance with their specific maternal clan. The boundaries held. The structure persisted. The clans endured.

“This is one of the most striking examples of matrilineal social organization in the archaeological record,” says Dr. Fu Qiaomei, co-lead author and geneticist at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing. “We’re not just seeing a single family or a fluke. We’re seeing a whole community shaped around mothers and their descendants.”

Rooted Lives, Bounded Worlds

The study also incorporated isotopic data—chemical traces in bones and teeth that act like signatures of diet and mobility. The strontium isotopes revealed that almost no one had moved during their lifetime. The people of Fujia were born, raised, and buried within the same stretch of land. The carbon and nitrogen isotopes showed a diet rich in foxtail and broomcorn millet, along with meat from millet-fed pigs. Occasionally, freshwater or marine resources entered the mix, but life here was deeply local—geographically and socially.

This lack of mobility is important. It reinforces the idea that post-marital residence was not patrilocal. Women stayed close to their natal families, and their children were absorbed into the maternal lineage. Over time, the society became endogamous—not through cousin marriage, which was notably rare—but through repeated intermarriage within a closed, stable population of around 200 to 400 individuals.

The village was tight-knit. Its social fabric was taut with familiarity. It was a place where your identity was defined not by who your father was, but by the women who raised you—and the ancestral mothers who came before.

A Global Outlier—or Just the Beginning?

Globally, matrilineal societies are rare in the archaeological record. Only one other site—the elite burials at Chaco Canyon in what is now New Mexico—has produced definitive genomic evidence of a matrilineal descent system. Other possibilities have been floated, including Iron Age Britain and among ancient Celtic elites in southern Germany, but none have reached scientific consensus.

This makes Fujia extraordinary. It doesn’t just hint at matriliny—it proves it. And not in a palace or an elite dynasty, but in a modest farming village. A community of ordinary people whose social structure defied the dominant patriarchal molds of their time.

And that, say researchers, may be the most important takeaway. Fujia wasn’t a utopia or an anomaly. It may be a window into an entire tradition that has been overlooked because the tools to detect it—ancient DNA, isotope analysis, computational modeling—didn’t exist until now.

“The assumption has always been that patriliny was the default,” says Dr. Wen Shaoqing, an archaeologist at Peking University and senior author of the study. “But that assumption was based on incomplete evidence. What we’re learning is that the past was far more diverse than we imagined.”

The Lives Behind the Data

It’s easy, in a study so rich with data, to forget the human side of the story. But behind every mitochondrial haplogroup was a mother. A child. A family.

Imagine a girl born in Fujia 4,300 years ago. She learns to grind millet beside her grandmother. Her mother sings to her at night. She marries a man from down the path—but when she dies, she is buried not with him, but with her mother’s people, under the same earth as the women who shaped her. Her children, too, will return to this ground, forming a long, unbroken chain that stretches across centuries.

These aren’t just bones. They are echoes. And for the first time, we can hear them clearly.

Rethinking the Origins of Inequality

One of the more subtle implications of the Fujia study is the challenge it poses to long-held theories about the origins of social inequality. Matrilineal societies today, such as the Mosuo of southwest China or the Minangkabau of Indonesia, often exhibit more egalitarian gender norms and less hierarchical wealth distribution than their patrilineal counterparts.

Fujia, with its low residential mobility, limited wealth accumulation, and stable kinship patterns, may have been similarly structured. There were no grand tombs or towering monuments here—no obvious signs of powerful elites or social stratification.

Instead, what researchers found was continuity. Equality. Balance.

“The matrilineal organization at Fujia may have supported a more horizontal social structure,” says Dr. Fu. “That doesn’t mean it was a paradise. But it suggests that alternative models of community life—less dominated by wealth, war, or patriarchal control—were viable, and perhaps even common, in prehistory.”

A New Map for Prehistory

The discovery at Fujia does more than shed light on one Neolithic village. It offers a roadmap for future research. By combining ancient DNA, isotopic chemistry, burial analysis, and statistical modeling, archaeologists now have a powerful toolkit for uncovering hidden social structures.

This integrative approach could soon be applied to other sites across East Asia—and perhaps reveal that Fujia was not alone.

“This is just the beginning,” says Dr. Wen. “There may be many more matrilineal communities waiting to be rediscovered.”

In the end, the story of Fujia is a reminder that history is never set in stone. Sometimes it lies in the soil—waiting patiently, quietly, until science is ready to listen.

Reference: Jincheng Wang et al, Ancient DNA reveals a two-clanned matrilineal community in Neolithic China, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09103-x