In the heart of western Iran, where the winds sweep over the low hills of Ilam Province and the earth has kept its secrets for millennia, two archaeologists have unearthed a haunting relic of the distant past. At a sprawling ancient cemetery known as Chega Sofla, among bones long forgotten and tombs of brick worn by time, researchers discovered the skull of a young girl—delicately deformed and fatally fractured. Her story, buried for over six thousand years, is now being told for the first time.

A Skull in the Dust

For more than a decade, excavations at Chega Sofla have peeled back the layers of a prehistoric settlement, one grave at a time. Single burials, family plots, and communal graves whisper of customs lost to time. Among them, a peculiar pattern has emerged—some skulls, particularly those of women and girls, bear the unmistakable signs of cranial modification.

It was in this context that Dr. Mahdi Alirezazadeh and Dr. Hamed Vahdati Nasab, seasoned archaeologists and osteoarchaeologists with a deep understanding of Iran’s ancient cultures, uncovered a skull that stopped them in their tracks.

“She was young,” Dr. Alirezazadeh recalls. “No older than twenty. And her head had been shaped—deliberately, systematically—into a smooth, cone-like form.”

Such modifications, often achieved by tightly binding a child’s head with cloth or boards during the earliest years of life, were not uncommon across ancient cultures. From the Mayans of Central America to the Huns of Eurasia, cranial shaping was a symbol—of beauty, of status, of identity. In Chega Sofla, it may have marked this girl as someone of significance.

A Dangerous Beauty

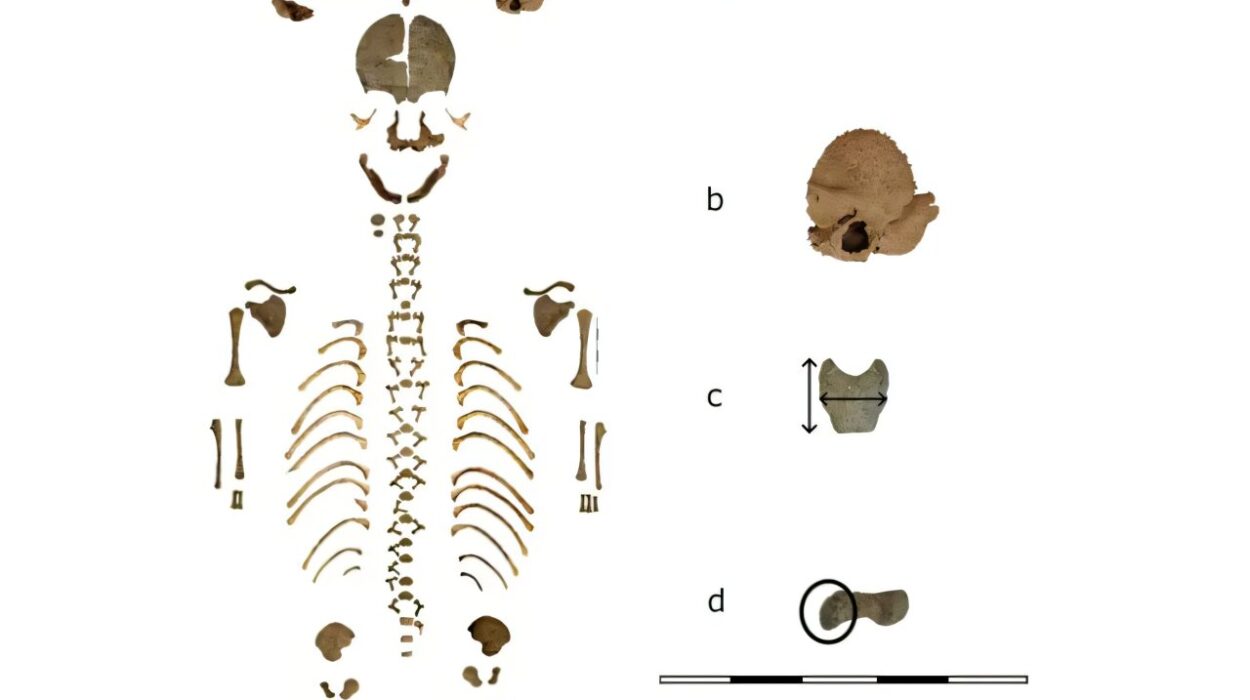

The skull was fragile but well-preserved. To understand the internal structure without damaging it, the team turned to CT scanning, creating a digital model of the ancient bone. What they found was both fascinating and heartbreaking.

The girl’s skull was unusually thin. The long years of pressure from head binding had not just shaped her appearance—it had altered the biology of her skull. It was less robust than normal, leaving her more vulnerable to trauma. And trauma, it seems, is what claimed her life.

A fracture stretched from the front of her skull all the way to the back. Clean, devastating, and fatal. There were no signs of healing, indicating she died shortly after the blow was delivered. The researchers believe the injury was caused by a strike from a broad-edged object—possibly a club or axe-like weapon.

Despite the violence of her end, there was no penetration of the skull. But the force of the impact, combined with the skull’s reduced thickness, was enough to send a shockwave straight to her brain.

An Individual in the Crowd

The girl’s skeleton has not yet been fully recovered. The grave site is densely packed, a woven mosaic of intermingled remains. But even this single skull opens a vivid window into a lost world.

Who was she? Was she a daughter of nobility, marked for honor through cranial modification? Or perhaps part of a cultural elite whose appearance defined her place in society? Was her death the result of war, domestic violence, or ritual punishment?

The archaeological record is often generous with artifacts and stingy with names. We may never know her story in full. But her skull, shaped by tradition and shattered by violence, speaks volumes.

Shaped by Culture, Silenced by Violence

The practice of cranial modification has puzzled scientists for decades. It has no known medical benefit. But across continents and centuries, humans have been drawn to the idea of shaping the body to reflect social ideals. In many ancient societies, especially those with stratified social systems, cranial modification served as a physical mark of status, ethnicity, or even spiritual elevation.

At Chega Sofla, the prevalence of modified skulls—especially among females—suggests that girls were often the bearers of this tradition. Whether for beauty or belonging, they were shaped by the hands of others from infancy.

But modification came with risks. As this case tragically illustrates, thinning of the cranial bones made modified individuals more susceptible to fatal head trauma. While it’s impossible to say how often this happened, the evidence now shows at least one such death—sudden, violent, and final.

A Brick Tomb and an Ancient World

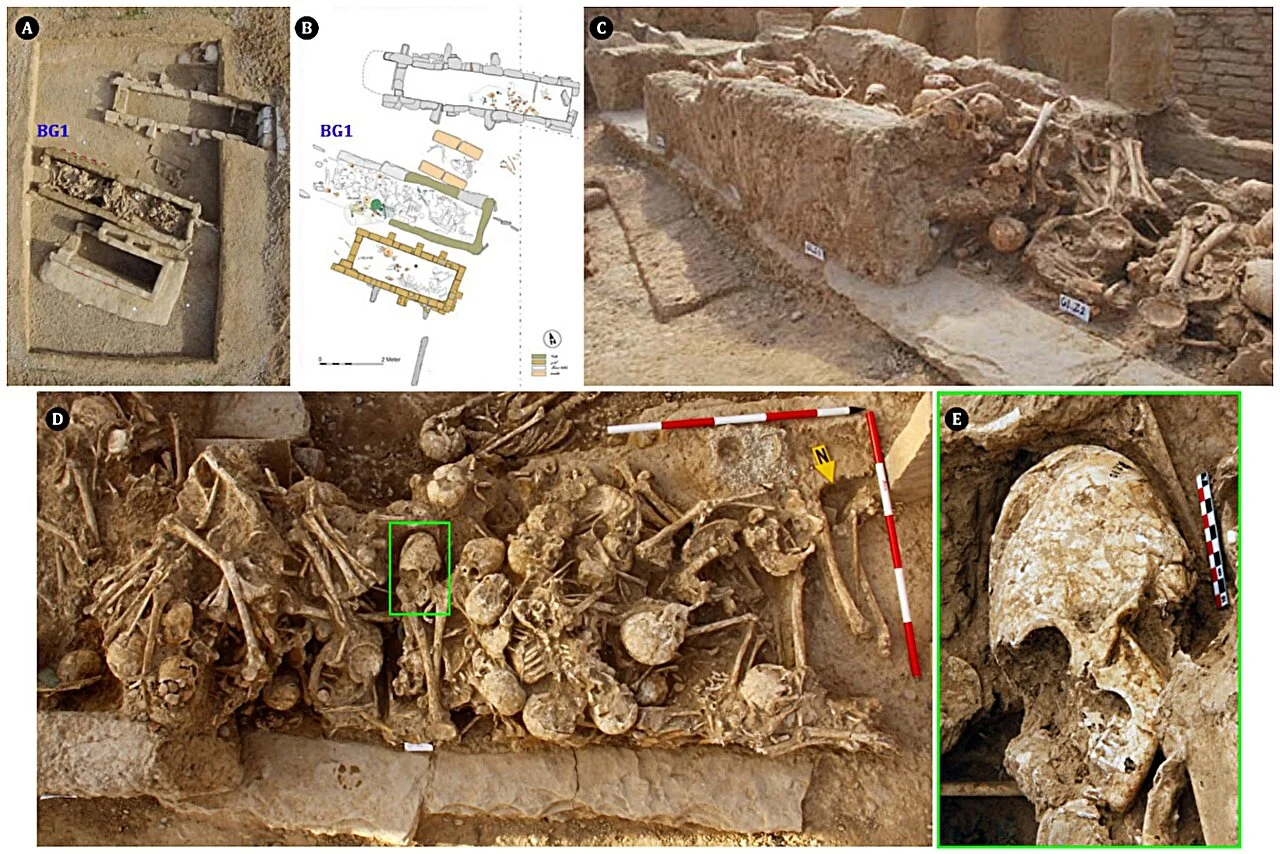

Chega Sofla is more than a graveyard. It is an archaeological palimpsest, revealing layer after layer of early urban life in western Iran. Among its many surprises is the discovery of what is now considered the oldest-known tomb constructed entirely of brick—an architectural innovation in a time when most of the world was still building with mud and stone.

This tomb, though separate from the young girl’s burial, underscores the significance of the site. Chega Sofla was not a mere village. It was a place where traditions ran deep, where innovation mingled with ritual, and where the dead were laid to rest with intention.

The girl with the cone-shaped skull was one of many. But her death—recorded in the cracks of her bones—gives voice to a time when societal expectations could shape not just lives, but bodies, and when the line between honor and harm was as thin as the skull of a child.

The Echo of an Ancient Life

As scientists piece together the past, stories like hers bring a human face to history. Her bones, silent for over six millennia, speak now with clarity and poignancy. They remind us that even in the ancient world, children were loved, shaped, and sometimes lost to violence. That cultures, however distant, still grappled with identity, tradition, and tragedy.

“She lived in a time long before writing, before cities as we know them,” said Dr. Vahdati Nasab. “But she mattered. Her life—and her death—deserve to be remembered.”

And now, she is.

Reference: Mahdi Alirezazadeh et al, A Young Woman From the Fifth Millennium BCE in Chega Sofla Cemetery With a Modified and Hinge Fractured Cranium, Southwestern Iran, International Journal of Osteoarchaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1002/oa.3415