High in the Paltau valley of northeastern Uzbekistan, nestled at the southwestern edge of the Talassky Alatau mountains, lies the Obi-Rakhmat rock shelter. For decades, archaeologists have carefully peeled back its layers of sediment, each one preserving traces of ancient human life. The shelter is a time capsule spanning tens of thousands of years, with deposits ranging from 90,000 to 40,000 years ago.

Now, researchers from the Université de Bordeaux and the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography in Novosibirsk report astonishing evidence: stone points from the deepest layers of Obi-Rakhmat—around 80,000 years old—may represent some of the earliest arrowheads ever made.

Their study, published in PLOS ONE, sheds new light on the origins of projectile technology and the sophisticated hunting strategies of our ancient relatives.

Why Projectile Weapons Mattered in Human Evolution

The invention of hunting weapons marked a turning point in human history. For members of the genus Homo, the ability to reliably kill game from a distance meant more than just securing food. It shaped diet, social cooperation, cognition, and even the way humans structured their lives.

Spear points appear widely in the archaeological record, but smaller, lighter weapons such as arrows have often been overlooked in research on the Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition. Yet arrows represent a leap in complexity: they require not just sharp tips but aerodynamic shafts, knowledge of propulsion, and coordinated hunting tactics.

If confirmed, the evidence at Obi-Rakhmat would push back the earliest known use of arrow-like projectiles by tens of thousands of years.

Sorting Stones into Weapons

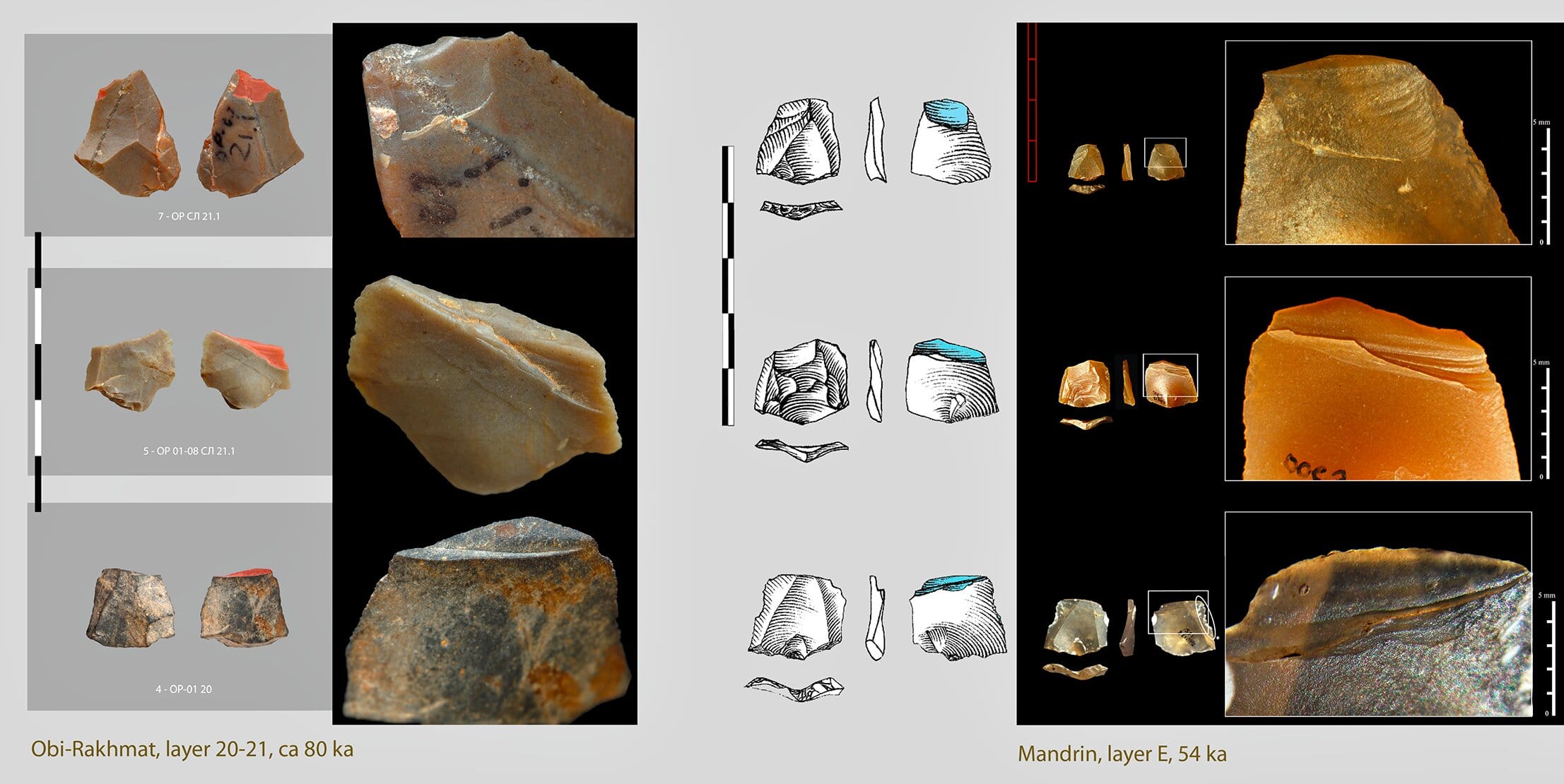

To test the possibility, researchers designed a careful traceological study of lithic material from layers 20–21 of the rock shelter, dated to about 80,000 years ago.

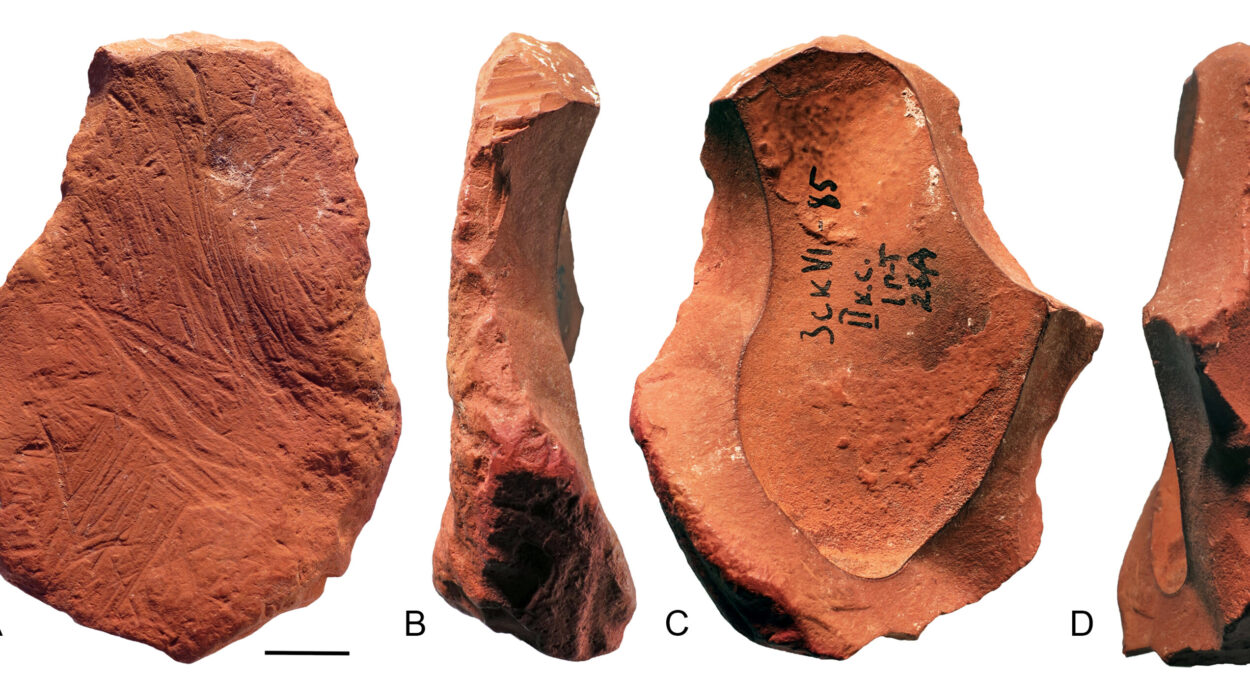

From nearly 400 pieces of stone debris, they identified 20 potential weapon armatures. These included large retouched points, slender triangular “micropoints,” and delicate bladelets. Each was examined for microscopic traces of impact damage, such as fractures or stress lines, using high-powered reflective optical microscopy.

To go beyond observation, the team conducted experiments. They knapped new points from local silicified limestone, mounted them onto wooden shafts, and fired them from a 36-pound laminated bow at a suspended ungulate carcass. This unusual test provided a direct way to compare ancient damage with fresh impact signatures.

The Three Weapon Classes

The study isolated three distinct categories of projectiles:

- Large retouched points: Broader, heavier pieces (up to 41 mm wide) that fractured on impact. These were likely used as spear tips, powerful but designed for close-range hunting.

- Micropoints: Small triangular flakes, some only 1–2 cm in size, weighing little more than a gram. Several bore fractures and microscopic impact traces identical to those from the experimental arrows. Their lightweight, aerodynamic form made them unsuitable for spears, but perfectly compatible with arrow-like shafts.

- Bladelets: Slender fragments sometimes showing crushing on the edges, suggesting they were inserted laterally into composite weapons.

The presence of these three types in the same stratigraphic layers hints at a sophisticated, varied hunting toolkit.

Rethinking the Middle Paleolithic

What makes Obi-Rakhmat remarkable is the age of these finds. At ~80,000 years old, the micropoints predate the traditionally accepted timeline for bow-and-arrow technology by tens of millennia.

Most scholars place the appearance of arrows in the Late Pleistocene, around 50,000 years ago, often associated with the spread of Homo sapiens into Africa and Eurasia. But if the Obi-Rakhmat pieces were indeed used as arrowheads, this suggests that the conceptual leap toward lightweight projectiles may have begun much earlier, within a Middle Paleolithic cultural framework.

It also implies that the mental capacity to design, mount, and use such weapons was already within reach of early Eurasian hominins—whether Neanderthals, Denisovans, or early modern humans inhabiting the region.

The Bow, the Arrow, and the Mind

The bow itself leaves no trace in the archaeological record; wood, sinew, and fiber rarely survive the millennia. But the tiny stone tips at Obi-Rakhmat speak volumes about human creativity. To make a functional arrow, one must not only craft a sharp point but also balance it with a shaft, stabilize it with fletching, and learn the skill of propulsion. This requires planning, foresight, and a deep understanding of materials.

Such complexity suggests that by 80,000 years ago, humans—or their close relatives—were already experimenting with technological systems that demanded cooperation and teaching.

What Comes Next

The researchers caution that more work is needed. Larger samples must be studied across the full stratigraphy of Obi-Rakhmat to confirm whether these lightweight points persisted through time and whether they were consistently used as projectiles.

Still, the initial findings are groundbreaking. They challenge assumptions about when and where complex hunting technologies arose and highlight Central Asia as a key region in human prehistory.

A Window into Human Ingenuity

The small triangular flakes from Obi-Rakhmat may seem insignificant, but they carry with them an extraordinary story. They suggest that nearly 80,000 years ago, in the shadow of the Tien Shan mountains, ancient hunters were already experimenting with weapons that extended their reach, sharpened their survival, and hinted at the imaginative leaps that would one day define our species.

As the authors of the study put it, the evidence for arrow-like points in such an early context invites us to rethink not only human technology but the very pathways of human thought.