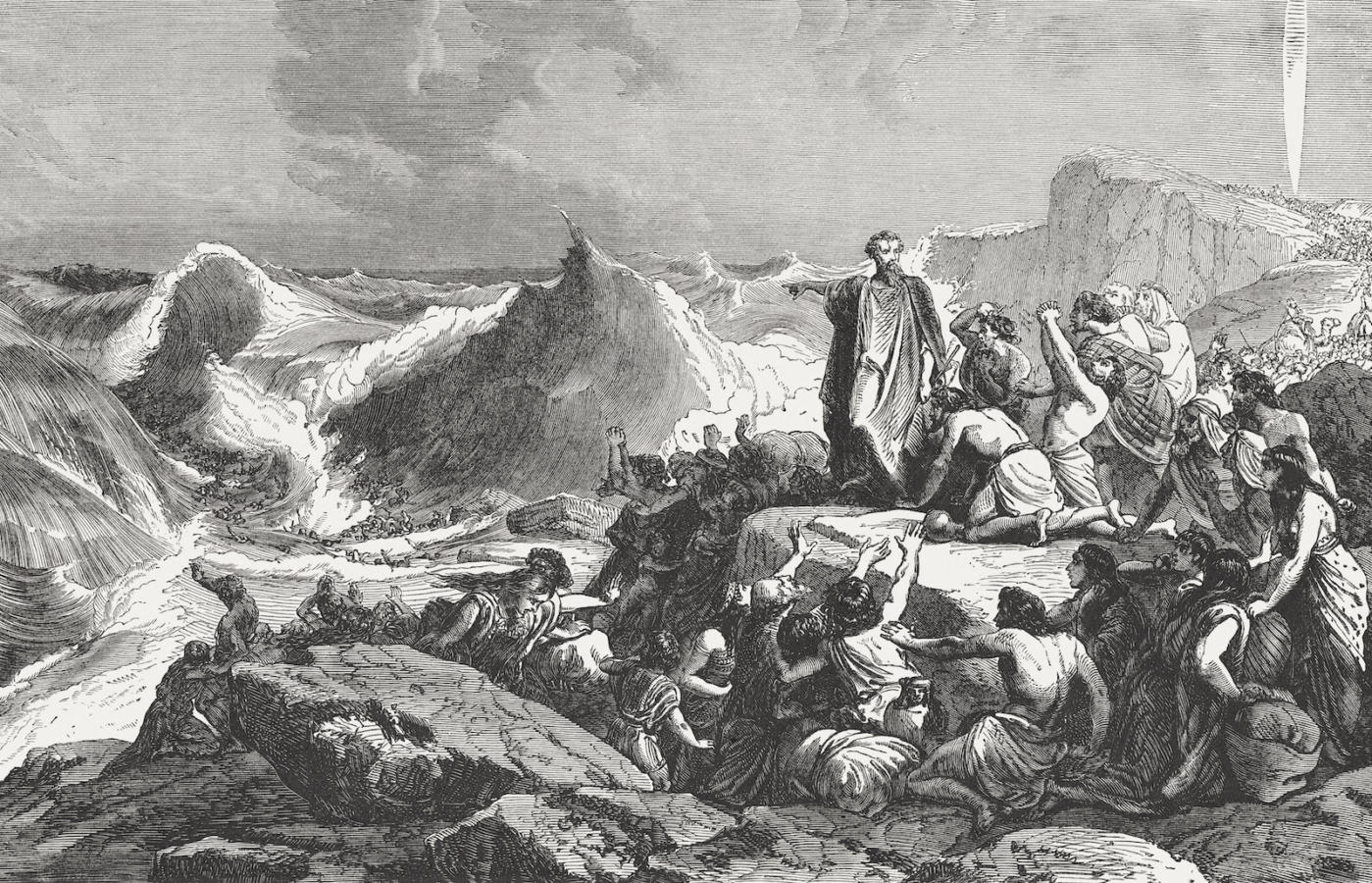

Few stories in human history have carried as much weight, meaning, and controversy as the Exodus—the biblical tale of the Israelites’ liberation from slavery in Egypt, their flight into the desert, and their eventual journey toward the Promised Land. For millennia, this narrative has shaped faith, identity, and culture. It has been retold in sacred scripture, sung in hymns, painted on cathedral walls, and reimagined in films that capture the drama of plagues, parted seas, and divine intervention.

But the question remains: Did the Exodus really happen? Was there truly a great departure of Hebrew slaves from Egypt, wandering in the wilderness for forty years before settling in Canaan? Or is the Exodus a myth—an epic story crafted by ancient writers to explain the origins of a people and their relationship with God?

Archaeology, the discipline that uncovers the physical traces of the past, has long been drawn into this debate. Over the past century, discoveries in Egypt, Sinai, and the Levant have provided tantalizing clues, sparking debates among scholars, theologians, and skeptics alike. The search for the historical Exodus is not merely about bricks and bones—it is about how humanity connects memory with material evidence, and myth with history.

The Biblical Narrative

Before turning to archaeology, it is important to revisit what the Bible actually says. The Book of Exodus describes the Israelites as slaves in Egypt, oppressed by a Pharaoh who feared their growing numbers. Through Moses, chosen by God, the people confront Pharaoh, culminating in a series of plagues that devastate the land. Eventually, Pharaoh relents, and the Israelites depart. Their escape is immortalized in the image of the Red Sea parting, allowing safe passage.

Following this miraculous deliverance, the Israelites wander the desert for forty years, guided by divine signs, before arriving at Mount Sinai, where they receive the Ten Commandments. The journey concludes with the conquest of Canaan, described in the subsequent biblical books of Joshua and Judges.

To millions, this is sacred history—a divine act of liberation. But for scholars, it raises pressing historical questions. When did this happen? Who were the Israelites at the time? And does archaeology bear any witness to such an event?

The Silence of the Egyptian Record

One of the first places scholars look for evidence is Egypt itself. If thousands of slaves suddenly fled, one might expect traces—administrative records, inscriptions, or references to upheaval. Yet, Egyptian records are silent about such an event.

The Pharaohs were meticulous chroniclers of their triumphs but rarely admitted defeats. If a large group of slaves escaped, it may have been seen as an embarrassment, unlikely to be recorded. Moreover, most Egyptian texts that survive are royal inscriptions or religious writings, not mundane administrative records. This makes the silence ambiguous: does it mean the Exodus never happened, or that it was simply not recorded?

Archaeologists have uncovered settlements in the Nile Delta region—especially Avaris (modern Tell el-Dab’a)—that show evidence of Semitic populations living in Egypt during the second millennium BCE. These people were not Egyptians but migrants from Canaan, speaking similar languages to the Israelites. Could the biblical Hebrews have been among them?

The Hyksos Connection

One possible historical parallel is the Hyksos, a group of Semitic rulers who controlled parts of Egypt between 1650–1550 BCE. Archaeological evidence shows they were eventually expelled by native Egyptian rulers. Their departure may have echoed in memory as a grand exodus. Some scholars propose that later generations of Israelites reinterpreted this event as their own story of liberation.

However, the Hyksos were not slaves—they were rulers. The biblical story emphasizes oppression and slavery, not kingship. Yet, memories of the Hyksos expulsion may have merged with tales of oppressed Semitic laborers, creating a composite tradition. In this way, history and myth could have intertwined.

The Life of Semitic Laborers in Egypt

Archaeology provides strong evidence that Semitic peoples lived in Egypt for centuries, particularly during the New Kingdom period (c. 1550–1070 BCE). Papyrus records mention foreign slaves working in construction, agriculture, and household service. Some were called ’Apiru or Habiru, terms that intriguingly resemble “Hebrew.”

These ’Apiru were not an ethnic group but rather a social class: displaced people, fugitives, mercenaries, or laborers. It is possible that the Israelites were part of this underclass, enduring harsh labor and longing for freedom. If some of them eventually escaped or migrated back toward Canaan, their experience may have grown into the foundational Exodus story.

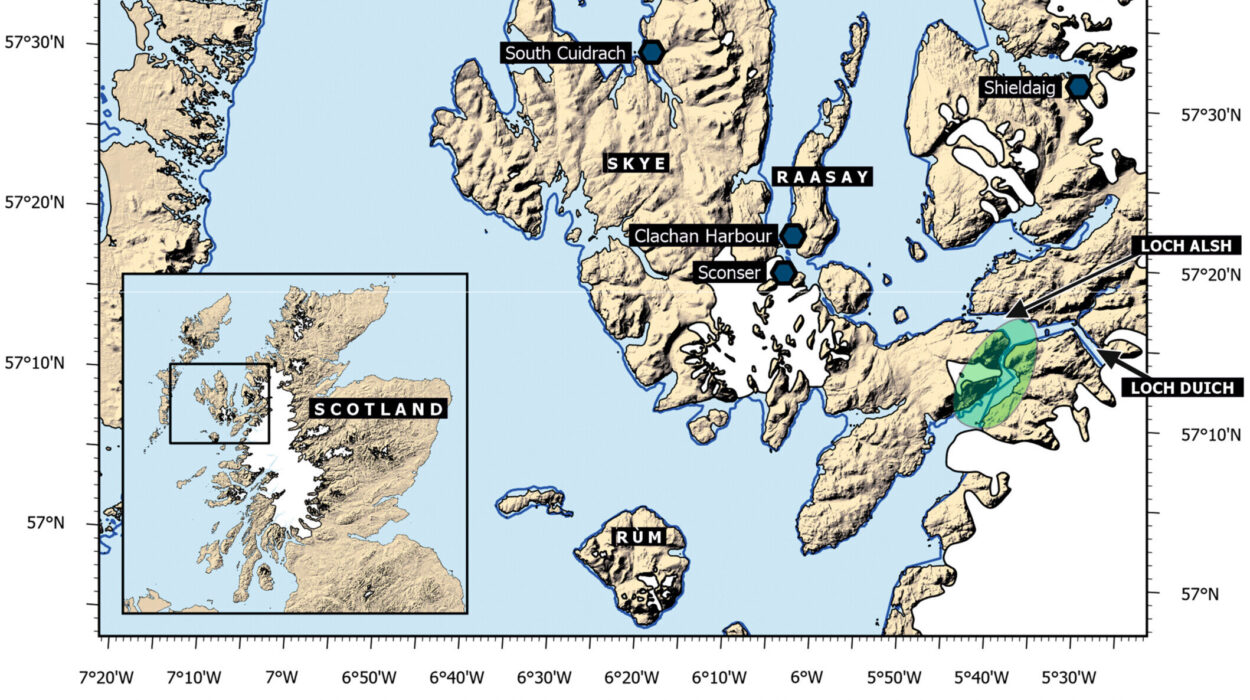

Tracing the Route: Sinai and the Wilderness

The Bible describes a dramatic escape through the wilderness, yet archaeology faces challenges in verifying this. Nomadic wanderings leave scant traces; temporary camps vanish without stone structures or pottery.

Extensive surveys of the Sinai Peninsula have revealed few signs of a massive migrating population in the Late Bronze Age (c. 1500–1200 BCE). If hundreds of thousands traveled there for forty years, one might expect more archaeological evidence—yet little has surfaced.

Some scholars argue that the numbers in Exodus are exaggerated. Instead of hundreds of thousands, the real group may have been much smaller—perhaps a few clans or families. A modest migration could have left little trace yet still formed the nucleus of a powerful national memory.

The Red Sea or the Reed Sea?

One of the most iconic moments in the Exodus is the parting of the Red Sea. Yet, the Hebrew term in the Bible—Yam Suph—may not mean “Red Sea” but “Sea of Reeds.” This suggests the crossing may have been through marshy lakes in the eastern Nile Delta, not the deep waters of the modern Red Sea.

Natural explanations have been proposed: strong winds, tides, or seismic activity could temporarily expose dry land, allowing passage before waters returned. Such an event, if experienced by escaping groups, could have been remembered as a miracle, amplified in storytelling across generations.

Canaan and the Rise of Israel

The end of the Exodus story places the Israelites in Canaan. Archaeology in this region reveals a complex picture. Around the 13th–12th centuries BCE, new small settlements appeared in the hill country of Canaan. These sites show continuity with local Canaanite culture but also signs of distinct practices—such as the avoidance of pig bones, aligning with later Israelite dietary laws.

This suggests that the Israelites emerged gradually from within Canaanite society rather than arriving as a massive conquering army from outside. Instead of a single dramatic exodus, the origins of Israel may have involved a fusion of local Canaanites with small groups of migrants, including possible escapees from Egypt. Over time, their collective memory shaped the Exodus as a defining story of identity.

Myth, Memory, and History

Whether or not the Exodus happened as described, it functions as a myth in the deepest sense: not a falsehood, but a narrative that carries profound truth. Myths give meaning, identity, and cohesion. The Exodus became the story of liberation—a God who sides with the oppressed, a people bound by covenant, and a journey toward freedom.

For generations of Jews, Christians, and Muslims, the Exodus has inspired struggles for justice, from the abolitionist movement to the civil rights era. Even without conclusive archaeological proof, the story’s power endures.

The Archaeological Debate

Scholars remain divided. Minimalists argue that the Exodus is largely a literary invention, written centuries after the supposed events, during the Babylonian exile in the 6th century BCE. They see it as a theological reflection, not historical memory.

Maximalists, on the other hand, argue that while the Bible embellishes, it preserves echoes of real experiences: the presence of Semites in Egypt, episodes of escape, and migration back to Canaan. They suggest that archaeology cannot disprove an event simply because it has not left abundant evidence.

Between these poles lies a middle view: the Exodus as a memory of smaller historical movements—perhaps groups of slaves or refugees—woven into a grand narrative that defined a people’s identity.

New Approaches: Interdisciplinary Insights

Recent studies have moved beyond traditional archaeology, incorporating climate science, linguistics, and even computer modeling. Some researchers link the timing of the Exodus to natural disasters, such as volcanic eruptions or climate shifts, that could have disrupted Egypt and enabled escape. Others study oral traditions, showing how memories evolve over centuries into foundational myths.

These approaches highlight that the Exodus is not merely about proving or disproving an event but about understanding how human communities preserve, transform, and retell their past.

Why the Exodus Matters Today

The search for the historical Exodus is more than an academic exercise. It reflects our yearning to connect with origins, to know where we come from and how stories shape who we are. The Exodus is not only about ancient Israelites; it is about the universal human desire for freedom, belonging, and hope.

Archaeology cannot provide a definitive answer—no single inscription or artifact has declared, “Here is the Exodus.” But archaeology does reveal the world in which such a story could emerge: a world of Semitic slaves in Egypt, migrations across deserts, and the gradual birth of new identities in Canaan.

In this way, the story of Exodus is both history and metaphor: history in the sense of reflecting real struggles of ancient peoples, and metaphor in its enduring call for liberation.

Conclusion: Between Sand and Story

So, was there a historical Exodus? The answer depends on how we define history. If we seek a literal replay of the biblical narrative, archaeology offers little confirmation. But if we ask whether experiences of migration, oppression, and deliverance shaped Israel’s origins, then archaeology and history affirm that such processes were real.

The Exodus may not have happened exactly as written, yet it lives on—not only in sacred texts but in the very identity of cultures and faiths. It remains a story that outlived its historical moment, transcending archaeology to speak to the human condition.

Every broken pot in the desert, every fragment of papyrus, every ancient settlement tells us this much: the line between myth and history is not a wall but a bridge. And across that bridge walks the Exodus—a story of people on the move, searching for freedom, and finding in their journey the birth of a nation.