In the rolling hills of the Jezreel Valley, just 15 kilometers from the bustling ancient city of Tel Megiddo, an archaeological site called Horvat Tevet has revealed a stunning discovery that challenges long-held assumptions about the Neo-Assyrian Empire’s control over the region. It’s a discovery that combines the richness of ancient trade networks, the customs of the Iron Age, and the lingering question of how the empire truly viewed its territories.

The burial assemblage uncovered at Horvat Tevet dates back to the 7th century BCE, an era when the Neo-Assyrian Empire was asserting its power over vast swaths of the ancient world. At the heart of this discovery is a cremation burial—a rare and unusual practice for the region at the time. This burial, found in a poorly preserved state but still brimming with valuable artifacts, tells a story of a person whose life and death were intimately connected to long-distance trade and the shifting political landscape of the Southern Levant.

The Buried Remains: An Unexpected Ritual

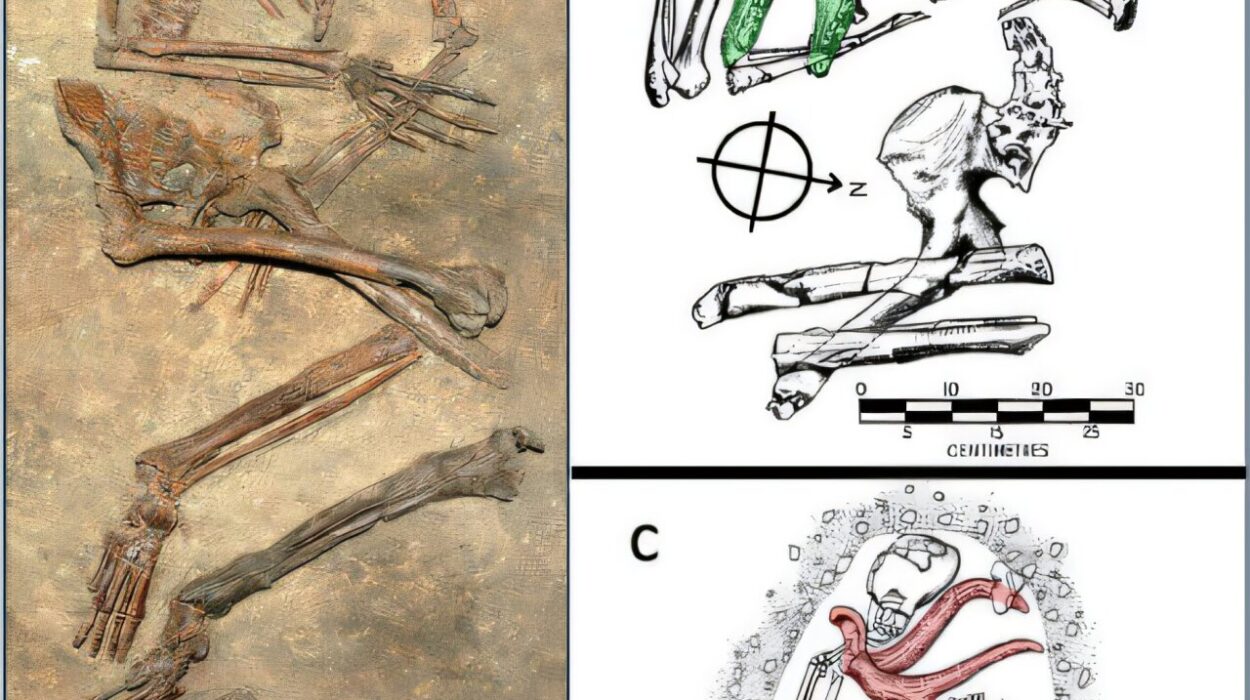

The burial site at Horvat Tevet consisted of two pits. One contained the articulated remains of an adult, while the other was a cremation burial—a burial practice not commonly seen in the interior regions of the Southern Levant during the Iron IIC period. Most cremation burials from this time were typically found in coastal Phoenician areas. The rarity of this practice inland, especially in the Jezreel Valley, raised the first eyebrow of the researchers.

Dr. Omer Sergi, a key author of the study, explained that the cremated remains themselves didn’t yield much osteological information. “We have no additional osteological information, nor can we do any analysis (like isotopes or other), as due to the local conditions, we only have a small fragment of a finger bone.” Despite this limitation, it was clear that this was an important burial—its significance lay in what surrounded the remains: a collection of artifacts that spoke volumes about the deceased’s identity and connections.

Unveiling the Richness of the Burial

The cremation burial was housed in a pit adorned with three urns, each of which held different objects. Urn 1014/2 was the least adorned, containing only modest items such as broken bowl fragments, a faience amulet, and a thickened, folded rim that may have once served as a lid. In contrast, the other two urns—Urn 1014/1 and Urn 1014/3—contained a stunning array of artifacts, some of which were unmistakable signs of the deceased’s elite status.

Urn 1014/1, an amphoroid krater decorated with colored bands, contained three juglets, two bottles, a faience alabastron (a glazed ceramic vessel), a cylindrical seal, a stone weight, and several pieces of jewelry—seven bronze objects, including fibulae (ancient pins) and earrings, as well as 55 beads. The richness of these artifacts immediately stood out.

Urn 1014/3, though slightly less embellished, still contained valuable items: two faience amulets, a stone pendant, and 36 beads. It was clear that this burial was not a simple affair—it was a message, not only about the deceased’s importance but also about their connections to a broader world beyond the local community.

The Glimpse into Assyrian Connections

The most remarkable aspect of this burial lies in the specific items that point directly to the Neo-Assyrian Empire’s influence over the region. The inclusion of a glazed Assyrian bottle, decorated with lotus petals in green, yellow, and white, was particularly striking. Such bottles were typically found in royal Assyrian burial chambers, making it clear that this item had traveled a long distance to end up in the Jezreel Valley. The bottle was more than just an ornament—it symbolized the deceased’s connection to the empire and its luxury trade goods.

Further reinforcing this connection were a stone weight and a Neo-Assyrian cylinder seal, both of which are commonly associated with professional tradespeople such as blacksmiths, merchants, or officials. These items indicated that the deceased may have held a significant role in Assyrian-controlled trade networks, possibly as a merchant or even as an official.

The alabastron, another notable artifact, featured an image of flying ducks among papyrus plants—a motif common in Mediterranean cultures, especially in the Aegean Sea region. This vessel highlighted the far-reaching connections of the deceased, suggesting that they were part of an elite network that spanned across seas and cultures.

A New Perspective on Neo-Assyrian Rule

For years, scholars have argued that the Neo-Assyrian Empire treated regions like the Jezreel Valley as little more than sources of raw materials, exploiting the land while neglecting its development. The sparse evidence of wealth in the area during the Iron IIC period seemed to support this view. But the burial at Horvat Tevet challenges this assumption.

The exceptional richness of the burial suggests that the Neo-Assyrians saw this region as more than just an agricultural resource. By burying an individual of high social standing—possibly a merchant, an official, or both—with such valuable artifacts, the empire could have been asserting its control over the region in a very symbolic way. The luxury items associated with the deceased were not merely personal possessions; they were part of a larger narrative of imperial influence and prestige.

The burial may have been strategically located at Horvat Tevet, a site once used by various ancient empires, to further underscore the connection between rural hinterlands and the urban centers under Assyrian control. The person buried here may have been transported from nearby Tel Megiddo, a major urban hub, to underscore the political and administrative links between the countryside and the Assyrian imperial apparatus.

Why This Matters

This discovery at Horvat Tevet adds a new layer of complexity to our understanding of the Neo-Assyrian Empire’s rule over the Southern Levant. Far from neglecting the region, as previously believed, the Assyrians may have been strategically maintaining long-term control, using wealth and burial practices to solidify their grip on the fertile and politically significant Jezreel Valley.

For historians and archaeologists, the Horvat Tevet burial site offers a fascinating glimpse into the lives of those who lived under Assyrian rule—individuals whose roles in trade, governance, and cultural exchange may have been far more important than previously imagined. The artifacts found here are not just relics; they are symbols of an empire that extended its influence in ways that were not always visible on the surface.

As we continue to unearth more about the past, the story of Horvat Tevet reminds us that history is full of surprises. What we once thought we understood about the relationship between ancient empires and their territories is now being rewritten, one discovery at a time.

More information: Omer Peleg et al, A Unique Assemblage of Cremation Burial from Ḥorvat Tevet and Assyrian Imperial Rule in the Jezreel Valley, Tel Aviv (2025). DOI: 10.1080/03344355.2025.2550116