The story begins in silence. Nearly two thousand years ago, the volcanic fury of Mount Vesuvius froze a Roman construction site in Pompeii mid-stride, preserving raw materials, half-finished walls, and the physical traces of workers who never returned. When MIT Associate Professor Admir Masic stepped into that space for the first time, the shock of recognition washed over him so strongly that tears filled his eyes. As he later recalled, “I expected to see Roman workers walking between the piles with their tools. It was so vivid, you felt like you were transported in time. So yes, I got emotional looking at a pile of dirt.”

What lay before him was not just an archaeological discovery. It was the missing chapter in a centuries-long mystery about how Roman concrete survived storms, quakes, and time itself. It was also the key to resolving a tension between modern science and the oldest architectural book in existence.

The Ancient Recipe and the Modern Doubt

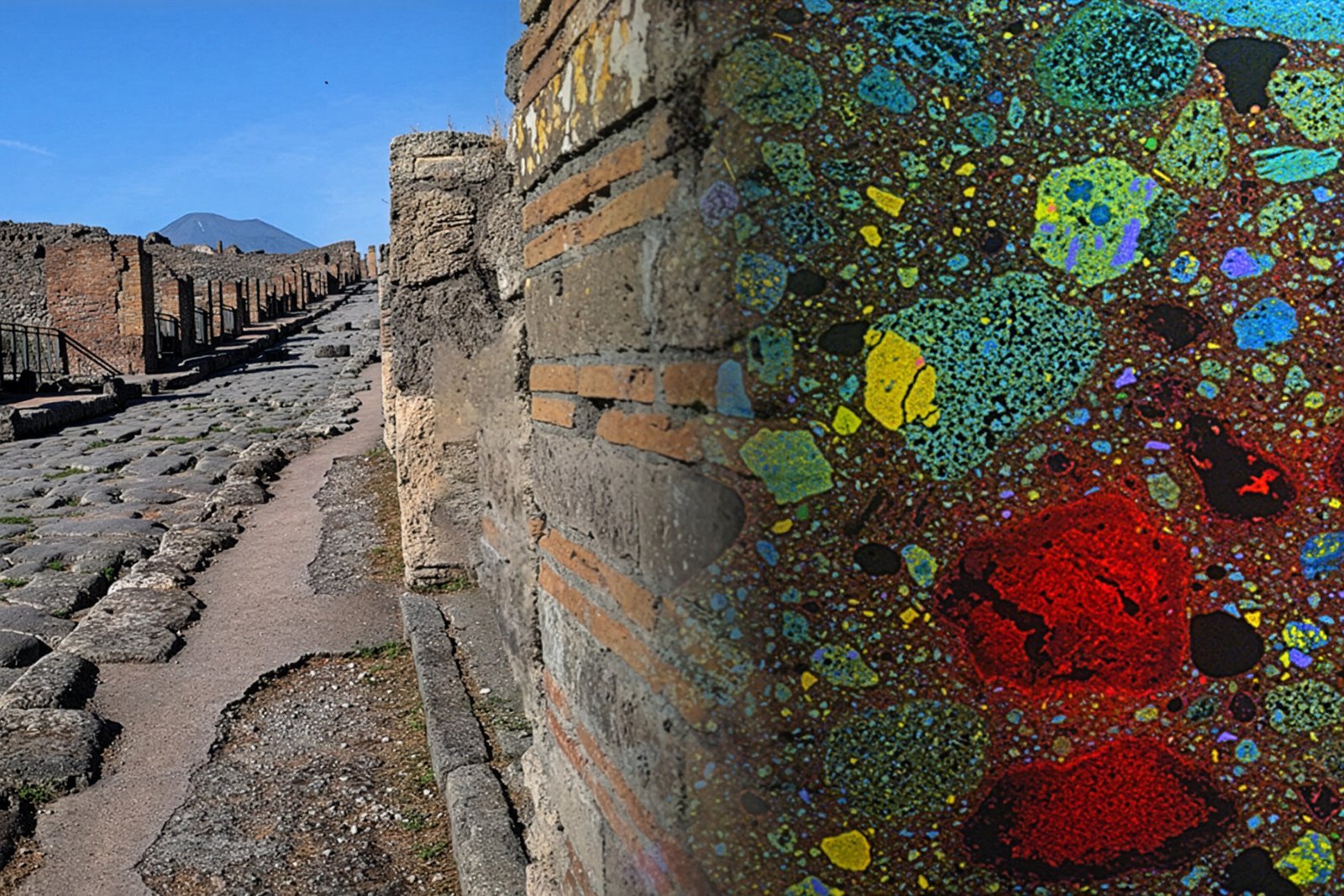

Concrete was the skeleton of the Roman empire. Its aqueducts, harbors, and temples still stand today, mocking the short lifespans of modern construction. In 2023, Masic and his collaborators identified the process they believed gave Roman concrete its astounding longevity. The trick, they reported, was “hot-mixing.” Romans took lime fragments, blended them with volcanic ash and other dry materials, and only then added water. This step produced heat—enough to trap reactive lime inside the mixture as tiny white clasts.

These lime clasts were the secret agents of self-repair. When cracks formed, the reactive fragments dissolved and filled the gaps, healing the concrete from within.

There was only one problem. The ancient Roman architect Vitruvius described something different. In “De architectura,” the first known book on architectural theory, he said the Romans added water to lime first, creating a paste before mixing it with other ingredients. Masic admitted, “Having a lot of respect for Vitruvius, it was difficult to suggest that his description may be inaccurate. The writings of Vitruvius played a critical role in stimulating my interest in ancient Roman architecture, and the results from my research contradicted these important historical texts.”

The contradiction hung in the air like an unresolved chord. Had the scientists misinterpreted the evidence? Or had Vitruvius—a meticulous observer—left something unsaid?

Pompeii held the answer.

A Time Capsule Buried in Ash

Archaeologists recently uncovered a perfectly preserved construction site in Pompeii, still dusted with the remains of 79 C.E. raw material piles, tools, and walls in different stages of completion. For Masic, it was as if the Romans themselves had laid out a laboratory for the future.

“We were blessed to be able to open this time capsule of a construction site and find piles of material ready to be used for the wall,” he said.

The team collected samples from every part of the site: the dry material piles, the partially constructed wall, fully built structural walls, and later mortar repairs. It was the clearest sequence of Roman concrete preparation ever found.

The evidence was unambiguous. Hot-mixing was real. It was deliberate. And it was everywhere.

Not only did finished concrete contain the lime clasts Masic had described earlier, but the raw dry piles contained intact fragments of quicklime—an unmistakable clue. The Romans were mixing lime and volcanic ash dry first, exactly as Masic’s data had suggested, and only later adding water to trigger the heat-rich reaction.

The Chemistry Hidden in the Ash

To untangle exactly how this ancient concrete formed and evolved, Masic’s team turned to stable isotope tools developed with Associate Professor Kristin Bergmann. These tools allowed them to follow the carbonation reactions over time, revealing a signature unique to hot-mixed lime.

“Through these stable isotope studies, we could follow these critical carbonation reactions over time, allowing us to distinguish hot-mixed lime from the slaked lime originally described by Vitruvius,” Masic explained.

He summarized the true Roman method: “These results revealed that the Romans prepared their binding material by taking calcined limestone (quicklime), grinding them to a certain size, mixing it dry with volcanic ash, and then eventually adding water to create a cementing matrix.”

The volcanic ash itself told another story. The researchers found pumice particles filled with reactive minerals. Over centuries, these pumice grains continued to react with the surrounding pore solution, slowly forming new mineral deposits that strengthened the concrete even further. The material did not simply harden once. It evolved. It adapted. It lived.

A Bridge Between Past and Future

For Masic, the discovery was more than a historical revelation. It was personal, scientific, and full of possibility.

“There is the historic importance of this material, and then there is the scientific and technological importance of understanding it,” he said. “This material can heal itself over thousands of years, it is reactive, and it is highly dynamic. It has survived earthquakes and volcanoes. It has endured under the sea and survived degradation from the elements.”

He is quick to emphasize that modern builders should not copy Roman concrete entirely. Instead, the goal is to translate its lessons. “We don’t want to completely copy Roman concrete today. We just want to translate a few sentences from this book of knowledge into our modern construction practices.”

Masic believes the Romans may not have contradicted Vitruvius at all. In fact, Vitruvius mentioned latent heat during mixing—an echo of the hot-mixing process. Perhaps his words were simply misunderstood.

Meanwhile, Masic is already applying ancient wisdom to modern technology. His company, DMAT, is working to create new concretes with self-regenerating properties. As he puts it, “This is relevant because Roman cement is durable, it heals itself, and it’s a dynamic system. The way these pores in volcanic ingredients can be filled through recrystallization is a dream process we want to translate into our modern materials. We want materials that regenerate themselves.”

Why This Discovery Matters

The rediscovery of hot-mixed Roman concrete is not just a story of ruins or ancient craft. It is a breakthrough with immediate implications for our world today.

Modern concrete—one of the most widely used materials on Earth—cracks, crumbles, and demands constant repair. It contributes significantly to global carbon emissions. Reimagining it through the lens of Roman innovation could transform everything from urban infrastructure to climate impacts.

By understanding how a material “can heal itself over thousands of years,” Masic and his collaborators illuminate a path toward stronger, more resilient, and more sustainable building practices.

In the buried construction site of Pompeii, the Romans left behind a message written not in words, but in stone. Today, we are finally learning to read it.

More information: Admir Masic, An unfinished Pompeian construction site reveals ancient Roman building technology, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-66634-7. www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-66634-7